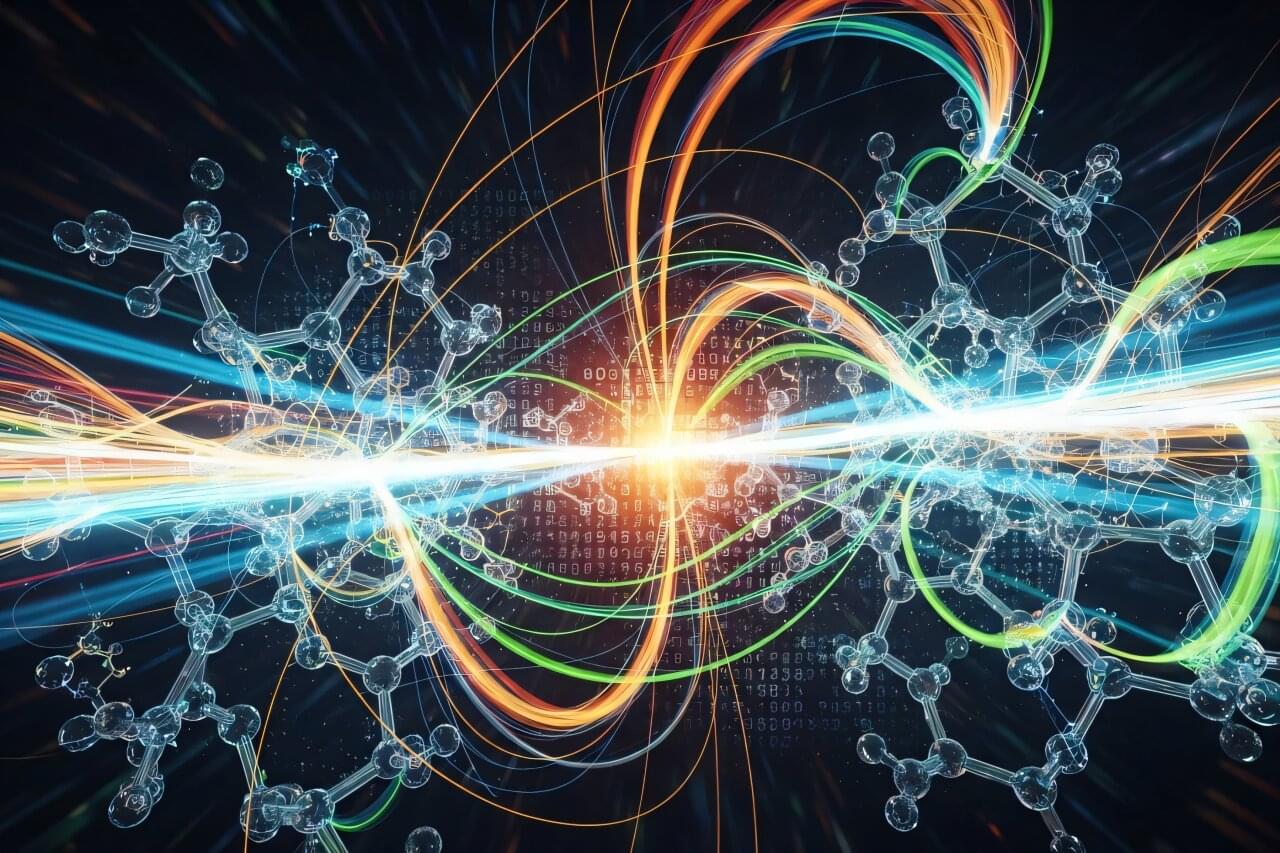

Lipid molecules, or fats, are crucial to all forms of life. Cells need lipids to build membranes, separate and organize biochemical reactions, store energy, and transmit information. Every cell can create thousands of different lipids, and when they are out of balance, metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases can arise. It is still not well understood how cells sort different types of lipids between cell organelles to maintain the composition of each membrane. A major reason is that lipids are difficult to study, since microscopy techniques to precisely trace their location inside cells have so far been missing.

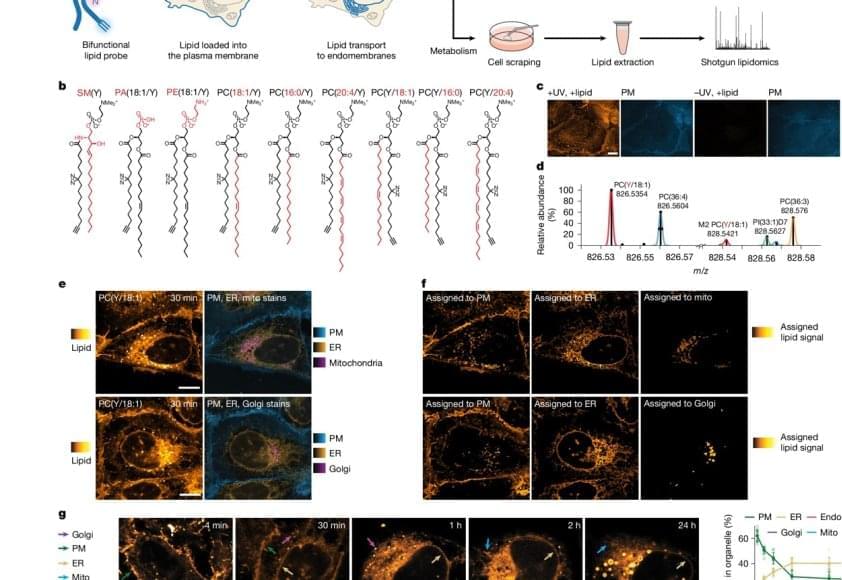

The researchers developed a method that enables visualizing lipids in cells using standard fluorescence microscopy. After the first successful proof of concept, the authors brought mass-spectrometry expert on board to study how lipids are transported between cellular organelles.

“We started our project with synthesizing a set of minimally modified lipids that represent the main lipids present in organelle membranes. These modified lipids are essentially the same as their native counterparts, with just a few different atoms that allowed us to track them under the microscope,” explains a PhD student in the group.

The modified lipids mimic natural lipids and are “bifunctional,” which means they can be activated by UV light, causing the lipid to bind or crosslink with nearby proteins. The modified lipids were loaded in the membrane of living cells and, over time, transported into the membranes of organelles. The researchers worked with human cells in cell culture, such as bone or intestinal cells, as they are ideal for imaging.

“After the treatment with UV light, we were able to monitor the lipids with fluorescence microscopy and capture their location over time. This gave us a comprehensive picture of lipid exchange between cell membrane and organelle membranes,” concludes the author.

In order to understand the microscopy data, the team needed a custom image analysis pipeline. “To address our specific needs, I developed an image analysis pipeline with automated image segmentation assisted by artificial intelligence to quantify the lipid flow through the cellular organelle system,” says another author.

By combining the image analysis with mathematical modeling, the research team discovered that between 85% and 95% of the lipid transport between the membranes of cell organelles is organized by carrier proteins that move the lipids, rather than by vesicles. This non-vesicular transport is much more specific with regard to individual lipid species and their sorting to the different organelles in the cell. The researchers also found that the lipid transport by proteins is ten times faster than by vesicles. These results imply that the lipid compositions of organelle membranes are primarily maintained through fast, species-specific, non-vesicular lipid transport.