Malicious PyPI packages, repo hijacks, and CVEs in Python containers put devs at risk. Learn how to stay secure.

Researchers at European XFEL in Germany have tracked in real time the movement of individual atoms during a chemical reaction in the gas phase. Using extremely short X-ray flashes, they were able to observe the formation of an iodine molecule (I₂) after irradiating diiodomethane (CH₂I₂) molecules by infrared light, which involves breaking two bonds and forming a new one.

At the same time, they were able to distinguish this reaction from two other reaction pathways, namely the separation of a single iodine atom from the diiodomethane, or the excitation of bending vibrations in the bound molecule. The results, published in Nature Communications, provide new insights into fundamental reaction mechanisms that have so far been very difficult to distinguish experimentally.

So-called elimination reactions in which small molecules are formed from a larger molecule are central to many chemical processes—from atmospheric chemistry to catalyst research. However, the detailed mechanism of many reactions, in which several atoms break and re-form their bonds, often remains obscure. The reason: The processes take place in incredibly short times—in femtoseconds, or a few millionths of a billionth of a second.

Scientists at Johns Hopkins have grown a first-of-its-kind organoid mimicking an entire human brain, complete with rudimentary blood vessels and neural activity. This new “multi-region brain organoid” connects different brain parts, producing electrical signals and simulating early brain development. By watching these mini-brains evolve, researchers hope to uncover how conditions like autism or schizophrenia arise, and even test treatments in ways never before possible with animal models.

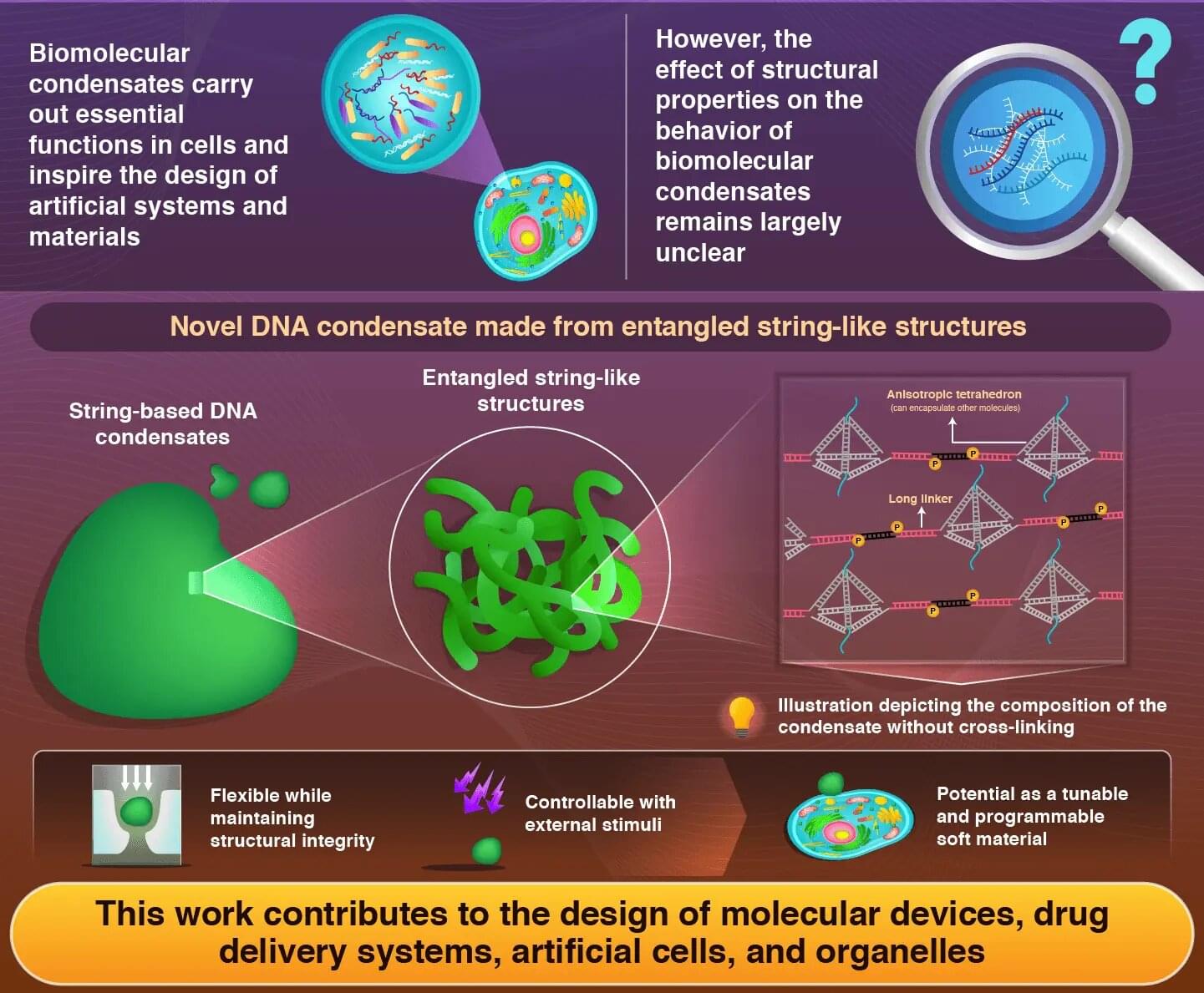

Newly developed DNA nanostructures can form flexible, fluid, and stimuli-responsive condensates without relying on chemical cross-linking, report researchers from the Institute of Science Tokyo and Chuo University, in the journal JACS Au.

Owing to a rigid tetrahedral motif that binds the linkers in a specific direction, the resulting string-like structures form condensates with exceptional fluidity and stability. These findings pave the way for adaptive soft materials with potential applications in drug delivery, artificial organelles, and bioengineering platforms.

Within living cells, certain biomolecules can organize themselves into specialized compartments called biomolecular condensates. These droplet-like structures play crucial roles in cellular functions, such as regulating gene expression and biochemical reactions; they essentially represent nature’s clever way of organizing cellular activity without the need for rigid membranes.