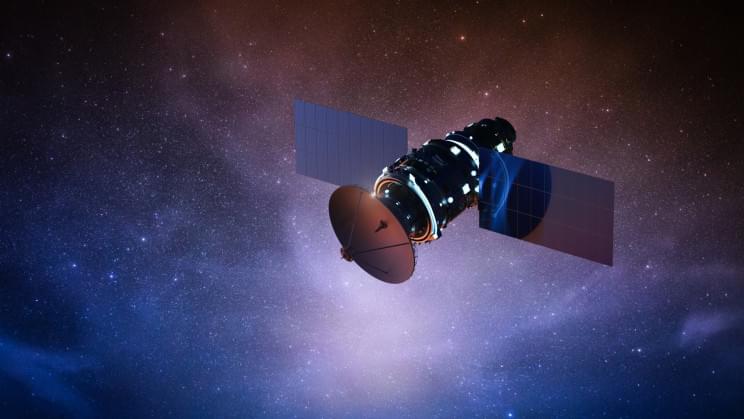

The proposed telescope would be powerful enough to detect distant planets 10 billion times fainter than their hosting star.

Astronomers have proposed a telescope that would far exceed the capabilities of Hubble.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine just released its Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics, also known as Astro 2020. The report outlines plans for the next decade of investment in astronomical equipment and projects in the U.S.

One of the real standout recommendations in the survey, DigitalTrends reports, is for a “Great Observatory” designed to replace the ailing Hubble Space Telescope, which encountered several technical problems this year due to its decades-old hardware.

Full Story: