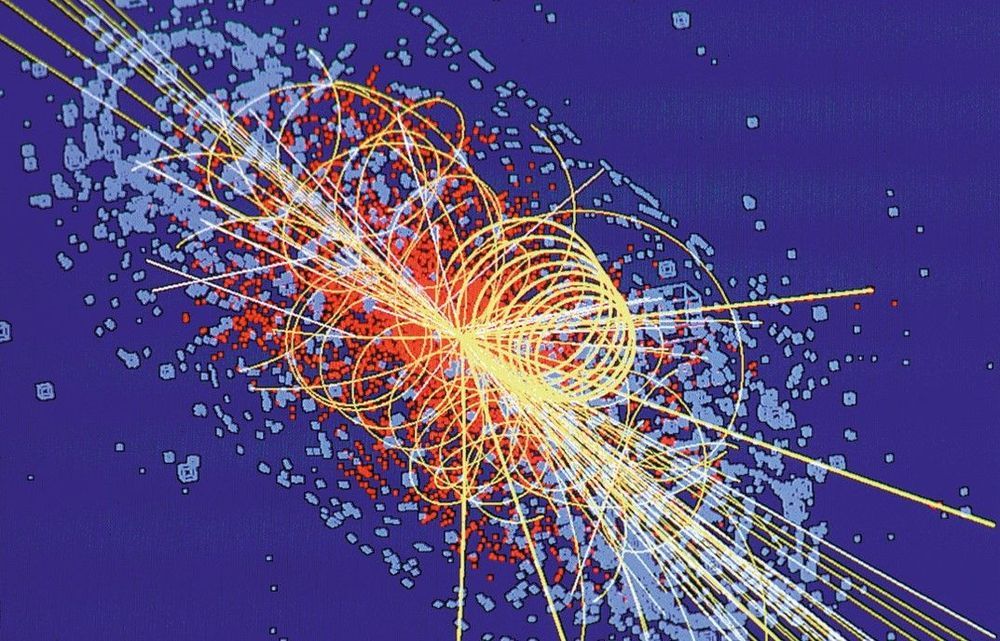

IBM quantum computer runs machine-learning algorithm to find Higgs events.

Coronavirus is sending in the drones. In what’s being billed as a “world first,” startup Manna Aero has begun a drone delivery service in Moneygall, Ireland. Delivering medicine to vulnerable people locked in their homes, it provides yet another strong example of how technology is helping the world adjust to life in the shadow of the coronavirus.

Having received authorisation from the Irish Aviation Authority, Manna Aero’s service began last Friday as a pilot in Moneygall, which was previously best known as Barack Obama’s ancestral village. However, if the trial is successful, the service will be rolled out throughout Ireland, and could also be used to deliver food.

The drones will deliver prescription orders for medicine to around a dozen households. As Manna Zero’s founder Bobby Healy told the Irish Independent, the drones ensure “zero human-contact” and can execute deliveries “in ways normal delivery can’t.”

Shortly after the failure, SpaceX’s founder and chief engineer, Elon Musk, said on Twitter, “We will see what data review says in the morning, but this may have been a test configuration mistake.” A testing issue would be good in the sense that it means the vehicle itself performed well, and the problem can be more easily addressed.

This is the third time a Starship has failed during these proof tests that precede engine tests and, potentially flight tests. Multiple sources indicated that had these preliminary tests succeeded, SN3 would have attempted a 150-meter flight test as early as next Tuesday.

Here’s a recap of SpaceX’s efforts to test full-size Starships to date:

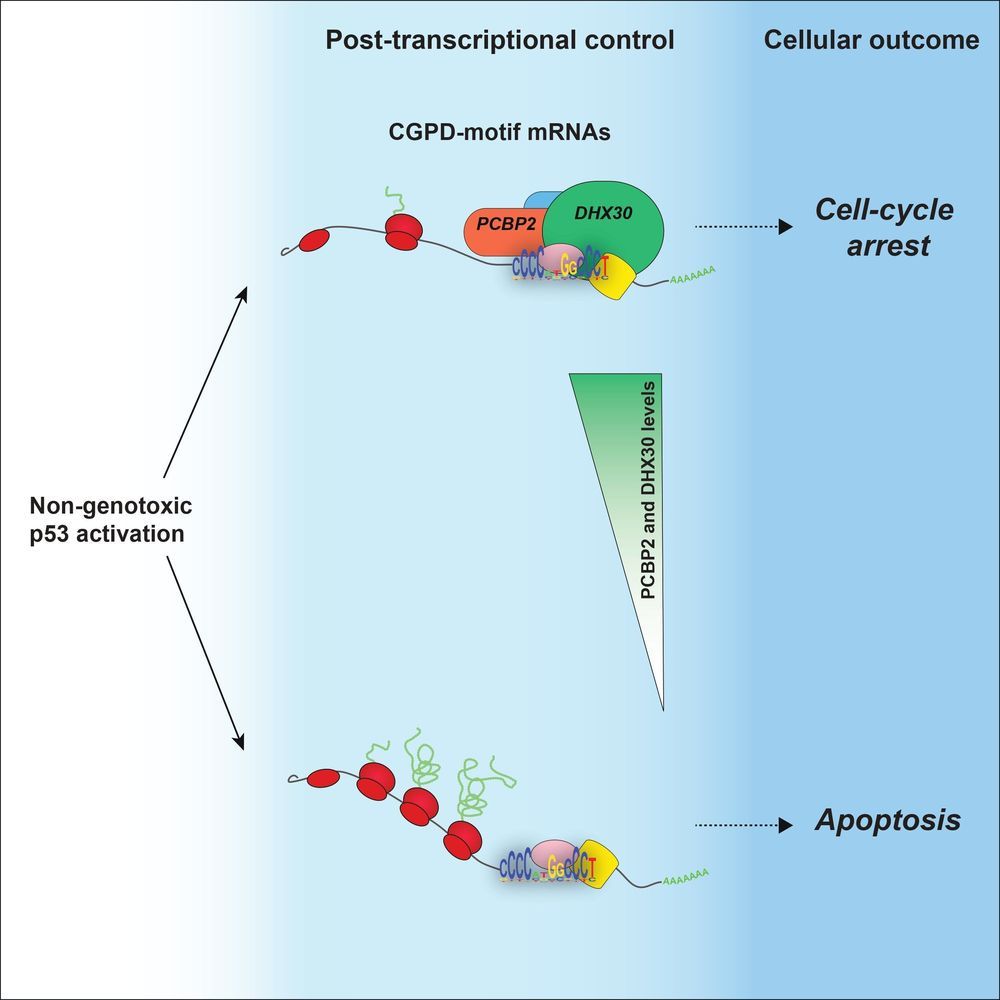

There is an ongoing battle between cancer cells and p53, the protein known as “the guardian of the genome,” and a study conducted at the University of Trento has identified a number of factors that influence the outcome of this battle and therefore the effectiveness of cancer treatments.

Scientists explore two therapeutic cancer treatment scenarios: In one scenario, cancer cells stop proliferating; in the other, their death rate increases. Both of these outcomes are regulated the protein p53. Based on the new findings, a specific factor, a protein known as DHX30, determines how p53 can lead cancer cells to their death. That is the conclusion reached by a team of researchers of the University of Trento, who focused on a new molecular mechanism that works like a switch.

Erik Dassi, member of the research team, said, “When cancer cells are treated with a certain drug, it is the action of this switch (DHX30) that makes them to go toward cell death and not in the direction of cell cycle arrest.”

A new study suggests that the enzyme intestinal alkaline phosphatase (IAP) appears to help to prevent age-related loss of intestinal barrier integrity in mice, fruit flies, and potentially humans.

Improving intestinal barrier integrity

There can now be little doubt that the decline of intestinal barrier integrity and the resulting inflammation play an important role in aging. In fact, some researchers suggest that inflammaging, the low-grade chronic background of inflammation seen in older people, has its origin point in the microbiome, the ecosystem of bacteria living in our guts.

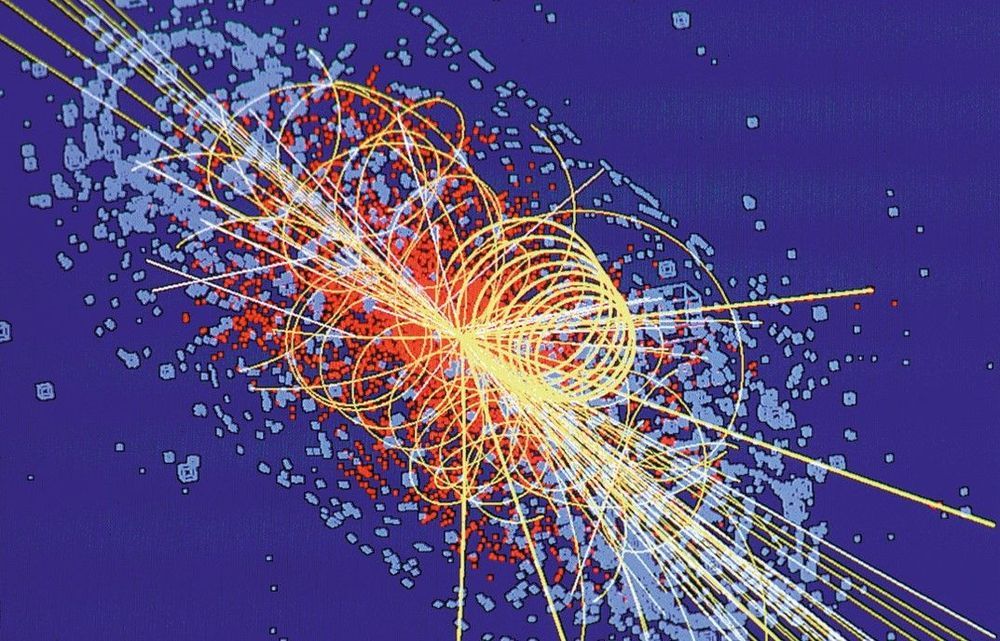

Brain implants are neural implants that are used to stimulate the parts & structures of the nervous system. These implants are technical systems that communicate with the nervous system and help to enhance senses, physical movement, and memory after a stroke or other head injuries. Deep brain stimulation and spinal cord stimulation are used to treat depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder and epilepsy, among other neural disorders.

Technology has touched all aspects of our lives in this 21st century world that we live in and has, in fact, become an integral part of our lives. So much so that we start feeling incomplete as soon as we manage to get away from it.

No doubt, it has enhanced our lives in many different ways and today we can do things that we couldn’t have even imagined a few decades ago. I mean, sending a text to someone half way around the world in an instant? Almost feels like magic, doesn’t it?

🤦🏻♂️🤦🏻♂️🤦🏻♂️

CONSPIRACY nuts are reportedly setting phone masts alight and targeting engineers after a bizarre claim 5G “radiation” caused the deadly coronavirus spread.

The theory originated last month after a video filmed at a US health conference claimed Africa was not as affected by the disease because it is “not a 5G region”.

The myth was quickly debunked after the World Health Organisation confirmed there were thousands of Covid-19 cases in Africa.