A team of researchers from the University of Surrey’s Advanced Technology Institute (ATI) and the Federal University of Pelotas (UFPel), Brazil, has developed a new type of supercapacitor that can be integrated into footwear or clothing, an advance with applications in wearables and IoT (Internet of Things) devices.

A supercapacitor is an electricity storage device, similar to a battery, but it stores and releases electricity much faster.

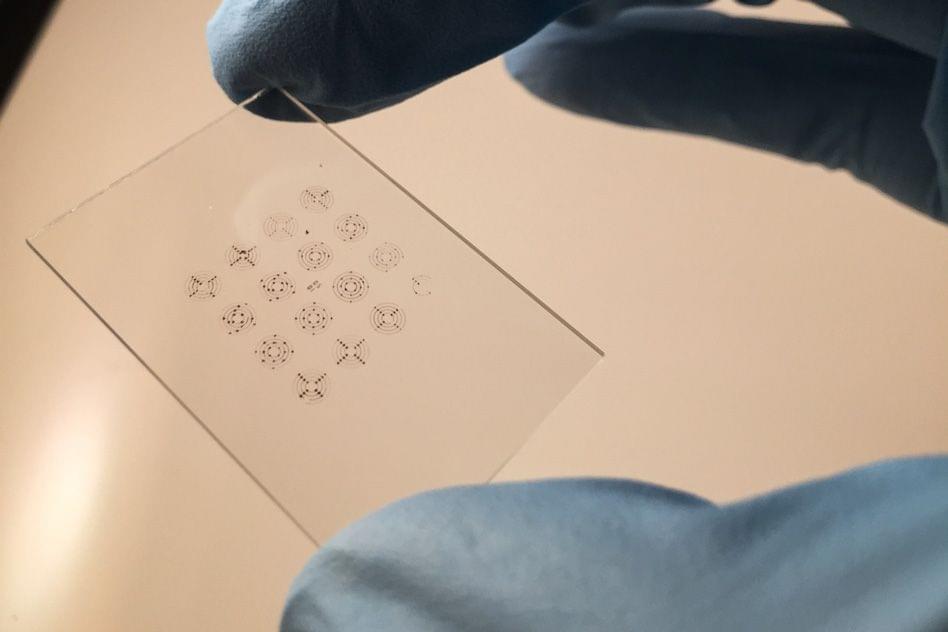

The researchers have devised a novel method for the development of flexible supercapacitors based on carbon nanomaterials. The new method, which is cheaper and less time-consuming to fabricate, involves transferring aligned carbon nanotube (CNT) arrays from a silicon wafer to a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) matrix. This is then coated in a material called polyaniline (PANI), which stores energy through a mechanism known as pseudocapacitance, offering outstanding energy storage properties with exceptional mechanical integrity.