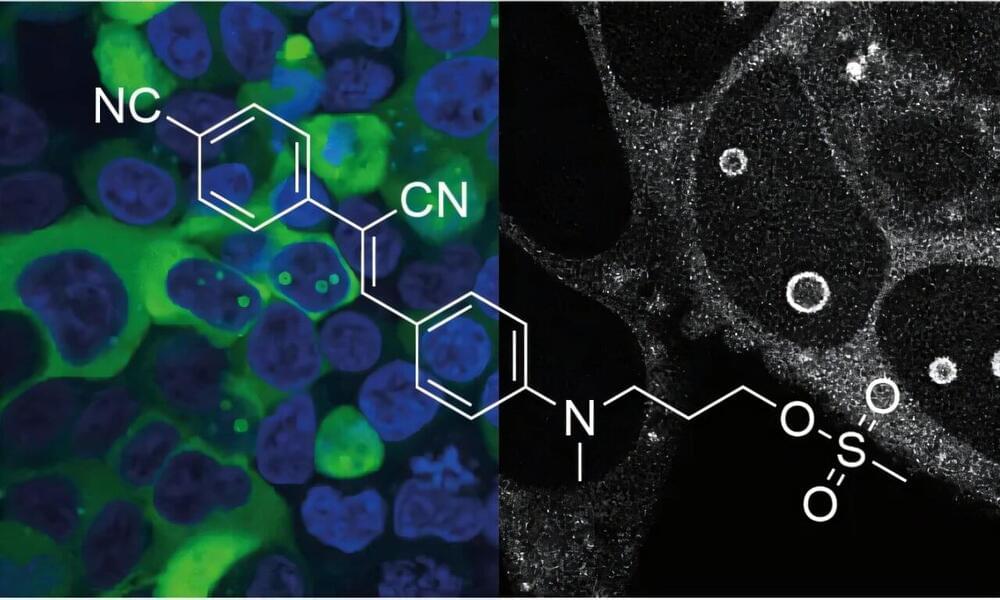

The specific labeling of RNA in living cells poses many challenges. In a new article published in the journal Nature Chemical Biology, researchers from the University of Innsbruck describe a structure-guided approach to the formation of covalent (i.e., irreversibly tethered) RNA-ligand complexes.

The key to this is the modification of the original ligand with a reactive “handle” that allows it to react with a nucleobase at the RNA binding site. This was first demonstrated in vitro and in vivo using the example of an RNA riboswitch.

The versatility of the approach is highlighted by the first covalent “fluorescent light-up RNA aptamer” (coFLAP). This system retains its strong fluorescence during imaging in living cells even after washing, can be used for high-resolution microscopy and is particularly suitable for FRAP (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching) for monitoring intracellular RNA dynamics.