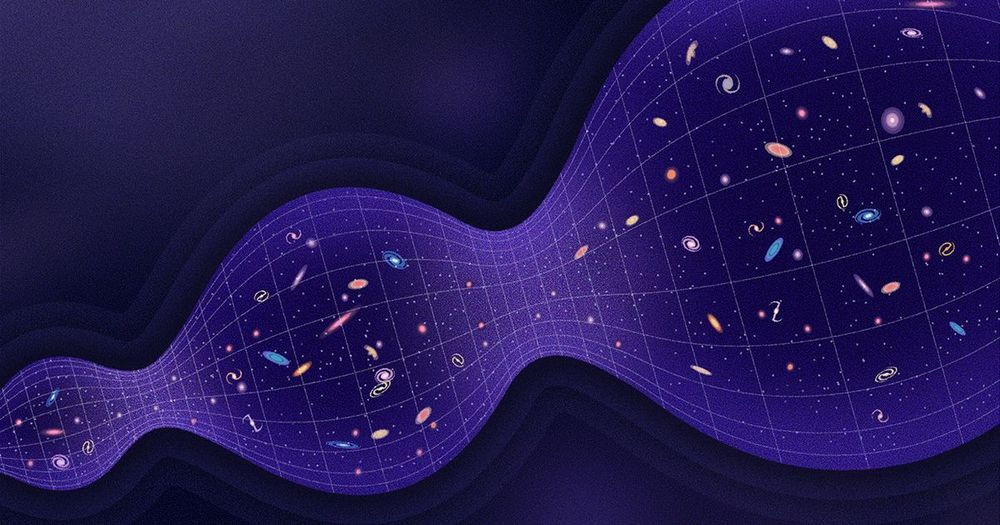

Detailed computer simulations have found that a cosmic contraction can generate features of the universe that we observe today.

In COVID-19, the sense of smell can diminish, vanish, or oddly skew, for weeks or months. The loss usually starts suddenly and is more than the temporarily dulled chemical senses of a stuffy nose from the common cold. As researchers followed up mounting reports of loss of olfaction, a surprising source of perhaps the longest-lasting cases emerged: stem cells in the olfactory epithelium.

A Common Symptom

Facebook groups may be ahead of the medical literature in providing vivid descriptions of the loss of olfaction as people swap advice and compare how long they’ve been unable to smell. The experiences can be bizarre, but at the same time, shared.

Circa 2006

Aiming to create a miniature motor capable of 1 million revolutions per minute, electronics researchers at ETH Life in Zurich are half-way to their goal.

The gas turbine-powered device produces force equivalent to 100 watts and is 95 percent fuel efficient, and gets 10 hours of operation out of the tank.

In December 2019, Donald Trump signed the U.S. Space Force Act, peeling off an orbit-and-beyond branch of the military, much as the Air Force grew out of the Army in the 1940s.

For now, the Space Force still resides within the Air Force, but nearly 90 of this year’s approximately 1000 Air Force Academy graduates became the first officers commissioned straight into the new organization. Some of those graduates were members of an academy group called the Institute for Applied Space Policy and Strategy (IASPS). Featuring weekly speakers and formalized research projects the students hope to turn into peer-reviewed papers, the group aims to game out the policies and philosophies that could guide military space activity when they are old enough to be in charge. In particular, these young cadets are interested in whether the Space Force might someday have a military presence on the Moon, and how it might work with civilians.

That activity could put the Space Force in conflict with scientists, who typically view the cosmos as a peaceful place for inquiry. But part of the club’s mission is speculating about that interplay—between the military and civilian scientists, civil space agencies, and private companies. Cadet J. P. Byrne, who will graduate in 2021, is the group’s current president. He chatted with ScienceInsider about the institute’s work. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What does IASPS hope to accomplish?

A: Our main goal is to develop space-minded cadets not just for the Air Force, but also for the Space Force. It’s really important to know how space works, and we like to think we drive the conversation for space information in an unclassified setting.

Q: What, as an Air Force Academy cadet, interests you about space?

A: I actually wanted to be a pilot originally. But going into my junior year, seeing all the developments, I started really enjoying space. You hear this idea of a “new space era” a lot. When I think about that, it reminds me of the early excitement about the powered aircraft of the early 20th century, in that we get to explore ideas that haven’t been thought of yet. A lot of people say it’s human destiny to explore space. To me, it’s more adventuring into the unknown, or at least the less known.

Swarm intelligence (SI) is concerned with the collective behaviour that emerges from decentralised self-organising systems, whilst swarm robotics (SR) is an approach to the self-coordination of large numbers of simple robots which emerged as the application of SI to multi-robot systems. Given the increasing severity and frequency of occurrence of wildfires and the hazardous nature of fighting their propagation, the use of disposable inexpensive robots in place of humans is of special interest. This paper demonstrates the feasibility and potential of employing SR to fight fires autonomously, with a focus on the self-coordination mechanisms for the desired firefighting behaviour to emerge. Thus, an efficient physics-based model of fire propagation and a self-organisation algorithm for swarms of firefighting drones are developed and coupled, with the collaborative behaviour based on a particle swarm algorithm adapted to individuals operating within physical dynamic environments of high severity and frequency of change. Numerical experiments demonstrate that the proposed self-organising system is effective, scalable and fault-tolerant, comprising a promising approach to dealing with the suppression of wildfires – one of the world’s most pressing challenges of our time.

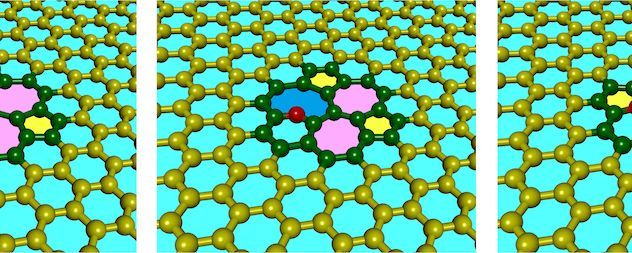

Graphene and other carbon materials are known to change their structure and even self-heal defects, but the processes involved in these atomic rearrangements often have high energy barriers and so shouldn’t occur under normal conditions. An international team of researchers in Korea, the UK, Japan, the US and France has now cleared up the mystery by showing that fast-moving carbon atoms catalyse many of the restructuring processes.

Graphene – a carbon sheet just one atomic layer thick – is an ideal system for studying defects because of its simple two-dimensional single-element structure. Until now, researchers typically explained the structural evolution of graphene defects via a mechanism known as a Stone-Thrower-Wales type bond rotation. This mechanism involves a change in the connectivity of atoms within the lattice, but it has a relatively large activation energy, making it “forbidden” without some form of assistance.

Using some of the best transmission electron microscopes available, researchers led by Alex Robertson of Oxford University and Kazu Suenaga of AIST Tsukuba found that so-called “mediator atoms” – carbon atoms that do not fit properly into the graphene lattice – act as catalysts to help bonds break and form. “The importance of these rapid, unseen ‘helpers’ has been previously underestimated because they move so fast and have been next-to-impossible to observe,” says co-team leader Christopher Ewels, a nanoscientist at the University of Nantes.

Imagine tiny crystals that “blink” like fireflies and can convert carbon dioxide, a key cause of climate change, into fuels.

A Rutgers-led team has created ultra-small titanium dioxide crystals that exhibit unusual “blinking” behavior and may help to produce methane and other fuels, according to a study in the journal Angewandte Chemie. The crystals, also known as nanoparticles, stay charged for a long time and could benefit efforts to develop quantum computers.

“Our findings are quite important and intriguing in a number of ways, and more research is needed to understand how these exotic crystals work and to fulfill their potential,” said senior author Tewodros (Teddy) Asefa, a professor in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers University-New Brunswick. He’s also a professor in the Department of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering in the School of Engineering.

Circa 2015

A nighttime shot shows some of the antennas of the Owens Valley Long Wavelength Array in California, with the center of our galaxy in the background. (Credit: Gregg Hallinan)

The Owens Valley Long Wavelength Array (OV-LWA) is already producing unprecedented videos of the radio sky. Astronomers hope that it will help them piece together a more complete picture of the early universe and learn about extrasolar space weather—the interaction between nearby stars and their orbiting planets.

Victims included Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, former President Barack Obama and Tesla CEO Elon Musk. Accounts for those people, and others, posted tweets asking followers to send bitcoin to a specific anonymous address.

For their efforts, the scammers received over 400 payments in bitcoin, with a total value of $121,000 at Thursday’s exchange rate, according to an analysis of the Bitcoin blockchain performed by Elliptic, a cryptocurrency compliance firm.

Elliptic co-founder Tom Robinson said it’s a low sum for what appears to be a historic hack that Twitter said involved an insider.

According to Forbes, payroll costs consume up to 25 per cent of a restaurant’s profit. Restaurateurs in Sydney and other parts of Australia hope to combat that expense by following in the footsteps of venues in Asia that have used drone waiters instead of human wait staff.

Faster and Human-Free Waiter drones are robotic devices that soar through the air with platters of food and glasses of beverages perched on top. Customers place their orders via electronic devices or other means, then the kitchen sends out their food on trays carried by machines rather than humans. Each drone can carry up to 4.4 pounds of cargo.

Sensors on the sides of the drones prevent them from crashing into objects or people as they navigate busy restaurants. While this strategy eliminates the human element that many experts believe is essential to the hospitality industry, the waiter drones’ success in Asia suggests they might prove a valuable contribution to restaurants in Australia.