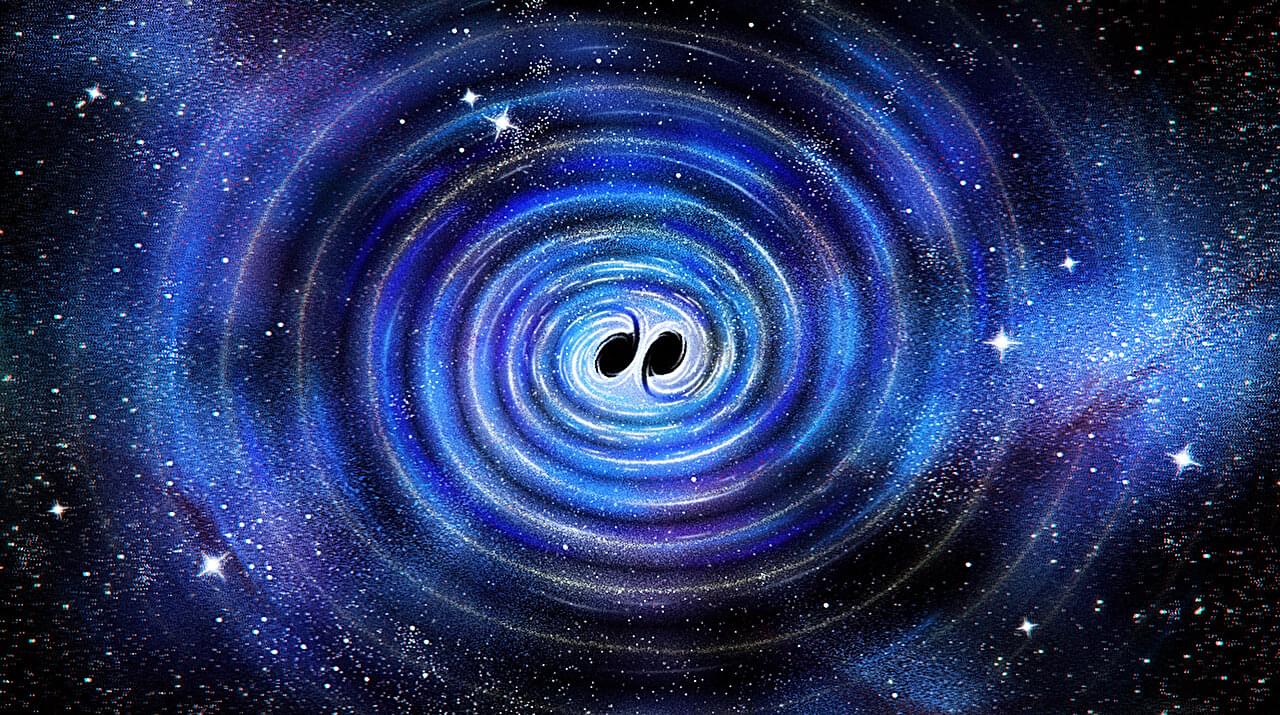

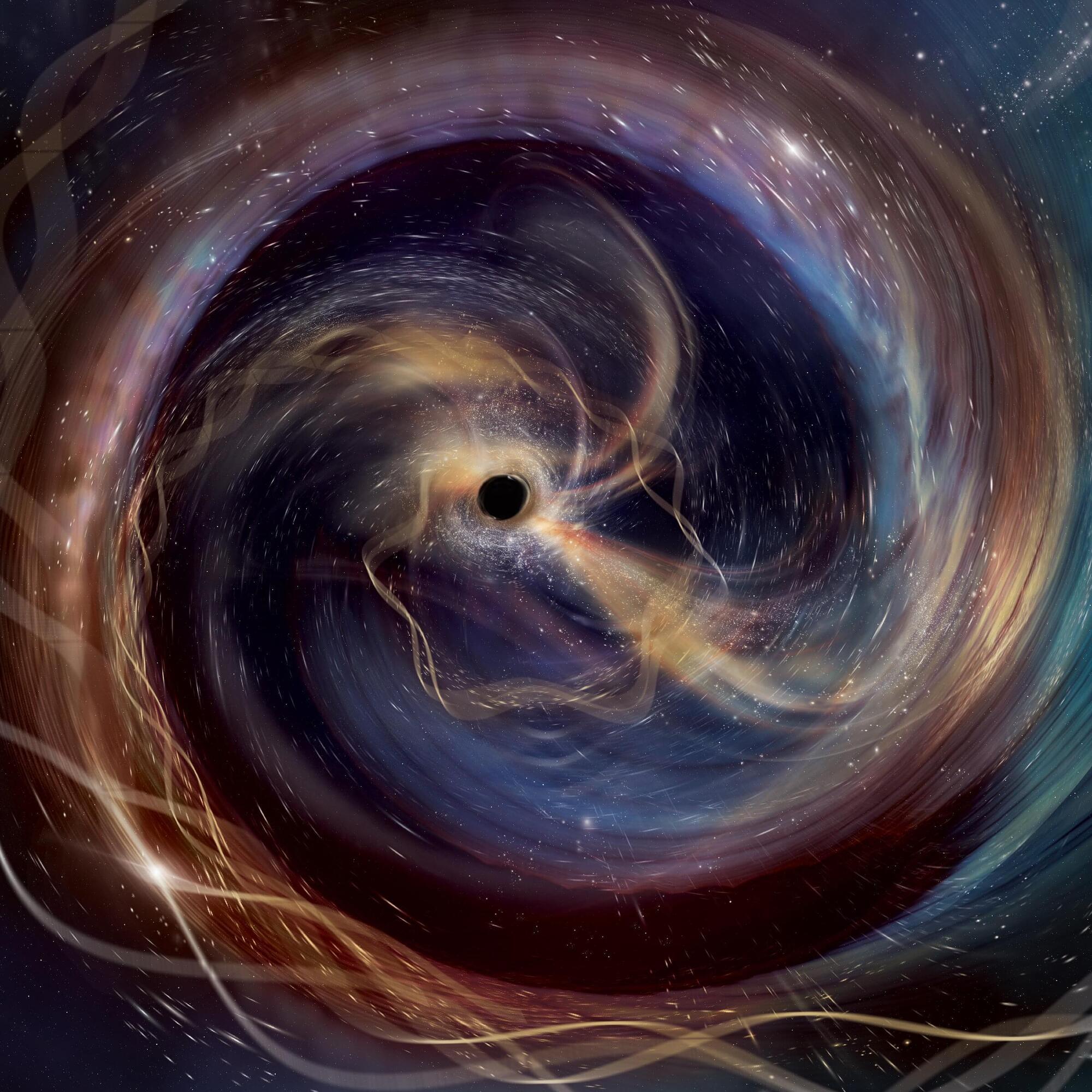

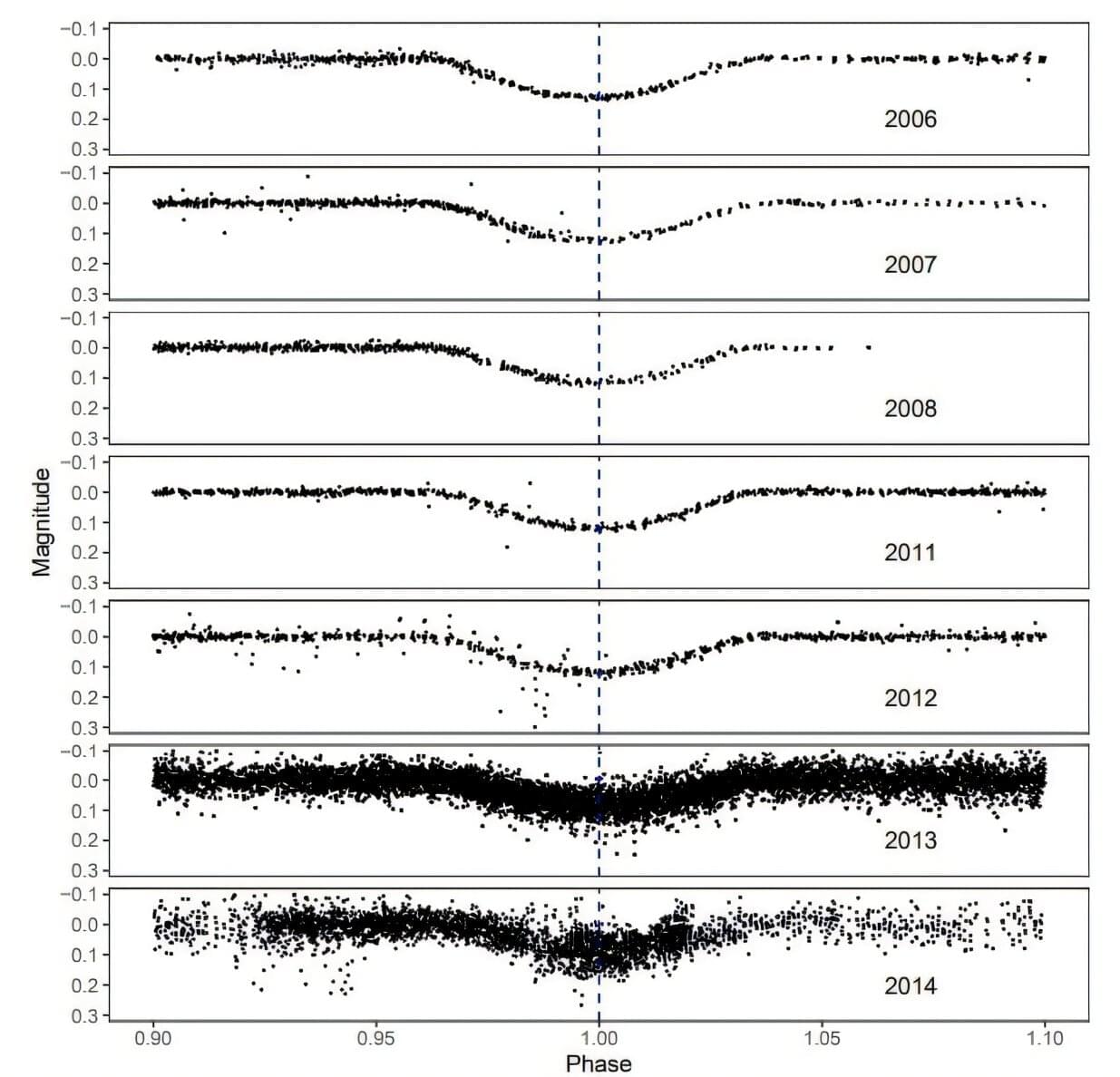

A decade ago, scientists first detected ripples in the fabric of space-time, called gravitational waves, from the collision of two black holes. Now, thanks to improved technology and a bit of luck, a newly detected black hole merger is providing the clearest evidence yet of how black holes work—and, in the process, offering long-sought confirmation of fundamental predictions by Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking.

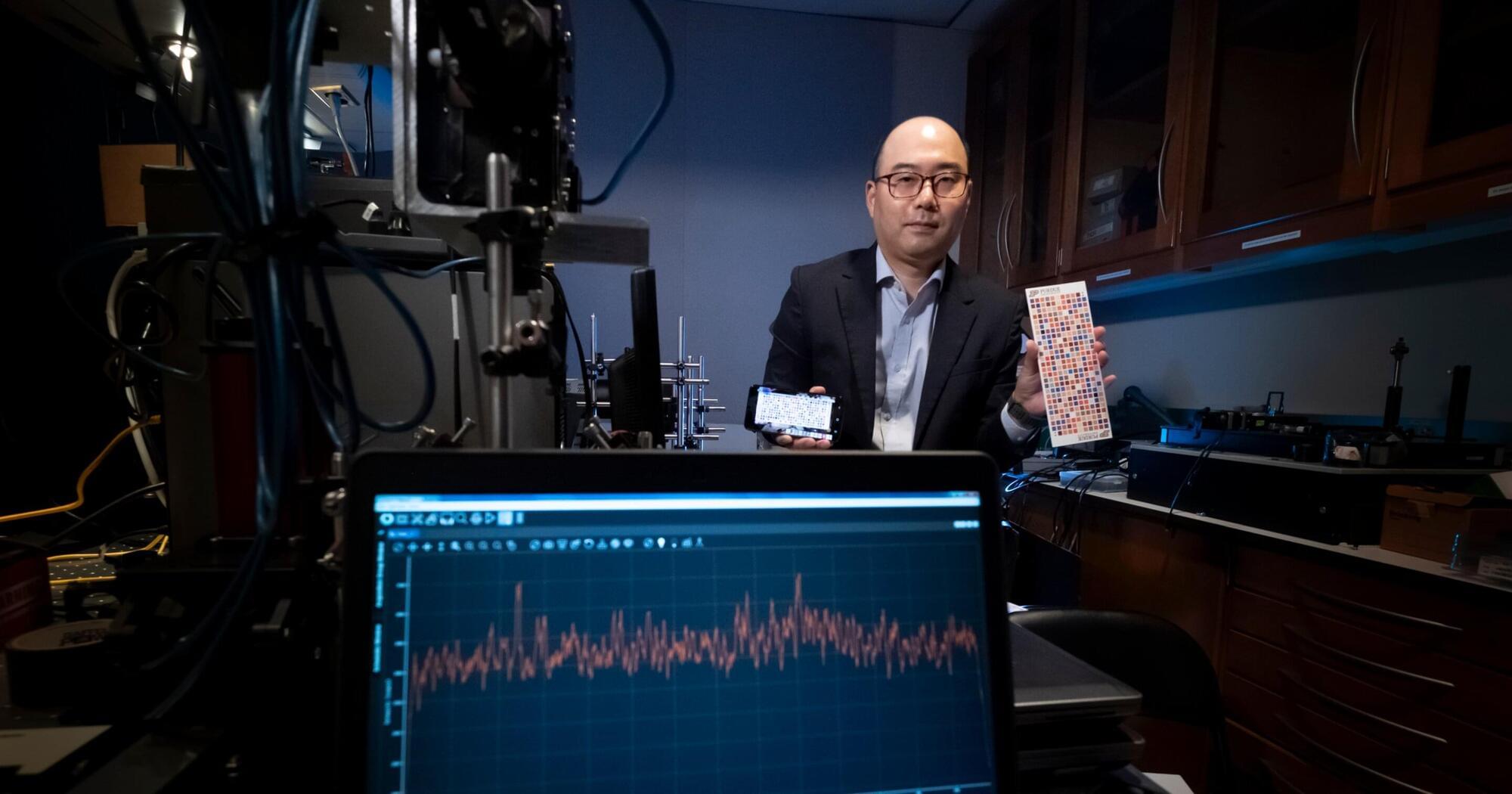

The new measurements were made by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), with analyses led by astrophysicists Maximiliano Isi and Will Farr of the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics in New York City. The results reveal insights into the properties of black holes and the fundamental nature of space-time, hinting at how quantum physics and Einstein’s general relativity fit together.

“This is the clearest view yet of the nature of black holes,” says Isi, who is also an assistant professor at Columbia University. “We’ve found some of the strongest evidence yet that astrophysical black holes are the black holes predicted from Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity.”