The Newtonian laws of physics explain the behavior of objects in the everyday physical world, such as an apple falling from a tree. For hundreds of years Newton provided a complete answer until the work of Einstein introduced the concept of relativity. The discovery of relativity did not suddenly prove Newton wrong, relativistic corrections are only required at speeds above about 67 million mph. Instead, improving technology allowed both more detailed observations and techniques for analysis that then required explanation. While most of the consequences of a Newtonian model are intuitive, much of relativity is not and is only approachable though complex equations, modeling, and highly simplified examples.

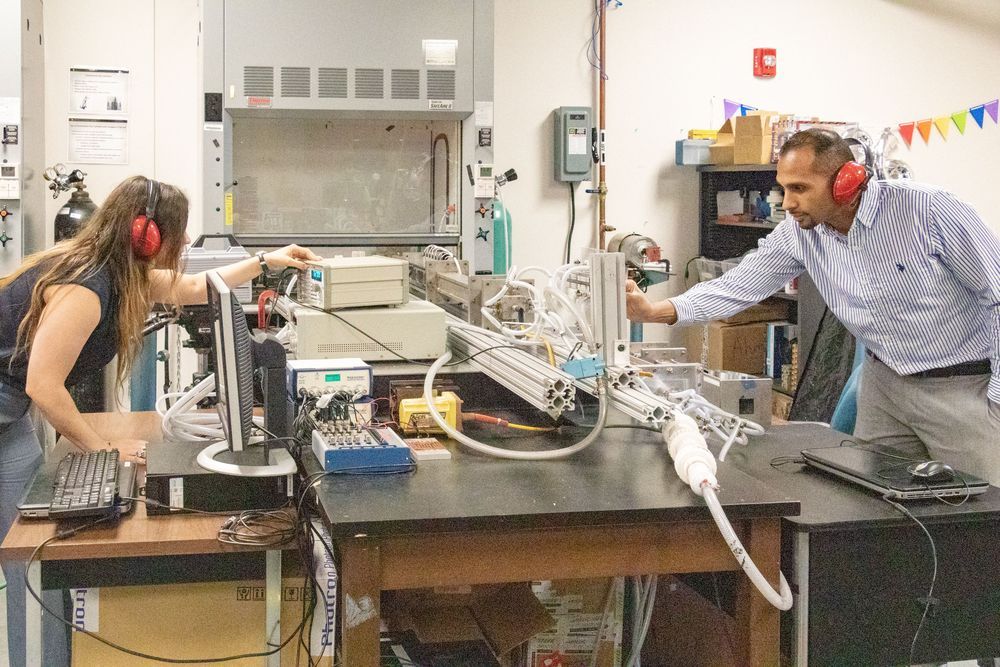

In this issue, Korman et al.1 provide data from a model of the second gas effect on arterial partial pressures of volatile anesthetic agents. Most readers might wonder what this information adds, some will struggle to remember what the second gas effect is, and others will query the value of modeling rather than “real data.” This editorial attempts to address these questions.

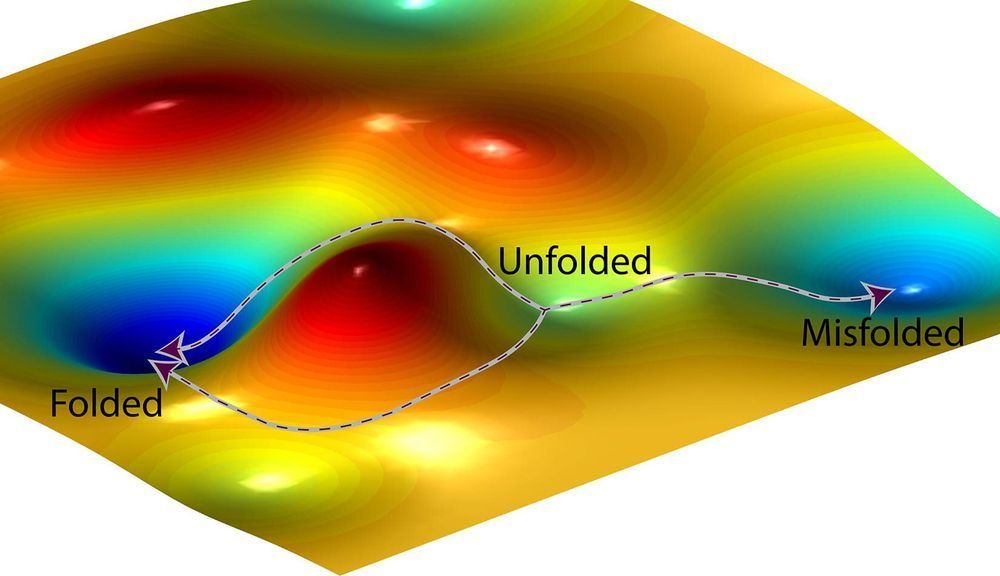

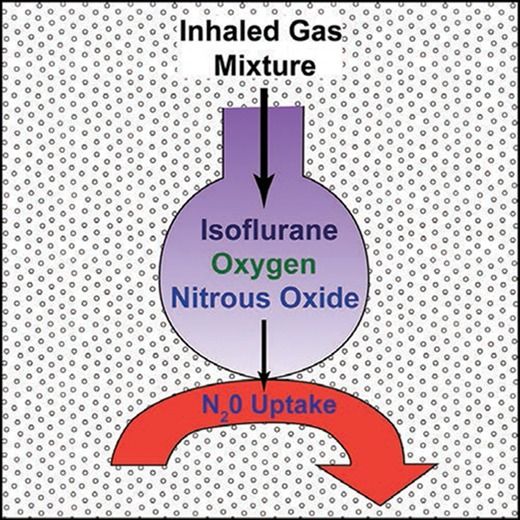

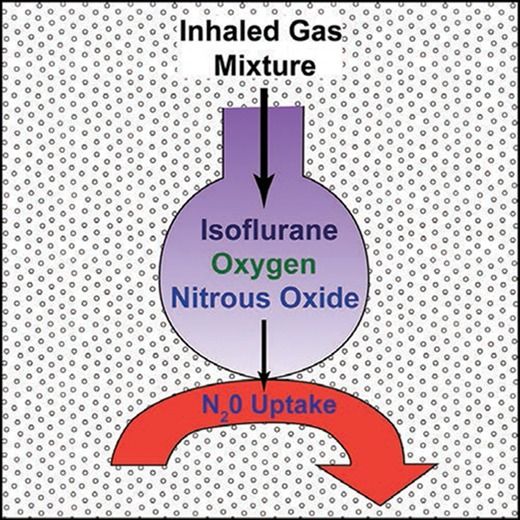

The second gas effect2 is a consequence of the concentration effect3 where a “first gas” that is soluble in plasma, such as nitrous oxide, moves rapidly from the lungs to plasma. This increases the alveolar concentration and hence rate of uptake into plasma of the “second gas.” The second gas is typically a volatile anesthetic, but oxygen also behaves as a second gas.4 Although we frequently talk of inhalational kinetics as a single process, there are multiple steps between dialing up a concentration and the consequent change in effect. The key steps are transfer from the breathing circuit to alveolar gas, from the alveoli to plasma, and then from plasma to the “effect-site.” Separating the two steps between breathing circuit and plasma helps us understand both the second gas effect and the message underlying the paper by Korman et al.1