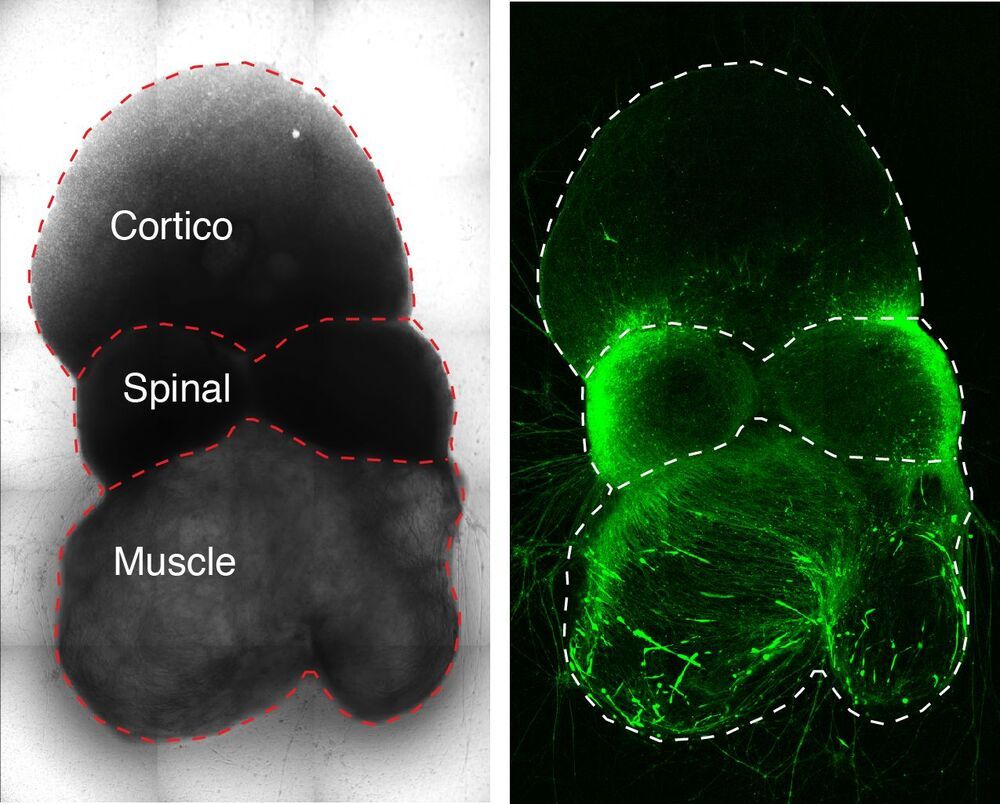

A Stanford Medicine team used human stem cells to assemble a working nerve circuit connecting brain tissue to muscle tissue. The research could enable scientists to better understand neurological disorders that affect movement.

Over the past 25 years, suicide attacks have emerged as a method used on a large scale by terrorist organizations to inflict lethal damage and create fear and chaos. Data collected by the University of Chicago’s Project on Security & Threats shows that worldwide there were 5, 021 suicide attacks utilizing bombs, which resulted in 47, 253 deaths and 113, 413 wounded from 2000 to 2016.

And recent news reports have highlighted the attempted use of suicide bombs in U.S. subways and city streets as well as on major airlines. An individual willing to sacrifice their own life in an attack is a significant force-multiplier, who too often escapes conventional threat detection methods. However, new technologies may yet close the security gap.

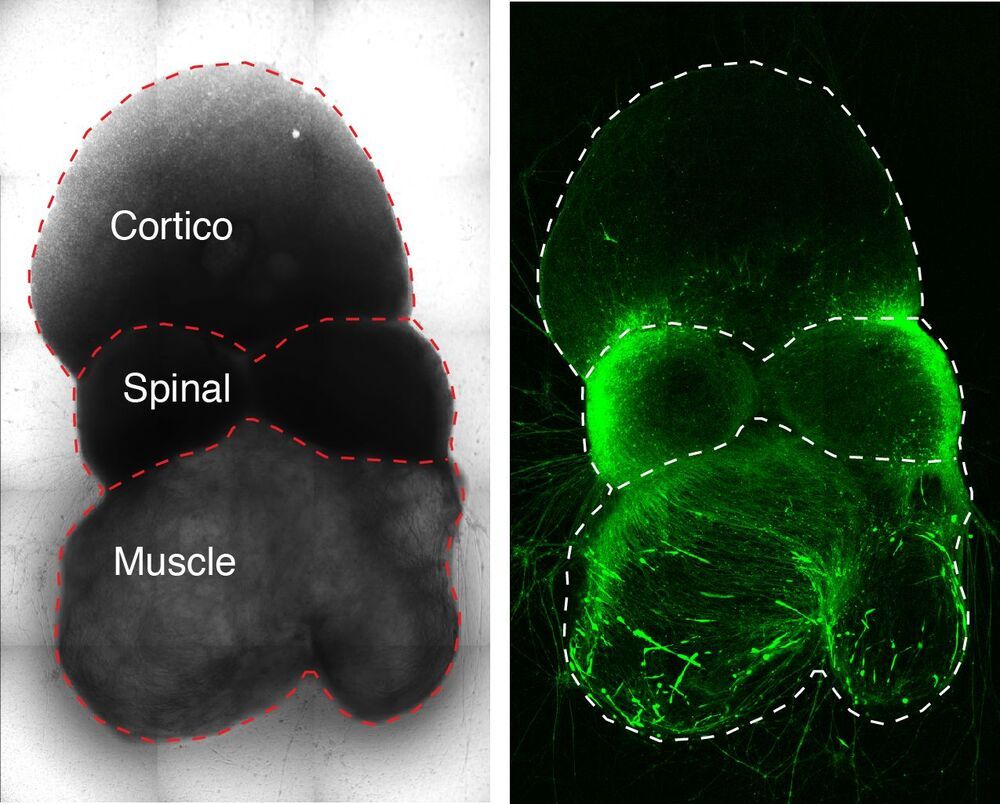

To detect suicide bombers preparing to attack public places and other high-value targets, a research team led by a professor at the Naval Postgraduate School invented a method to detect persons wearing wires or a significant amount of metal that might be part of an explosive device.

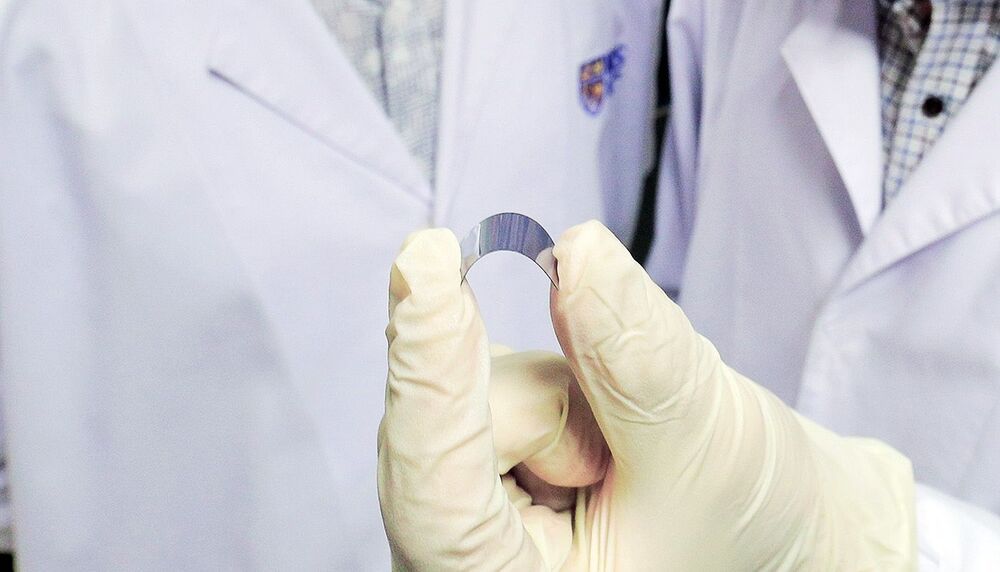

A video uploaded by the CSAIL team shows off the system. The drone pilot is able to maneuver a small drone through a series of rings easily just by twisting, raising, and lowering his forearm thanks to a device strapped around his arm.

The goal is to make controlling the drone — and potentially other pieces of technology — as natural as possible by harnessing human intuition.

A paper published last month details the such a “plug-and-play gesture control” that relies on muscle and motion sensors.

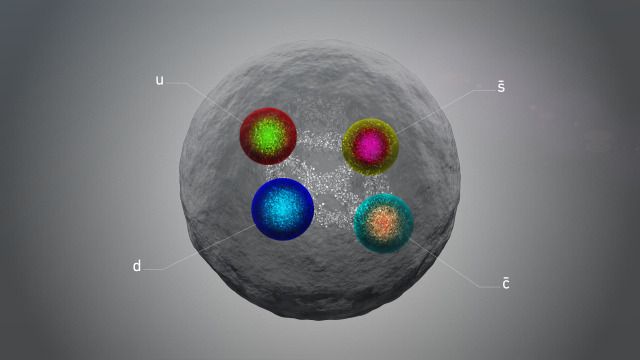

The LHCb experiment at CERN has developed a penchant for finding exotic combinations of quarks, the elementary particles that come together to give us composite particles such as the more familiar proton and neutron. In particular, LHCb has observed several tetraquarks, which, as the name suggests, are made of four quarks (or rather two quarks and two antiquarks). Observing these unusual particles helps scientists advance our knowledge of the strong force, one of the four known fundamental forces in the universe. At a CERN seminar held virtually on 11 August, LHCb announced the first signs of an entirely new kind of tetraquark with a mass of 2.9 GeV/c²: the first such particle with only one charm quark.

First predicted to exist in 1964, scientists have observed six kinds of quarks (and their antiquark counterparts) in the laboratory: up, down, charm, strange, top and bottom. Since quarks cannot exist freely, they group to form composite particles: three quarks or three antiquarks form “baryons” like the proton, while a quark and an antiquark form “mesons”.

The LHCb detector at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is devoted to the study of B mesons, which contain either a bottom or an antibottom. Shortly after being produced in proton–proton collisions at the LHC, these heavy mesons transform – or “decay” – into a variety of lighter particles, which may undergo further transformations themselves. LHCb scientists observed signs of the new tetraquark in one such decay, in which the positively charged B meson transforms into a positive D meson, a negative D meson and a positive kaon: B+→D+D−K+. In total, they studied around 1300 candidates for this particular transformation in all the data the LHCb detector has recorded so far.

One of the most consumed drugs in the US – and the most commonly taken analgesic worldwide – could be doing a lot more than simply taking the edge off your headache, recent evidence suggests.

Acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol and sold widely under the brand names Tylenol and Panadol, also increases risk-taking, according to a September 2020 study that measured changes in people’s behaviour when under the influence of the common over-the-counter medication.

“Acetaminophen seems to make people feel less negative emotion when they consider risky activities – they just don’t feel as scared,” said neuroscientist Baldwin Way from The Ohio State University in September 2020.

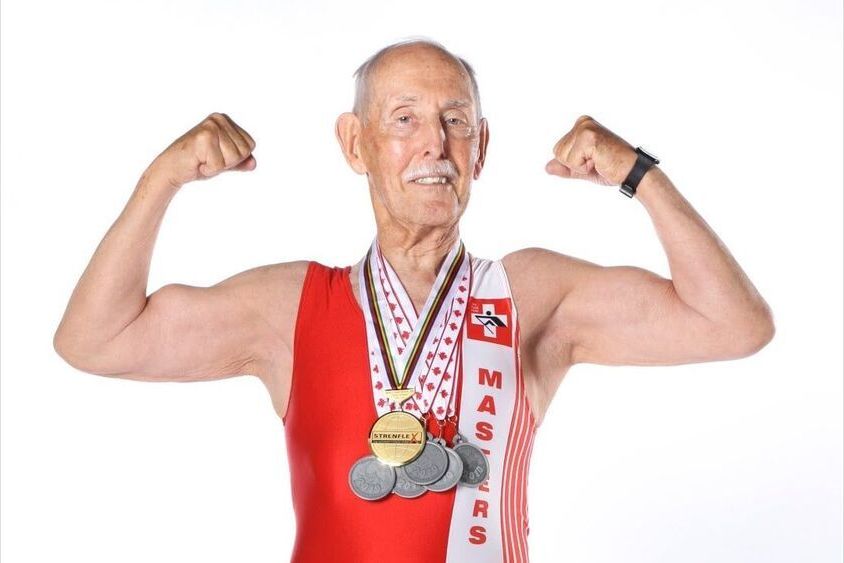

I am sure you know weak bones break more easily, and the older you get the worse any extended periods of inactivity are, on not just your present health and well being, but also your longevity.

So whether you are lifting free weights for the fun of it, using your body weight in a home scenario or engaging in daily activities you know are physically taxing, you should really be incorporating some form of strength training in your plans for longevity.

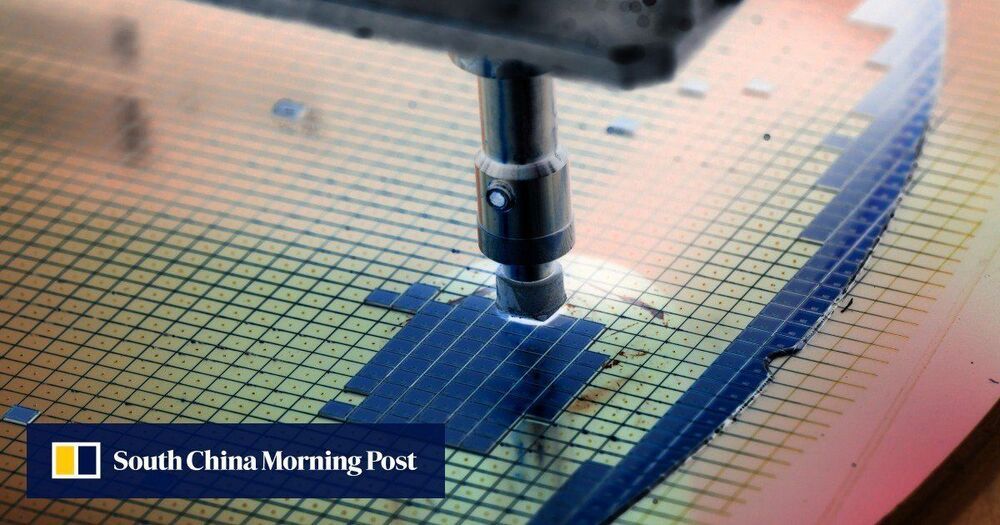

To that end, a large number of overseas trained and educated Chinese nationals have heeded the call and returned to China to establish start-ups in the semiconductor field, ranging from electronic design automation (EDA) software and IC design to silicon foundry and wafer processing equipment.

Many overseas trained and educated Chinese nationals have returned to China to establish start-ups in the semiconductor field, ranging from IC design to chipmaking tools. Here are 10 of them.