Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

A full-scale prototype of the huge Starship rocket SpaceX says will fly people to the moon and Mars left the ground for the first time Tuesday in South Texas

A full-scale prototype of the huge Starship rocket SpaceX says will fly people to the moon and Mars left the ground for the first time Tuesday in South Texas, flying to an altitude of roughly 500 feet before settling on a nearby landing pad.

“Mars is looking real … Progress is accelerating,” says Elon Musk.

Mars 2020 Perseverance Rover How Many Different At This Time

Landing on Mars : February 2021

Specailty : Look for signs of past or present life and see if humans could one day explore Mars.

Deepfakes declared top AI threat, biometrics and content attribution scheme proposed to detect them

Biometrics may be the best way to protect society against the threat of deepfakes, but new solutions are being proposed by the Content Authority Initiative and the AI Foundation.

Deepfakes are the most serious criminal threat posed by artificial intelligence, according to a new report funded by the Dawes Centre for Future Crime at the University College London (UCL), among a list of the top 20 worries for criminal facilitation in the next 15 years.

The study is published in the journal Crime Science, and ranks the 20 AI-enabled crimes based on the harm they could cause.

Bruce Dorminey

Coming this week on Cosmic Controversy! I’m honored to welcome #Villanova University Professor Edward Guinan, an international expert on stellar astronomy and extrasolar planets, as my guest. We’ll be discussing the red supergiant star #Betelgeuse; our Sun over cosmic time; the mysterious star #Sirius; the North Star #Polaris; and, the potential for finding life around the Sun’s two nearest stellar neighbors. Stay tuned! brucedorminey.podbean.com

Scientists find vision relates to movement

To get a better look at the world around them, animals constantly are in motion. Primates and people use complex eye movements to focus their vision (as humans do when reading, for instance); birds, insects, and rodents do the same by moving their heads, and can even estimate distances that way. Yet how these movements play out in the elaborate circuitry of neurons that the brain uses to “see” is largely unknown. And it could be a potential problem area as scientists create artificial neural networks that mimic how vision works in self-driving cars.

To better understand the relationship between movement and vision, a team of Harvard researchers looked at what happens in one of the brain’s primary regions for analyzing imagery when animals are free to roam naturally. The results of the study, published Tuesday in the journal Neuron, suggest that image-processing circuits in the primary visual cortex not only are more active when animals move, but that they receive signals from a movement-controlling region of the brain that is independent from the region that processes what the animal is looking at. In fact, the researchers describe two sets of movement-related patterns in the visual cortex that are based on head motion and whether an animal is in the light or the dark.

The movement-related findings were unexpected, since vision tends to be thought of as a feed-forward computation system in which visual information enters through the retina and travels on neural circuits that operate on a one-way path, processing the information piece by piece. What the researchers saw here is more evidence that the visual system has many more feedback components where information can travel in opposite directions than had been thought.

Tesla Has Been Working On an RNA Bioreactor

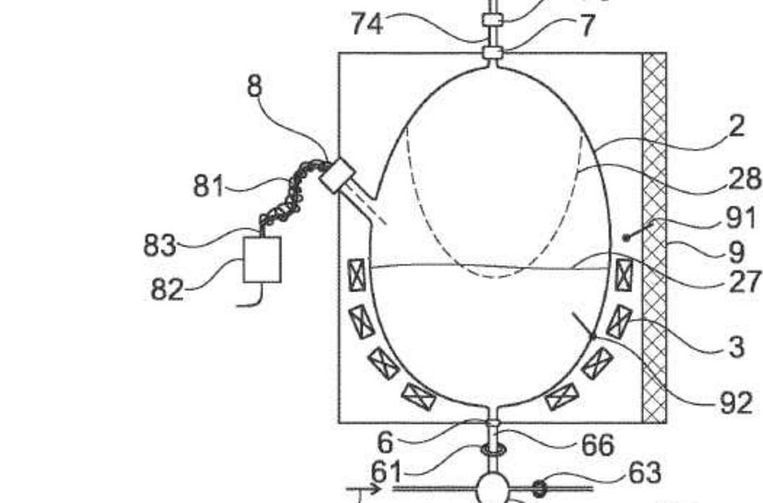

Tesla and CureVac have collaborated on a patent for an RNA bioreactor.

Although there are no human vaccines made with RNA, the technology could break through on COVID-19 (coronavirus).

The bioreactor works by combining chemical agents in an egg-shaped magnetic mixer.

Tesla has taken on the manufacturing role for a biotech startup with a revolutionary new RNA reactor concept. A tipster recently alerted Electrek to this year-old patent application, which lists both Tesla and German startup CureVac.

CureVac has made the news recently because of a misinformed factoid that it was being purchased by President Donald Trump. That’s partly because CureVac is working on the groundwork for a COVID-19 (coronavirus) vaccine. Today, the European Investment Bank (EIB) reported that it’s awarded an $84 million loan to CureVac to accelerate that vaccine development process.

Lower Education Levels May Decrease Survival in Multiple Myeloma

A study published in BMC Cancer analyzed the relationship between education level and survival in multiple myeloma and observed that patients with lower education levels may have lower survival rates.

A study observed that multiple myeloma patients with lower education levels may have lower survival rates compared to those with higher education levels.

Amazing footage of the Starship SN5 prototype making a 150-meter hop

The footage of the tiny tiny landing legs deploying is particularly fantastic. Credit: SpaceX