Cybernetics can be defined as a multidisciplinary approach to study feedback-driven systems of control between animal and machine.

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

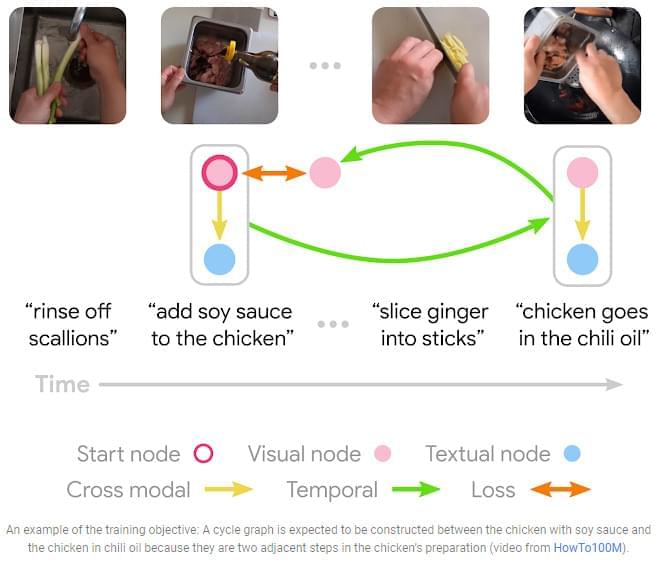

Google AI Proposes Multi-Modal Cycle Consistency (MMCC) Method Making Better Future Predictions

By Watching Unlabeled Videos.

Recent advances in machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are increasingly being adopted by people worldwide to make decisions in their daily lives. Many studies are now focusing on developing ML agents that can make acceptable predictions about the future over various timescales. This would help them anticipate changes in the world around them, including the actions of other agents, and plan their next steps. Making judgments require accurate future prediction necessitates both collecting important environmental transitions and responding to how changes develop over time.

Previous work in visual observation-based future prediction has been limited by the output format or a manually defined set of human activities. These are either overly detailed and difficult to forecast, or they are missing crucial information about the richness of the real world. Predicting “someone jumping” does not account for why they are jumping, what they are jumping onto, and so on. Previous models were also meant to make predictions at a fixed offset into the future, which is a limiting assumption because we rarely know when relevant future states would occur.

A new Google study introduces a Multi-Modal Cycle Consistency (MMCC) method, which uses narrated instructional video to train a strong future prediction model. It is a self-supervised technique that was developed utilizing a huge unlabeled dataset of various human actions. The resulting model operates at a high degree of abstraction, can anticipate arbitrarily far into the future, and decides how far to predict based on context.

Google launches Bot-in-a-Box to nudge along conversational AI

The new feature is part of Google’s Business Messages, a conversational messaging service that allows organizations to connect with people via Google Search, Google Maps, or their own business channels. For instance, Albertsons used Business Messages to share information with customers about vaccine administration. Suppose someone searched on Google for Safeway (an Albertson’s company). In that case, they could use the “message” button on Google Search to receive information like vaccine availability and how to book an appointment.

The new Bot-in-a-Box feature lets businesses launch a chatbot with an existing customer FAQ document, whether it’s from a web page or an internal document, to keep the service simple. The feature uses Google’s Dialogflow technology to create chatbots that can automatically understand and respond to customer questions without writing any code.

What Apple’s New Repair Program Means for You (and Your iPhone)

Apple delivered an early holiday gift to the eco-conscious and the do-it-yourselfers: It said it would soon begin selling the parts, tools and instructions for people to do their own iPhone repairs. It was a major victory for the “right to repair” movement.

Apple said it would soon provide parts, tools and manuals to those who wanted to fix their own iPhones and Mac computers.

Russia’s missile test could have easily obliterated the International Space Station

In the wee morning hours of Tuesday (Nov. 16), the seven-person crew of the International Space Station (ISS) awoke in alarm. A Russian missile test had just blasted a decommissioned Kosmos spy satellite into more than 1,500 pieces of space debris — some of which were close enough to the ISS to warrant emergency collision preparations.

The four Americans, one German and two Russian cosmonauts aboard the station were told to shelter in the transport capsules that brought them to the ISS, while the station passed by the debris cloud several times over the following hours, according to NASA.

Ultimately, Tuesday ended without any reported damage or injury aboard the ISS, but the crew’s precautions — and the NASA administrator’s stern response to Russia — were far from an overreaction. Space debris like the kind created in the Kosmos break-up can travel at more than 17,500 mph (28,000 km/h), NASA says — and even a scrap of metal the size of a pea can become a potentially deadly missile in low-Earth orbit. (For comparison, a typical bullet discharged from an AR-15 rifle travels at just over 2,200 mph, or 3,500 km/h).

A Russian missile test blasted a Kosmos spy satellite into more than 1,500 pieces of space debris.

Scientists Warn of “Alien” Invasions and the Need for Planetary Biosecurity

The era of space exploration brings with it a new risk: invasion. The peril comes not from little green men arriving on flying saucers but, rather, from microbiological contamination of Earth from extraterrestrial environments and vice versa. Writing in BioScience, Anthony Ricciardi, of McGill University, and colleagues describe the dangers posed by such organisms and outline an approach to address the threat.

The authors caution that biological contamination endangers both ecosystems and human well-being. “Owing to their massive costs to resource sectors and human health, biological invasions are a global biosecurity issue requiring rigorous transboundary solutions,” say Ricciardi and colleagues. And that threat may be more immediate than previously anticipated. Despite considerable microbial caution among space agencies, say the authors, “bacterial strains exhibiting extreme resistance to ionizing radiation, desiccation, and disinfectants have been isolated in NASA

Established in 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is an independent agency of the United States Federal Government that succeeded the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). It is responsible for the civilian space program, as well as aeronautics and aerospace research. It’s vision is To discover and expand knowledge for the benefit of humanity.

Orion spacecraft production continues for Artemis 2 and 3

The arrival of the second Orion European Service Module (ESM) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in October signified the beginning of months of final assembly of the first crewed Orion spacecraft that will fly four people on the Artemis 2 mission. Following the delivery of the ESM from prime contractor Airbus Defence and Space to Orion prime contractor Lockheed Martin, the two primary elements of the Artemis 2 Orion Service Module are now being bolted together.

Lockheed Martin is processing Orion flight hardware for Artemis 2 and Artemis 3 as a part of their Assembly, Test, and Launch Operations (ATLO) in the Armstrong Operations and Checkout (O&C) Building at KSC. As they process the Artemis 2 Orion Crew and Service Modules to be mated next year, the ATLO team also received the next Crew Module (CM) pressure vessel and is also simultaneously beginning build-up of the Crew Module and Crew Module Adapter (CMA) structures for Artemis 3.

Inside the Pentagon’s $82 million Super Bowl of robots

Showdown in a Kentucky Cavern: @WashingtonPost highlights DARPA’s latest Grand Challenge — #SubTChallenge — in Sunday (11÷14) magazine story Super Bowl of R… See more.

This three-year competition raises the question: How long until humans are obsolete?

‘New world order’: Asia’s virtual influencers offer metaverse glimpse

Sporting neon hair and flawless skin, Bangkok Naughty Boo is one of a new generation of influencers in Asia promising to stay forever young, on-trend, and scandal-free — because they are computer generated.

Blurring the lines between fantasy and reality, these stars are hugely popular with teenagers in the region and will yield increasing power as interest grows in the “metaverse”, industry experts say.

“I’m 17 forever, non-binary, with a dream of becoming a pop star,” Bangkok Naughty Boo — who uses they/them pronouns — said in an introductory video sent to AFP.