Researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Brazil have identified a robust set of genetic markers associated with meat quality in the Nelore cattle breed (Bos taurus indicus) genome. The results pave the way for substantial progress in the genetic enhancement of the Zebu breed, which accounts for about 80% of the Brazilian beef herd.

The research has direct implications for the productivity and quality of Brazilian beef, reinforcing the country’s standing as a major beef exporter. The results are published in the journal Scientific Reports.

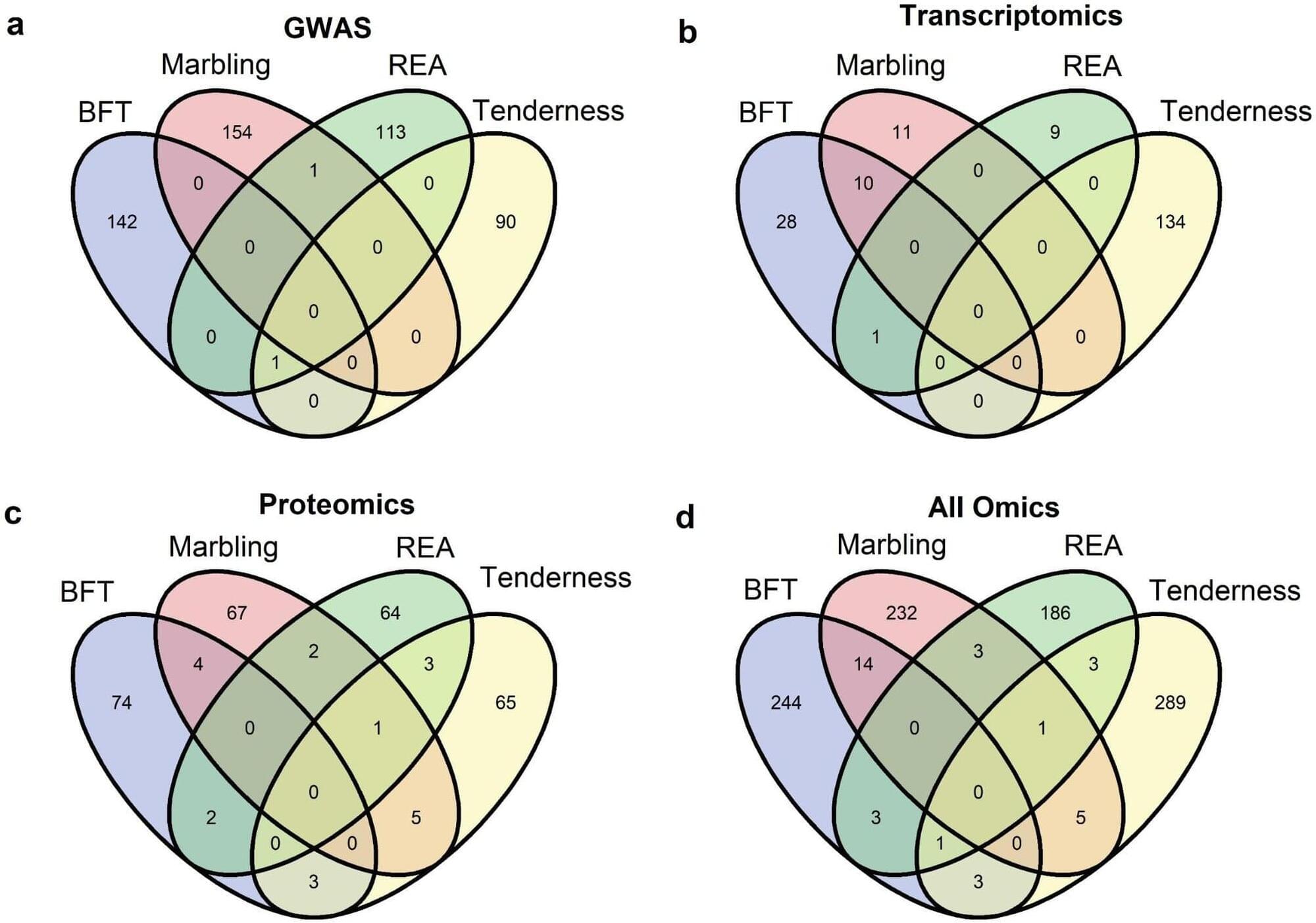

In previous studies, the group had identified genes and proteins by studying meat and carcass characteristics separately using different techniques. For the current study, however, the researchers integrated these techniques and examined multiple characteristics using data from 6,910 young Nelore bulls from four commercial genetic improvement programs.