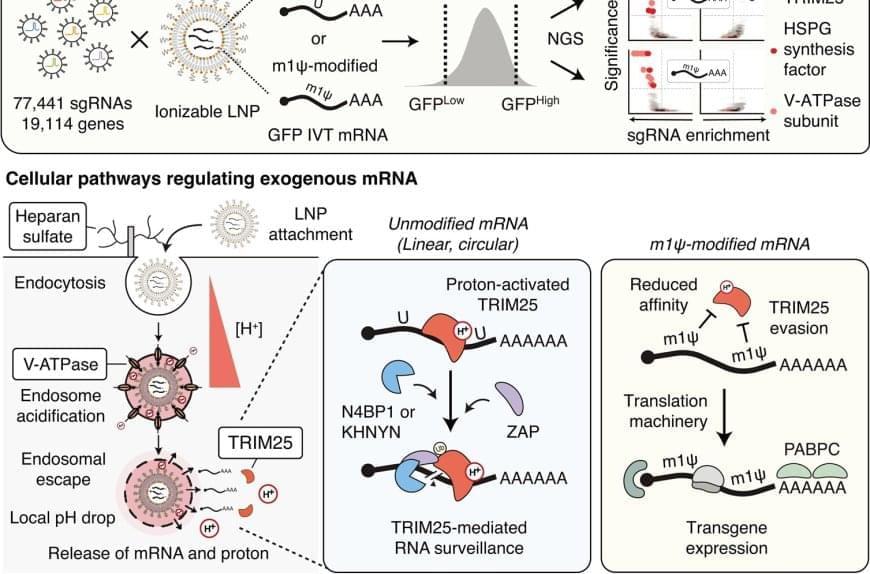

First, the team discovered that heparan sulfate (HSPG), a sulfated glycoprotein on the cell surface, plays a crucial role in attracting LNPs and facilitating mRNA entry into the cell.

- Second, they identified V-ATPase, a proton pump at the endosome, which acidifies the vesicle and causes LNPs to become positively charged, enabling them to temporarily disrupt the endosomal membrane and release the mRNA into the cytoplasm to be expressed.

- Lastly, the study uncovered the role of TRIM25, a protein involved in the cellular defense mechanism. TRIM25 binds to and induces the rapid degradation of exogenous mRNAs, preventing their function.

So how do the mRNA vaccines evade this cellular defense? A key finding of the study was that mRNA molecules containing a special modification called N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ)—which was awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine—can evade TRIM25 detection. This modification prevents TRIM25 from binding to mRNA, enhancing the stability and effectiveness of mRNA vaccines. This discovery not only explains how mRNA vaccines evade cellular surveillance mechanisms but also emphasizes the importance of this modification in enhancing the therapeutic potential of mRNA-based treatments.

Additionally, the research highlighted the critical role of proton ions in this process. When the LNPs rupture the endosomal membrane, proton ions are released into the cytoplasm, which activates TRIM25. These proton ions act as a signal that alerts the cell to the invading foreign RNA, which in turn triggers a defense response. This is the first study to demonstrate that proton ions serve as immune signaling molecules, providing new insights into how cells protect themselves from foreign RNA.

A team of researchers has uncovered a key cellular mechanism that affects the function of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. Their study, recently published in Science, provides the first comprehensive understanding of how mRNA vaccines are delivered, processed, and degraded within cells—a breakthrough that could pave the way for more effective vaccines and RNA-based treatments.