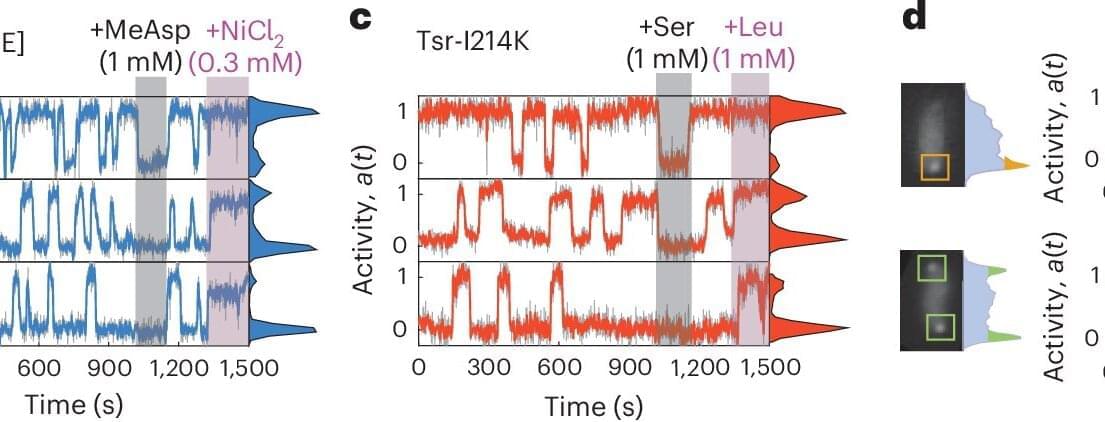

The sensory proteins that control the motion of bacteria constantly fluctuate. AMOLF researchers, together with international collaborators from ETH Zurich and University of Utah, found out that these proteins can jointly switch on and off at the same time. The researchers discovered that this protein network operates at the boundary between order and disorder. The findings are published in Nature Physics on January 29.

Bacteria may be simple, single-celled organisms, but they still have a surprisingly sophisticated way of sensing and responding to their environment. Tom Shimizu, group leader at AMOLF and senior author of the study, explains that bacteria use networks of thousands of proteins to judge whether conditions are improving or worsening.