A doomsday fungus known as Bd has condemned more species to extinction than any other pathogen.

Arthritis is usually painful. So is the surgery to fix it, at least in the immediate aftermath. So when a 66-year old woman at Raigmore Hospital in Inverness, Scotland, told doctors that her severely arthritic hand felt fine both before and after her operation, they were suspicious. The joint of her thumb was so severely deteriorated that she could hardly use it—how could that not hurt?

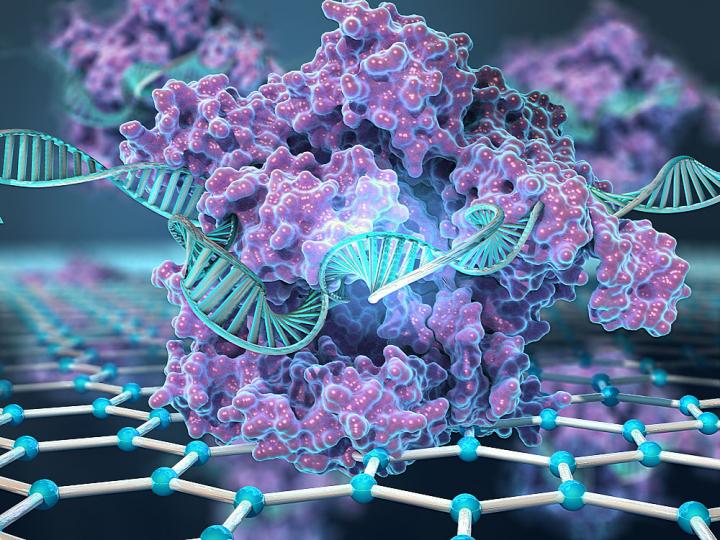

So they sent her to see teams specializing in pain genetics at University College London and the University of Oxford. Those researchers took DNA samples from both her and some of her family members and uncovered her secret: a tiny mutation in a newly-discovered gene. They recently published their results in the British Journal of Anaesthesia.

This minuscule deletion is inside something called a pseudogene, which is a partial copy of a fully functioning gene inserted elsewhere in the genome. Pseudogenes don’t always have a function—sometimes they’re just junk DNA—but some of them have residual functionality leftover from the original gene’s purpose.

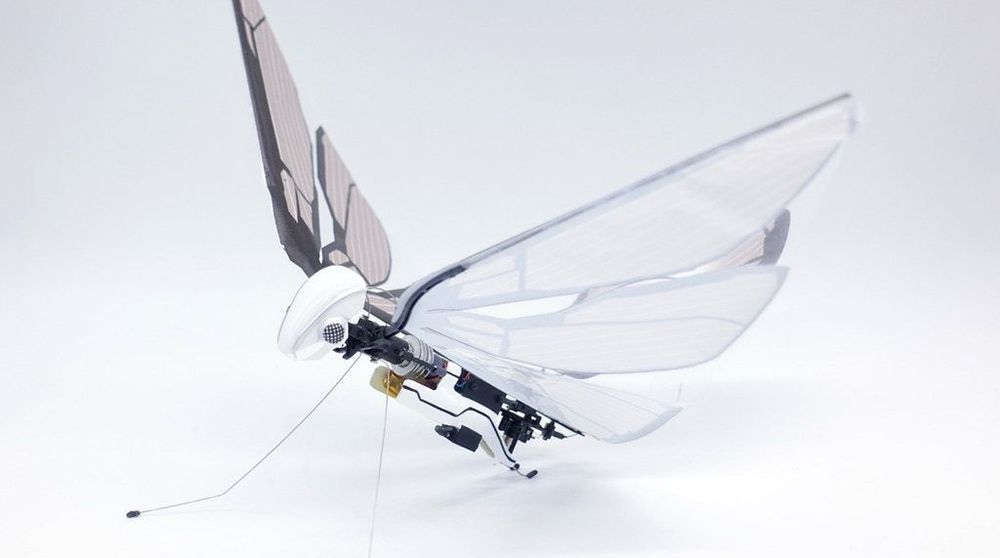

Aeronautical engineer Edwin Van Ruymbeke has developed a remote-controlled insect ornithopter called MetaFly.

Capable of reaching a top speed of 18 km/h (11 mph) and a maximum range of 100 metres (328 ft), the wings are flapped using a mechanical coreless motor and an aluminum heat sink that is powered by a rechargeable lithium-polymer battery.

Weighing 10 grams (0.35 oz), MetaFly measures 19 cm long (7.5 in) with a 29-cm (11.4-in) wingspan. The patented wings are made from carbon fibre, liquid crystal polymer and oriented polypropylene.

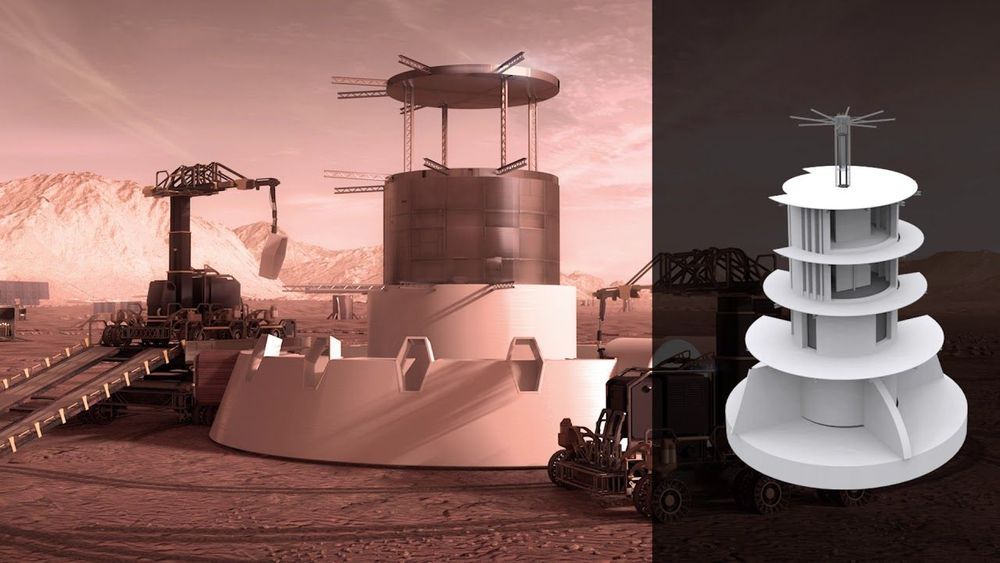

It’s a fascinating competition that paints an incredibly detailed picture of what the future of Moon or even Mars exploration could look like one day — and we’ve never been closer to that future.

READ MORE: Top Three Teams Share $100,000 Prize in Complete Virtual Construction Level of 3D-Printed Habitat Challenge [NASA]

More on the Challenge: Here Are The Finalists For NASA’s Mars Habitat Design Competition.

The city of the future is a symbol of progress. The sci-fi vision of the future city with sleek skyscrapers and flying cars, however, has given way to a more plausible, human, practical, and green vision of tomorrow’s smart city. Whilst smart city visions differ, at their heart is the notion that in the coming decades, the planet’s most heavily concentrated populations will occupy city environments where a digital blanket of sensors, devices and cloud connected data is being weaved together to build and enhance the city living experience for all. In this context, smart architecture must encompass all the key elements of what enable city ecosystems to function effectively. This encompasses everything from the design of infrastructure, workspaces, leisure, retail, and domestic homes to traffic control, environmental protection, and the management of energy, sanitation, healthcare, security, and a building’s eco-footprint.

The

Livingston is sitting comfortably in his office in Portland, Oregon, when he appears on the screens inside the car and announces he’ll be our teleoperator this afternoon. A moment later, the MKZ pulls into traffic, responding not to the man in the driver’s seat, but to Livingston, who’s sitting in front of a bank of screens displaying feeds from the four cameras on the car’s roof, working the kind of steering wheel and pedals serious players use for games like Forza Motorsport. Livingston is a software engineer for Designated Driver, a new company that’s getting into teleoperations, the official name for remotely controlling self- driving vehicles.

Designated Driver is just the latest competitor to enter the market for the teleoperation tech that will make robo-cars work.