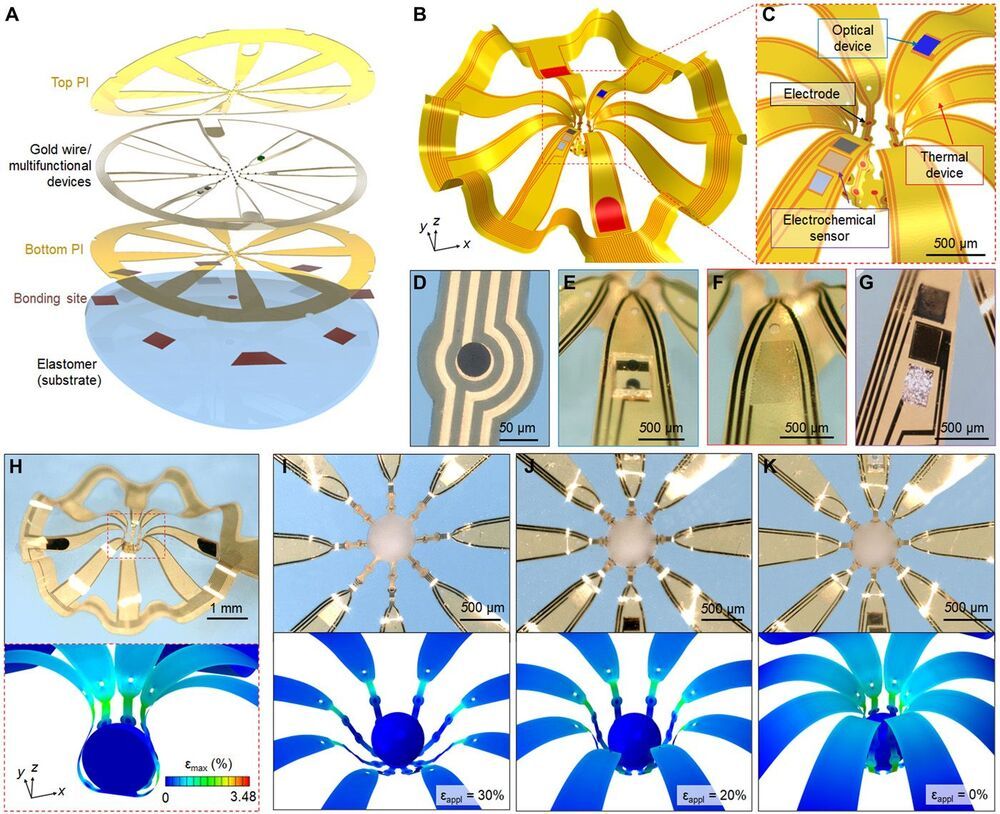

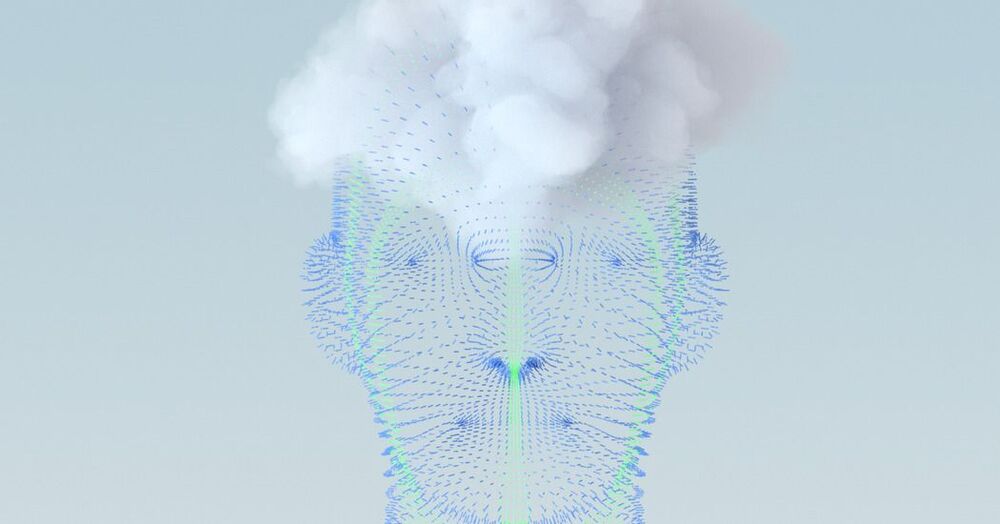

Three-dimensional (3D), submillimeter-scale constructs of neural cells, known as cortical spheroids, are of rapidly growing importance in biological research because these systems reproduce complex features of the brain in vitro. Despite their great potential for studies of neurodevelopment and neurological disease modeling, 3D living objects cannot be studied easily using conventional approaches to neuromodulation, sensing, and manipulation. Here, we introduce classes of microfabricated 3D frameworks as compliant, multifunctional neural interfaces to spheroids and to assembloids. Electrical, optical, chemical, and thermal interfaces to cortical spheroids demonstrate some of the capabilities. Complex architectures and high-resolution features highlight the design versatility. Detailed studies of the spreading of coordinated bursting events across the surface of an isolated cortical spheroid and of the cascade of processes associated with formation and regrowth of bridging tissues across a pair of such spheroids represent two of the many opportunities in basic neuroscience research enabled by these platforms.

Progress in elucidating the development of the human brain increasingly relies on the use of biosystems produced by three-dimensional (3D) neural cultures, in the form of cortical spheroids, organoids, and assembloids (1–3). Precisely monitoring the physiological properties of these and other types of 3D biosystems, especially their electrophysiological behaviors, promises to enhance our understanding of the interactions associated with development of the nervous system, as well as the evolution and origins of aberrant behaviors and disease states (4–8). Conventional multielectrode array (MEA) technologies exist only in rigid, planar, and 2D formats, thereby limiting their functional interfaces to small areas of 3D cultures, typically confined to regions near the bottom contacting surfaces.