Small businesses, we want to help you navigate the federal contracting process.

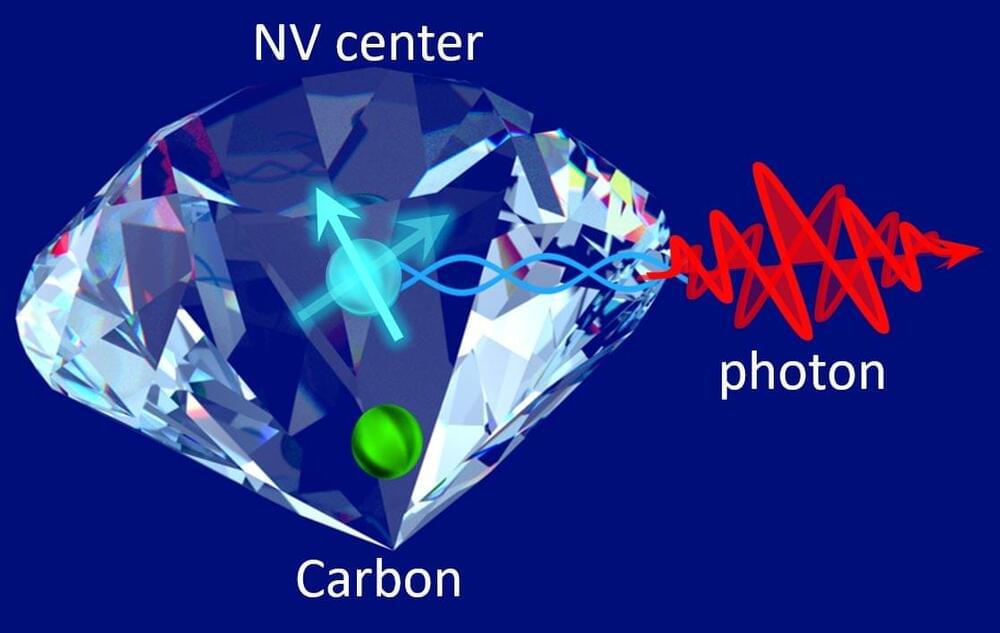

Flaws in diamonds — atomic defects where carbon is replaced by nitrogen or another element — may offer a close-to-perfect interface for quantum computing 0, a proposed communications exchange that promises to be faster and more secure than current methods. There’s one major problem, though: these flaws, known as diamond nitrogen-vacancy centers, are controlled via magnetic field, which is incompatible with existing quantum devices. Imagine trying to connect an Altair, an early personal computer developed in 1974, to the internet via WiFi. It’s a difficult, but not impossible task. The two technologies speak different languages, so the first step is to help translate.

Researchers at Yokohama National University have developed an interface approach to control the diamond nitrogen-vacancy centers in a way that allows direct translation to quantum devices. They published their method today (December 15, 2021) in Communications Physics.

“To realize the quantum internet, a quantum interface is required to generate remote quantum entanglement by photons, which are a quantum communication medium,” said corresponding author Hideo Kosaka, professor in the Quantum Information Research Center, Institute of Advanced Sciences and in the Department of Physics, Graduate School of Engineering, both at Yokohama National University. “.

Blocking matrix metalloproteinases MMP2 and MMP9 can have the opposite effect on neuroplasticity depending on whether the brain is healthy or injured.

Summary: Blocking the matrix metalloproteinases MMP2 and MMP9 can have the opposite effect on neuroplasticity depending on whether the brain is healthy or injured.

Source: University of Gottingen

The brain is a remarkably complex and adaptable organ. However, adaptability decreases with age. As new connections between nerve cells in the brain form less easily, the brain’s plasticity decreases.

If there is an injury to the central nervous system, such as after a stroke, the brain needs to compensate by reorganizing itself. To do this, a dense network of molecules between the nerve cells—known as the extracellular matrix—must loosen.

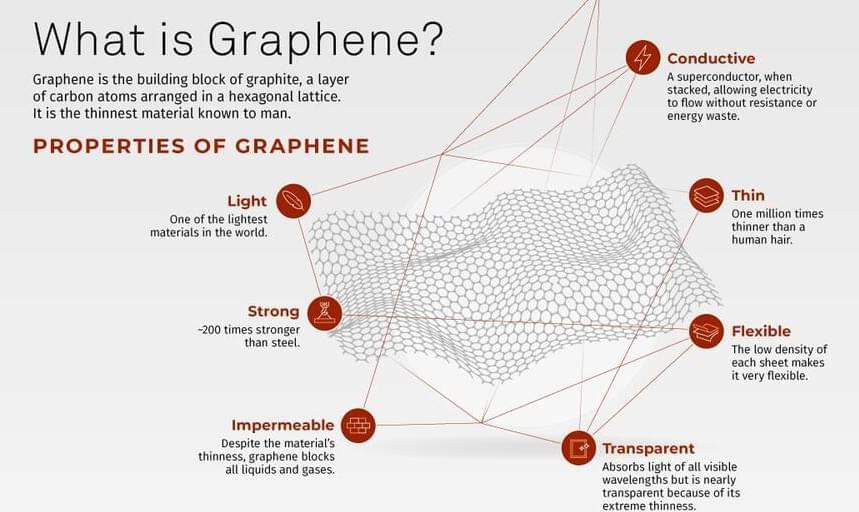

There is a new wonder material in town, and its name is graphene. Since it was first successfully isolated in 2004, graphene, with its honeycomb-like 2D structure and its wide gamut of interesting properties, has been keenly studied by material scientists.

This naturally transparent 1 millimeter thick lattice of carbon atoms has multiple applications and could even one day potentially solve the world’s water crisis.

The faith in the material is so strong that, according to numbers projected by Fortune Business Insights, its market value will be $2.8 billion in 2027.

To sign up, go to http://brilliant.org/ProRobots/ and register for free.

Also, the first 200 people who click this link will get 20% off a year’s Premium subscription.

✅ Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/pro_robots.

You are on the channel PRO Robots and in this view we present to your attention the news of high technology. Robots as people: the most realistic robot humanoid in the world, luxury patching cars of the future, xenobots — nanorobots that have learned to multiply, nanochip for reprogramming living matter, drones with legs, universal robots, robotic cleaners and other high-tech news in one video! Watch the video to the end and write in the comments, which news seemed the most interesting?

0:00 In this video.

2:25 Ameca Robot-Humanoid.

3:10 XPENG X2 flying car.

4:15 Robotic Systems Lab.

5:20 3D printed feet for drones.

6:10 Silicon nanochip for reprogramming biological tissue in living organism.

6:51 ATEA air cab.

7:23 Google unveiled its new project — Starline.

8:13 University scientists created xenobots that suddenly began to multiply.

9:06 MIRA surgical robot.

9:31 Moxi twin robots.

10:23 American startup DroneDek.

11:00 SOMATIC

11:25 Mid-range rocket — Neutron.

#prorobots #robots #robot #future technologies #robotics.

More interesting and useful content:

NASA has again delayed the multi-billion dollar James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), this time citing communications issues.

The space telescope was due to launch on December 22, 2021, from the European Spaceport in Korou, French Guiana.

The space agency is now saying “no earlier than” December 24, 2021.

The launch window closes on January 7, 2022, though opens again on January 12, 2022.

“Webb” was originally conceived in the 1990s and was first expected to launch in 2007. It had been expected to launch in March 2021, which COVID-19 delays put back to October 31 this year, then December 18 after an incident.

Designed and funded by NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), Webb is around the size of a tennis court and set to be the largest, most powerful, and most complex space science telescope ever constructed.

Its ability to detect faint infrared light will be its biggest advantage over the Hubble Space Telescope because seeing in the infrared will enable it to look much farther back in time. It’s hoped that Webb will help solve mysteries in our Solar System, closely study exoplanets and probe the structures and origins of the Universe.

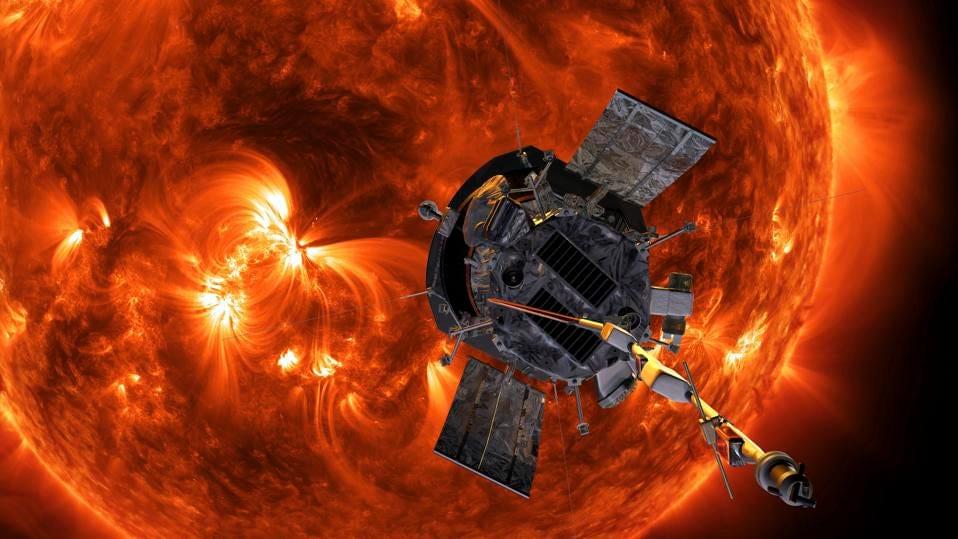

For the first time ever, a manmade object has entered the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona, which inexplicably is thousands of times hotter than our star’s surface (or photosphere).

Researchers led by a team at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor were able to predict where the Sun’s upper atmosphere began, and the probe was able to penetrate it for roughly five hours. The Parker probe was not only able to fly through the Sun’s atmosphere but was also able to sample particles and magnetic fields there, says NASA.

“Flying so close to the Sun, Parker Solar Probe now senses conditions in the magnetically dominated layer of the solar atmosphere — the corona — that we never could before,” Nour Raouafi, the Parker project scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, said in a statement. “We can actually see the spacecraft flying through coronal structures that can be observed during a total solar eclipse.”

On April 28, 2021, during its eighth flyby of the Sun, Parker Solar Probe encountered the specific magnetic and particle conditions some 8.1 million miles above the solar surface, NASA reports. That point, known as the Alfvén critical surface, marks the end of the solar atmosphere and beginning of the solar wind, says NASA.

The surface of the Sun is about 6,000 Celsius, Justin Kasper, the first author of a paper detailing the research in the journal Physical Review Letters, and a professor of climate and space sciences at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, told me. Above that, the temperature rises to more than a million degrees, he says.

Full Story:

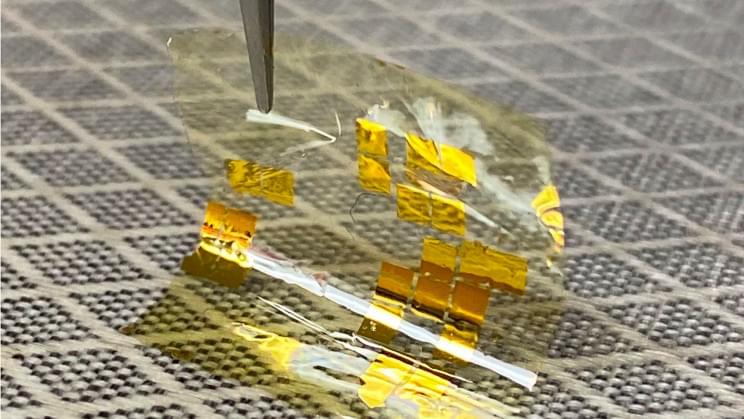

And it could work in wearables and light aircraft.

Researchers at Stanford University are developing an efficient new solar panel material that is fifteen times thinner than paper, a press statement reveals.

Made using transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), the materials have the potential to absorb a higher level of sunlight than other solar materials at the same time as providing an incredibly lightweight alternative to silicon-based solar panels.

Searching for silicon alternatives The researchers are part of a concerted effort within the scientific community to find alternative solar panel materials to silicon. Silicon is by far the most common material used for solar panels, but it’s heavy and rigid, meaning it isn’t particularly well suited to lightweight applications required for aircraft, spacecraft, electric vehicles, or even wearables.

Full Story:

And it’s likely to meet its 2024 deadline.

United Aircraft Corporation (UAC), a subsidiary of Rostec, the Russian state corporation that supports military manufacturing, has unveiled the first flight prototype of its S-70 Okhotnik combat drone, Tass reported. The unveiling that took place on Tuesday was attended by Russia’s Deputy Defense Minister, Alexey Krivoruchko.

The Okhotnik, Russian for Hunter\.