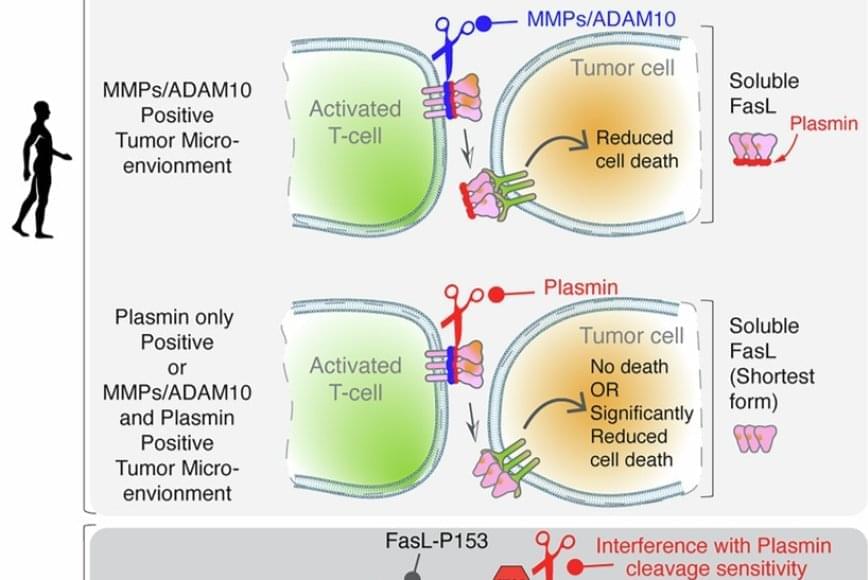

FasL is an immune cell membrane protein that triggers a programmed cell death called apoptosis. Activated immune cells, including CAR-T cells made from a patient’s immune system, use apoptosis to kill cancer cells.

The team discovered that in human genes, a single evolutionary amino acid change — serine instead of proline at position 153 — makes FasL more susceptible to being cut and inactivated by plasmin.

Plasmin is a protease enzyme that is often elevated in aggressive solid tumors like triple negative breast cancer, colon cancer and ovarian cancer.

This means that even when human immune cells are activated and ready to attack the tumor cells, one of their key death weapons — FasL — can be neutralized by the tumor environment, reducing the effectiveness of immunotherapies.

The findings may help explain why CAR-T and T-cell-based therapies can be effective in blood cancers but often fall short in solid tumors. Blood cancers often do not rely on plasmin to metastasize, whereas tumors like ovarian cancer rely heavily on plasmin to spread the cancer.

Significantly, the study also showed that blocking plasmin or shielding FasL from cleavage can restore its cancer-killing power. That finding may open new doors for improving cancer immunotherapy.