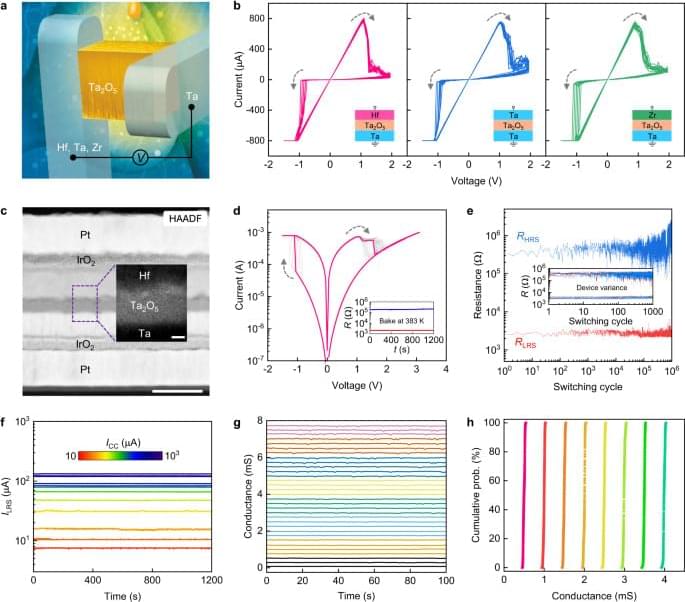

Chen et al. present a filament conductivity change mechanism in memristive devices with all ohmic electrodes, allowing for advanced functionalities and more effective emulation of the metaplasticity concept in neuroscience.

Ich arbeite zur Zeit eifrig an der 9. Episode meiner Video-Reihe über Isaac Asimov und sein Trantor/Foundation-Universum. In dem Roman \.

Innana.

All audio from King of Digital iOS app.

Half a million people in the UK with dangerously high blood pressure – a “silent killer” that causes tens of thousands of deaths a year – could be cured by a new treatment.

Doctors have developed a technique to burn away nodules that lead to a large amount of salt building up in the body, which increases the risk of a stroke or heart attack.

The breakthrough could mean people with primary aldosteronism – which causes one in 20 cases of high blood pressure – no longer have to have surgery or spend their lives taking the drug spironolactone to lower their risk of a stroke or heart attack.

Boquila trifoliolata plants were purchased from a local store placed in Port Townsend Washington and arrived in 15.24 cm pots. Shortly after arrival plants were reported in 25.4 cm pots filled with high nutrient potting soil with a pH of 6.3, 0.30% nitrogen, 0.45% phosphate, 0.05% potassium, and 1.00% calcium. The plants were watered with distilled water (approximately 236 ml) until they reached field capacity every other day to keep the soil moist. A stone humidifier was placed near the plants to maintain a higher humidity. The experiment was conducted in Magna, Ut, USA (40°42ʹN, 112°06ʹW) during the period from September 2019 to October 2020. The plants were placed in front of a large west facing window. The first leaves sample for analysis was collected in December 2020 and the second sample was collected in June 2021.

Each plant was assigned a number and placed on a growing rack. Two artificial vines were placed above the plants on a wooden trellis. During the winter, the plants grew quickly through the leaves showed poor mimicry of the artificial plants leaves. The original plant that we had did not show good evidence of mimicry until the spring and summer. We decided to continue the experiment and see if there were better results in the warmer months.

When I’m birdwatching, I have a particular experience all too frequently. Fellow birders will point to the tree canopy and ask if I can see a bird hidden among the leaves. I scan the treetops with binoculars but, to everyone’s annoyance, I see only the absence of a bird.

Our mental worlds are lively with such experiences of absence, yet it’s a mystery how the mind performs the trick of seeing nothing. How can the brain perceive something when there is no something to perceive?

For a neuroscientist interested in consciousness, this is an alluring question. Studying the neural basis of ‘nothing’ does, however, pose obvious challenges. Fortunately, there are other – more tangible – kinds of absences that help us get a handle on the hazy issue of nothingness in the brain. That’s why I spent much of my PhD studying how we perceive the number zero.

Researchers from Würzburg have experimentally demonstrated a quantum tornado for the first time by refining an established method. In the quantum semimetal tantalum arsenide (TaAs), electrons in momentum space behave like a swirling vortex. This quantum phenomenon was first predicted eight years ago by a Dresden-based founding member of the Cluster of Excellence ct.qmat.

The discovery, a collaborative effort between ct.qmat, the research network of the Universities of Würzburg and Dresden, and international partners, has now been published in Physical Review X.

Scientists have long known that electrons can form vortices in quantum materials. What’s new is the proof that these tiny particles create tornado-like structures in momentum space—a finding that has now been confirmed experimentally. This achievement was led by Dr. Maximilian Ünzelmann, a group leader at ct.qmat—Complexity and Topology in Quantum Matter—at the Universities of Würzburg and Dresden.

Engineers examined communications, navigation, and landing gear operations, even testing compatibility with an F-15D. This milestone clears the way for more rigorous ground trials before the aircraft’s first flight.

X-59’s Electromagnetic Testing Success

NASA’s X-59, a quiet supersonic research aircraft, has successfully passed electromagnetic testing, ensuring that its systems can function safely without interference in various conditions.

The world’s demand for alternative fuels and sustainable chemical products has prompted many scientists to look in the same direction for answers: converting carbon dioxide (CO2) into carbon monoxide (CO).

But the labs of Yale chemists Nilay Hazari and James Mayer have a different chemical destination in mind. In a new study, Hazari, Mayer, and their collaborators present a new method for transforming CO2 into a chemical compound known as formate — which is used primarily in preservatives and pesticides, and which may be a potential source of more complex materials.