New research from the University of Rochester will enhance the accuracy of computer models used in simulations of laser-driven implosions. The research, published in the journal Nature Physics, addresses one of the challenges in scientists’ longstanding quest to achieve fusion.

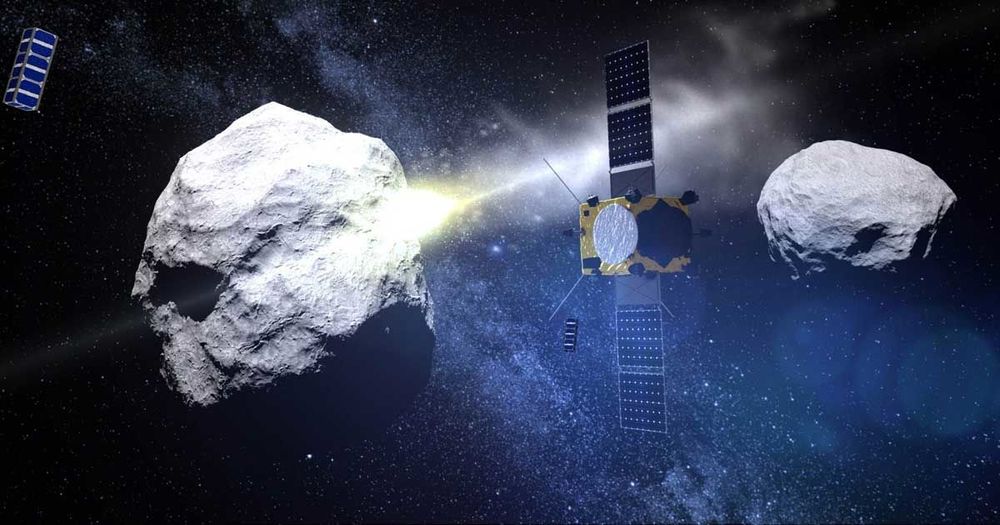

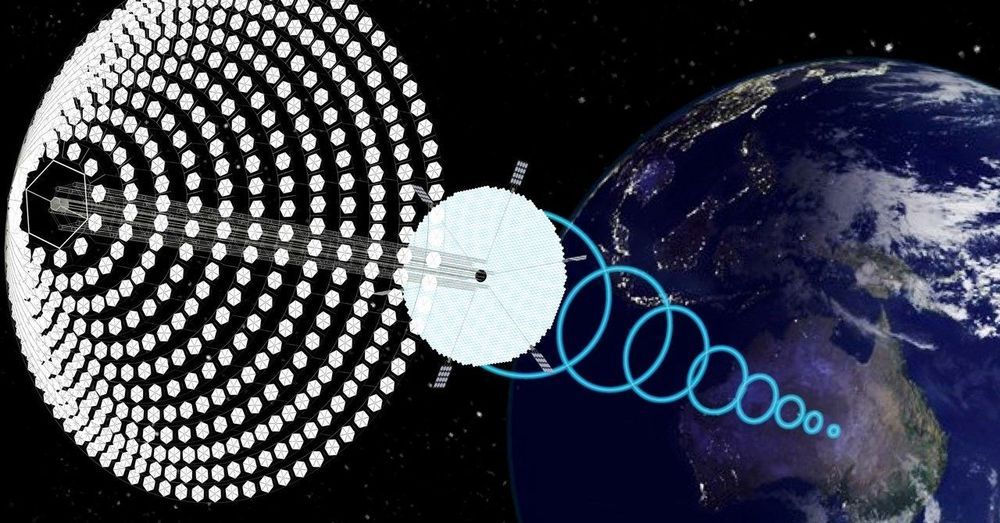

In laser-driven inertial confinement fusion (ICF) experiments, such as the experiments conducted at the University of Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics (LLE), short beams consisting of intense pulses of light—pulses lasting mere billionths of a second—deliver energy to heat and compress a target of hydrogen fuel cells. Ideally, this process would release more energy than was used to heat the system.

Laser-driven ICF experiments require that many laser beams propagate through a plasma—a hot soup of free moving electrons and ions—to deposit their radiation energy precisely at their intended target. But, as the beams do so, they interact with the plasma in ways that can complicate the intended result.