Video games seem to be a unique type of digital activity. Empirically, the cognitive benefits of video games have support from multiple observational and experimental studies23,24,25. Their benefits to intelligence and school performance make intuitive sense and are aligned with theories of active learning and the power of deliberate practice26,27. There is also a parallel line of evidence from the literature on cognitive training intervention apps28,29, which can be considered a special (lab developed) category of video games and seem to challenge some of the same cognitive processes. Though, like for other digital activities, there are contradictory findings for video games, some with no effects30,31 and negative effects32,33.

The contradictions among studies on screen time and cognition are likely due to limitations of cross-sectional designs, relatively small sample sizes, and, most critically, failures to control for genetic predispositions and socio-economic context10. Although studies account for some confounding effects, very few have accounted for socioeconomic status and none have accounted for genetic effects. This matters because intelligence, educational attainment, and other cognitive abilities are all highly heritable9,34. If these genetic predispositions are not accounted for, they will confound the potential impact of screen time on the intelligence of children. For example, children with a certain genetic background might be more prone to watch TV and, independently, have learning issues. Their genetic background might also modify the impact over time of watching TV. Genetic differences are a major confounder in many psychological and social phenomena35,36, but until recently this has been hard to account for because single genetic variants have very small effects. Socioeconomic status (SES) could also be a strong moderator of screen time in children37. For example, children in lower SES might be in a less functional home environment that makes them more prone to watch TV as an escape strategy, and, independently, the less functional home environment creates learning issues. Although SES is commonly assumed to represent a purely environmental factor, half of the effect of SES on educational achievement is probably genetically mediated38,39—which emphasizes the need for genetically informed studies on screen time.

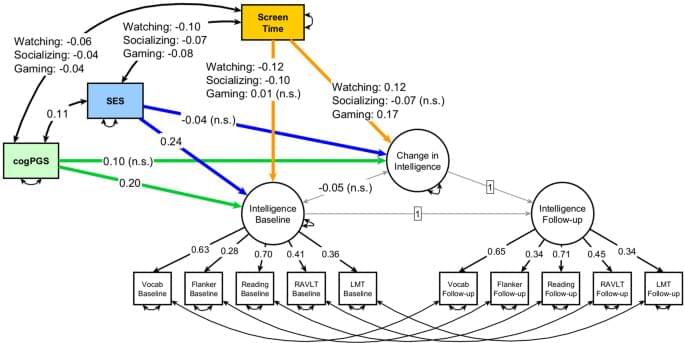

Here, we estimated the impact of different types of screen time on the change in the intelligence of children in a large, longitudinal sample, while accounting for the critical confounding influences of genetic and socioeconomic backgrounds. In specific, we had a strong expectation that time spent playing video games would have a positive effect on intelligence, and were interested in contrasting it against other screen time types. Our sample came from the ABCD study (http://abcdstudy.org) and consisted of 9,855 participants aged 9–10 years old at baseline and 5,169 of these followed up two years later.