You can’t always change your feelings. But you can change how you manage those feelings.

It’s only the second time pristine astroid material has been brought back to Earth.

A Japanese space capsule carrying asteroid samples landed in a remote area of Australia as planned Saturday, Japan’s space agency, JAXA, said.

Why it matters via Axios’ Miriam Kramer: It’s only the second time pristine asteroid material has been brought back to Earth. Sample return missions like this one are incredibly valuable to scientists.

This article was published as a part of the Data Science Blogathon.

Introduction

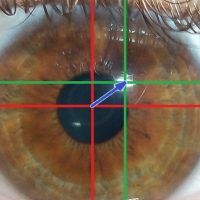

Hi, In this article, let us go over how you can create a Python program using Convolutional Neural Networks (Deep Learning) and a mouse/keyboard automation library called pyautogui to move your mouse/cursor with your head pose. We will be using pyautogui as it is the simplest available Python library to programmatically control the various components of your computer. More details on how to use this library mentioned below.

Now that EAST has switched on for what its makers say is the real deal, the project has a lot to prove. It costs a huge amount of energy input to bring a tokamak reactor’s entire assembly up to speed. If a fusion reactor can’t easily outpace that input, it will never produce power, let alone the dream of virtually limitless power that fusion proponents have sold for decades.

China has switched on its record-setting “artificial sun” tokamak, state media reported today. This begins a timeline China hopes will be similar to the one planned by the global International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project.

☢️ You love nuclear. So do we. Let’s nerd out over nuclear together.

Mexico’s Senate approved a bill to legalize marijuana nationally on Thursday.

Before it can become law it must also be passed by the other body of the country’s Congress, the Chamber of Deputies.

The legislation, which was circulated in draft form earlier this month, would establish a regulated cannabis market in Mexico, allowing adults 18 and older to purchase and possess up to 28 grams of marijuana and cultivate up to six plants for personal use.

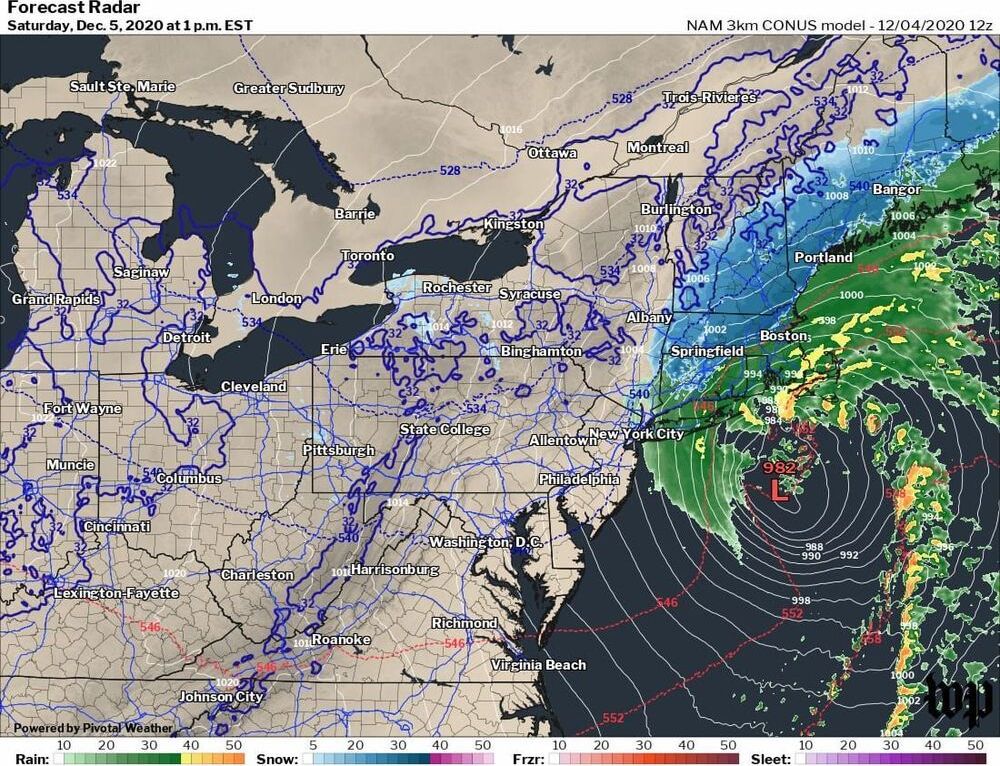

Hayabusa2’s sample return capsule has landed in Woomera, Australia, today, 5 December — or 6 December local time at Woomera. The exact landing location is now being determined, but a tweet from the mission’s official account says an estimated location of landing has been identified and teams are en route to recover it.

The craft returned not just asteroid surface material, but subsurface material (at first) as well, and will be met by Japanese scientists after completing its six-year mission to the asteroid 162173 Ryugu.

The main Hayabusa2 spacecraft meanwhile used its remaining propellant to start an extended, 11 year astronomical mission.

Just a few doses of an experimental drug can reverse age-related declines in memory and mental flexibility in mice, according to a new study by UC San Francisco scientists. The drug, called ISRIB, has already been shown in laboratory studies to restore memory function months after traumatic brain injury (TBI), reverse cognitive impairments in Down Syndrome, prevent noise-related hearing loss, fight certain types of prostate cancer, and even enhance cognition in healthy animals.

In the new study, published Dec. 1, 2020, in the open-access journal eLife, researchers showed rapid restoration of youthful cognitive abilities in aged mice, accompanied by a rejuvenation of brain and immune cells that could help explain improvements in brain function.

“ISRIB’s extremely rapid effects show for the first time that a significant component of age-related cognitive losses may be caused by a kind of reversible physiological “blockage” rather than more permanent degradation,” said Susanna Rosi, PhD, Lewis and Ruth Cozen Chair II and professor in the departments of Neurological Surgery and of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science.