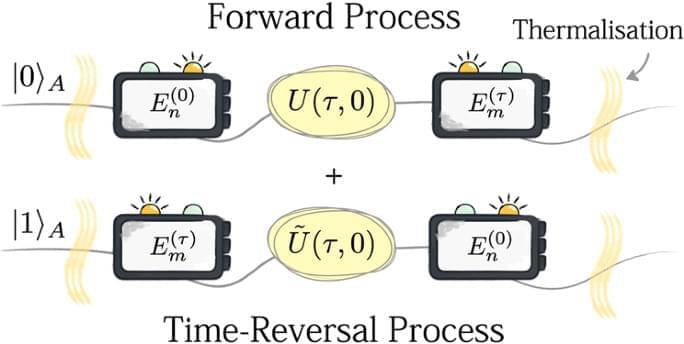

Taking a gas enclosed in a vessel as a pictorial example, the aforementioned state can be constructed by entangling the position of the piston with a further auxiliary quantum system, thereby establishing a quantum superposition of the following two processes: (i) a process wherein the gas particles are initially in thermal equilibrium confined in one half of the vessel by a piston, and the piston is pulled outwards, and (ii) the reverse process, in which the piston is pushed towards the gas, starting from an initial state where the gas occupies the entire vessel in thermal equilibrium.

We will now measure the work of the system undergoing the above-mentioned superposition of forward and time-reversal dynamics. In order to implement such a measurement, we formally construct a procedure described by a set of measurement operators forming a completely positive and trace-preserving (CPTP) map. In this regard, we will refer to a standard TPM procedure to measure work in quantum thermodynamic processes13. Implementations of the TPM in quantum setups25,26,27,28,29, as well as suitable extensions30,31,32,33, have recently received increasing attention. Our procedure can be seen as a generalisation of the TPM scheme to situations where different thermodynamic processes are allowed to be superposed, and can consequently interfere.

In the TPM scheme, work is defined as the energy difference between the initial and final states of the system, which are measured through ideal projective measurements of the system Hamiltonian implemented before and after the thermodynamic process associated with the protocol Λ34,35. This measurement scheme can be performed, individually, both for the forward and the time-reversal processes, enabling the construction of the work probability distributions P (W) and \(\tilde{P}(W)\) 0, respectively.