Circa 2017

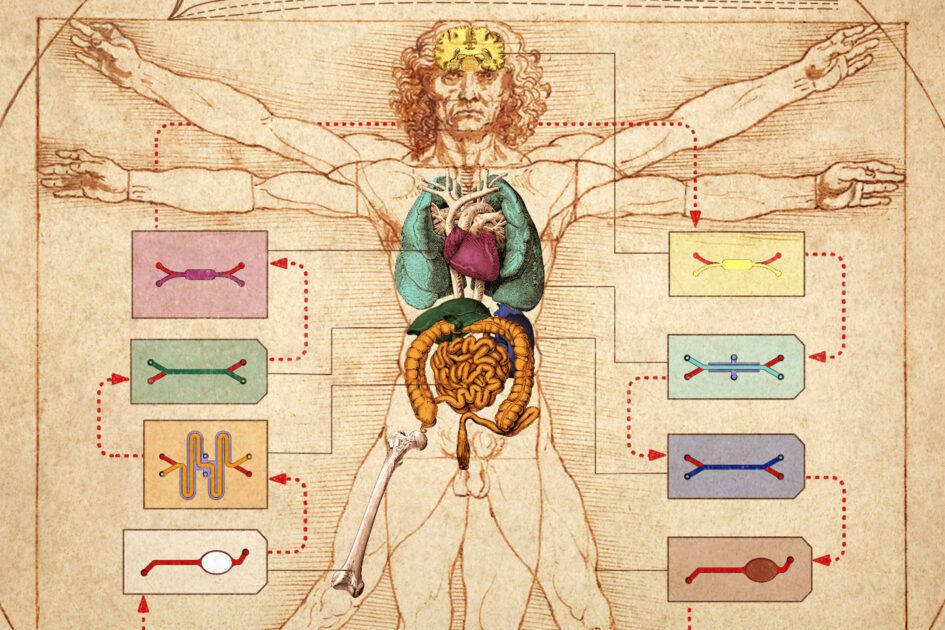

Positron emission tomography (PET) image synthesis plays an important role, which can be used to boost the training data for computer aided diagnosis systems. However, existing image synthesis methods have problems in synthesizing the low resolution PET images. To address these limitations, we propose multi-channel generative adversarial networks (M-GAN) based PET image synthesis method. Different to the existing methods which rely on using low-level features, the proposed M-GAN is capable to represent the features in a high-level of semantic based on the adversarial learning concept. In addition, M-GAN enables to take the input from the annotation (label) to synthesize the high uptake regions e.g., tumors and from the computed tomography (CT) images to constrain the appearance consistency and output the synthetic PET images directly.