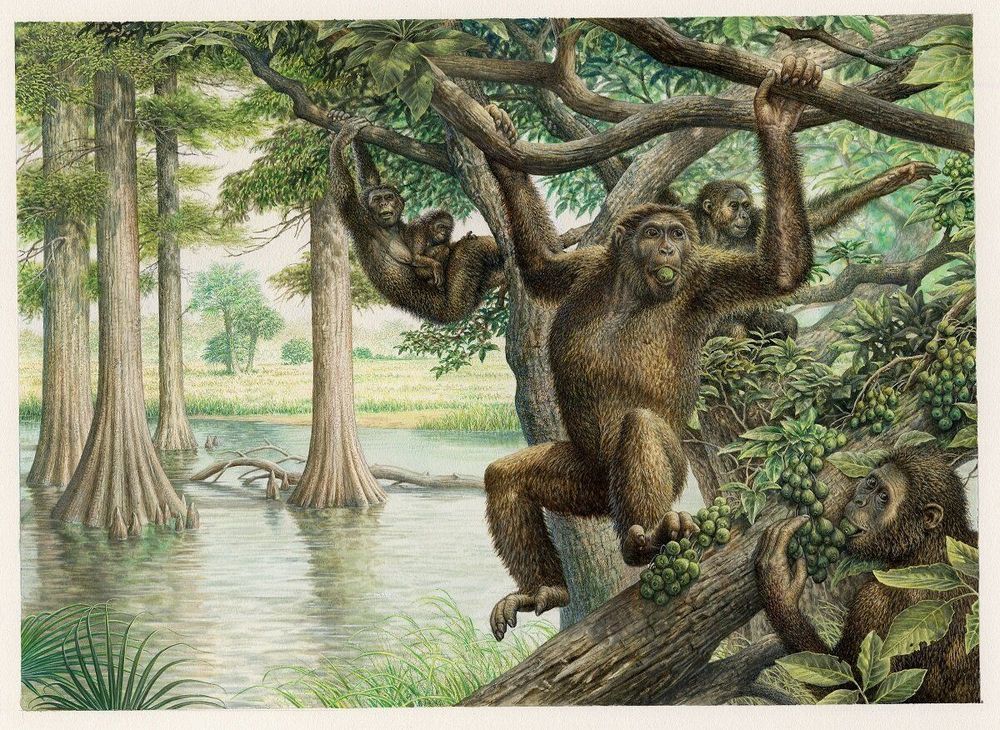

Near an old mining town in Central Europe, known for its picturesque turquoise-blue quarry water, lay Rudapithecus. For 10 million years, the fossilized ape waited in Rudabánya, Hungary, to add its story to the origins of how humans evolved.

What Rudabánya yielded was a pelvis—among the most informative bones of a skeleton, but one that is rarely preserved. An international research team led by Carol Ward at the University of Missouri analyzed this new pelvis and discovered that human bipedalism—or the ability for people to move on two legs—might possibly have deeper ancestral origins than previously thought.

The Rudapithecus pelvis was discovered by David Begun, a professor of anthropology at the University of Toronto who invited Ward to collaborate with him to study this fossil. Begun’s work on limb bones, jaws and teeth has shown that Rudapithecus was a relative of modern African apes and humans, a surprise given its location in Europe. But information on its posture and locomotion has been limited, so the discovery of a pelvis is important.