💼

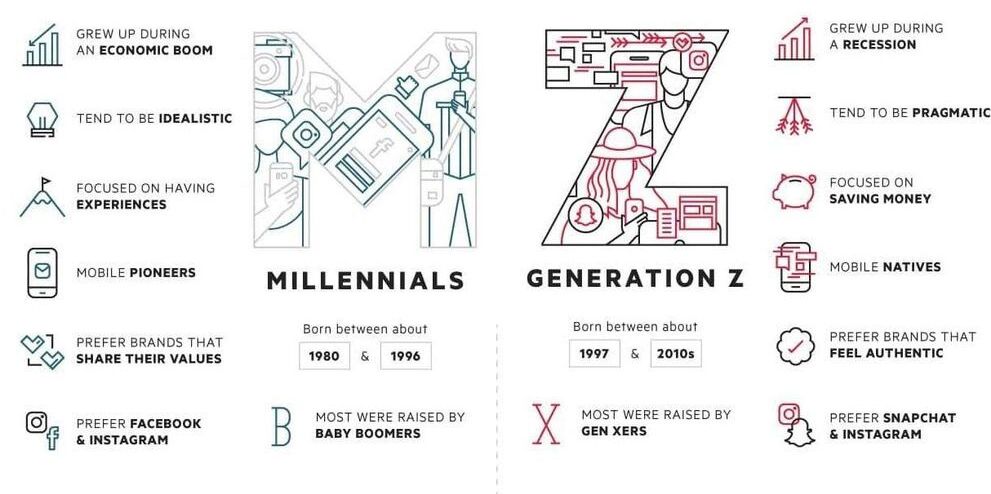

As Millennials enter their early-30s, the focus is now shifting to Generation Z — a group that is just starting to enter the workforce for the first time.

DART is a planetary defense-driven test of technologies for preventing an impact of Earth by a hazardous asteroid. DART will be the first demonstration of the kinetic impactor technique to change the motion of an asteroid in space. The DART mission is in Phase C, led by APL and managed under NASA’s Solar System Exploration Program at Marshall Space Flight Center for NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office and the Science Mission Directorate’s Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC.

NASA brings you images, videos and features from the unique perspective of America’s space agency. Get updates on missions, watch NASA TV, read blogs, view the latest discoveries, and more.

A 75-year-old man from Northern Israel died of a heart attack about two hours after being vaccinated against the novel coronavirus, the Health Ministry has confirmed. The man had pre-existing conditions and had suffered from heart attacks in the past, the ministry said. Health Ministry director-general Chezy Levy has launched an investigation into the incident. “We share in the grief of the family,” Levy said in a statement. The man was inoculated at around 8:30 a.m. at a Clalit clinic. He stayed at the facility, as is customary, for a short period of time to ensure he had no side effects. When he felt well, the clinic released him. Levy noted that the initial findings do not show a link between the man’s death and his vaccination. Recall that when Pfizer presented its safety data to the US Food and Drug Administration back in early December, it was found that two trial participants had died after receiving the vaccine.

A 75-year-old man from Beit She’an died of a heart attack about two hours after being vaccinated against the novel coronavirus on Monday morning, the Health Ministry reported. The man had preexisting conditions and had suffered from heart attacks in the past, it said. Health Ministry director-general Chezy Levy has launched an investigation into the incident. “We share in the grief of the family,” he said in a statement. The man was inoculated at around 8:30 a.m. at a Clalit Health Services clinic. He stayed at the facility, as is customary, for a short period of time to ensure he had no side effects. When he felt well, the clinic released him. The initial findings do not show a link between the man’s death and his vaccination, Levy said. When Pfizer presented its safety data to the US Food and Drug Administration in early December, it was found that two trial participants had died after receiving the vaccine. One of the deceased was immunocompromised, meaning the person’s immune defenses were low. In response to the report of those deaths, Israel’s Midaat Association said when vaccines are administered to at-risk populations, “there may be unfortunate cases. One should not infer from this about the safety of the vaccine, but welcome the transparency required from the pharma companies in the drug approval process.”

SpaceX’s fleet of reusable Falcon 9 rockets enabled it to conduct more missions in 2020 than ever before. SpaceX completed a record-breaking launch manifest this year, it conducted 26 rocket launches –the most annual launches it has performed in history. Rocket reusability has played a significant role in increasing launch cadence. Falcon 9 is capable of launching payload to orbit and returning from space to land vertically on landing pads and autonomous droneships at sea. To date, SpaceX has landed 70 orbital-class Falcon 9 boosters and reused 49. This year the company accomplished flying two particular rocket boosters 7 times. Engineers aim to reuse a first-stage booster at least 10 times to reduce the cost of spaceflight. The most reused Falcon 9 rockets that reached 7 reflights this year are two first-stage boosters identified as B1051 and B1049. SpaceX is just three flights away from achieving 10 reflights. SpaceX officials state Falcon 9 [Block 5] is designed to perform up to 100 reflights.

Stephen Marr, a spaceflight photographer who goes by the name @spacecoast_stve on Twitter, shared a photo collage of all the Falcon 9 boosters used in 2020, “SpaceX carried out a record-breaking 26 launches this year, but how many boosters did it take to get it done? The answer is 11. And here they are!” he wrote. SpaceX founder Elon Musk replied to Marr’s tweet –“Falcon was 25% of successful orbital launches in 2020, but maybe a majority of payload to orbit. Anyone done the math?” he said.

It seems even police cars are moving to Tesla. 😃

Tesla Model Y enters the world of crime-fighting, commissioned by the Hastings-on-Hudson Police Department, Westchester County, New York. This is the first Model Y that has already been purchased and equipped as a police department vehicle in the world.

On December 21, the Hastings-on-Hudson Police Department shared the great news with the community via their Facebook. The PD has acquired and has already received their first electric car—Tesla Model Y. Police Chief David Dosin said the Westchester County Department was the first in the county to receive delivery of the all-electric police car, as the department is committed to alternative fuels and clean technologies.

Hastings PD introduces the first police outfitted Tesla Model Y in the US!!

The Hastings PD took delivery of a brand new Tesla Model Y today! It will serves as the police car assigned to the Detective Division.

You want 2021 to be super. But not in a super gonorrhea type of way.

“Super gonorrhea” is trending on Twitter right now because, well, why not? It’s 2020, after all. And what better thing to have trend at the end of a year that brought us the Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic, a shortage of basically everything, constant drama in the White House, and a Presidential election that just won’t end? Consider this sexually transmitted infection to be the pie à la mode, the night cap, the final wipe of 2020.

This new anti-cancer drug will be attacking the mitochondria of cancer cells. They do this by inhibiting the enzyme mitochondrial RNA polymerase (POLRMT).

Differentiated tissues are said to be tolerant of the inhibition of this enzyme while rapidly proliferating cells are impacted more.

The compound was found to reduce tumor growth in mice.