In nuclear physics, like much of science, detailed theories alone aren’t always enough to unlock solid predictions. There are often too many pieces, interacting in complex ways, for researchers to follow the logic of a theory through to its end. It’s one reason there are still so many mysteries in nature, including how the universe’s basic building blocks coalesce and form stars and galaxies. The same is true in high-energy experiments, in which particles like protons smash together at incredible speeds to create extreme conditions similar to those just after the Big Bang.

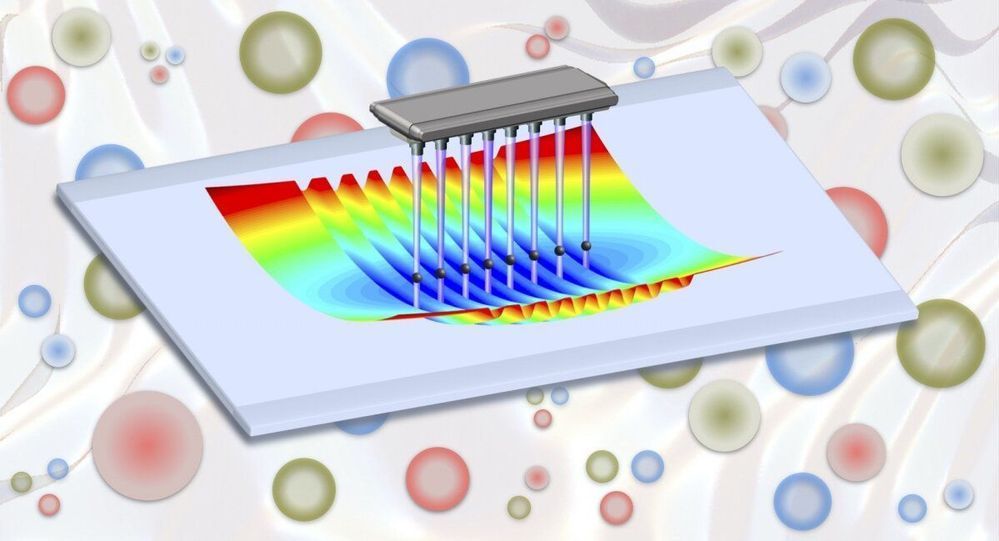

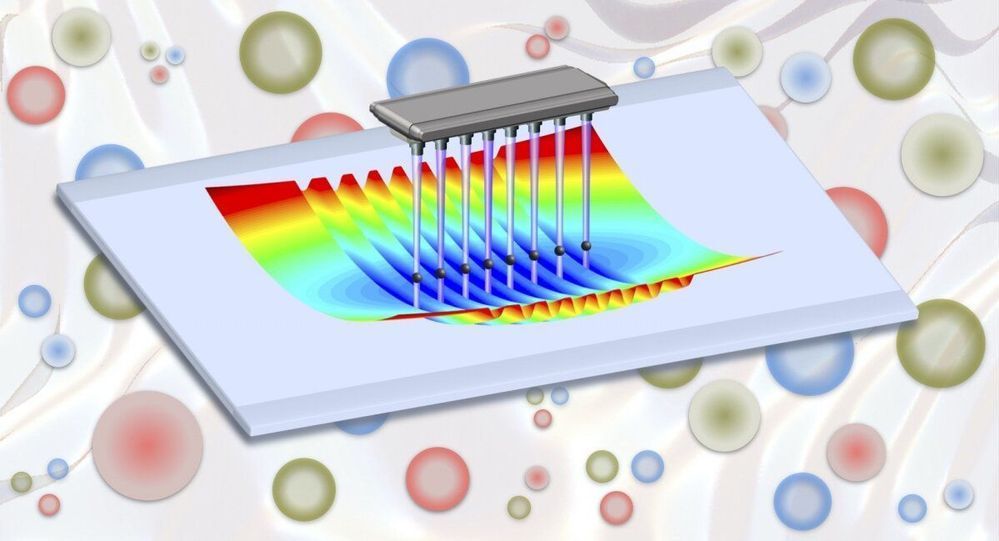

Fortunately, scientists can often wield simulations to cut through the intricacies. A simulation represents the important aspects of one system—such as a plane, a town’s traffic flow or an atom—as part of another, more accessible system (like a computer program or a scale model). Researchers have used their creativity to make simulations cheaper, quicker or easier to work with than the formidable subjects they investigate—like proton collisions or black holes.

Simulations go beyond a matter of convenience; they are essential for tackling cases that are both too difficult to directly observe in experiments and too complex for scientists to tease out every logical conclusion from basic principles. Diverse research breakthroughs—from modeling the complex interactions of the molecules behind life to predicting the experimental signatures that ultimately allowed the identification of the Higgs boson—have resulted from the ingenious use of simulations.