A new wearable brain-machine interface (BMI) system could improve the quality of life for people with motor dysfunction or paralysis, even those struggling with locked-in syndrome—when a person is fully conscious but unable to move or communicate.

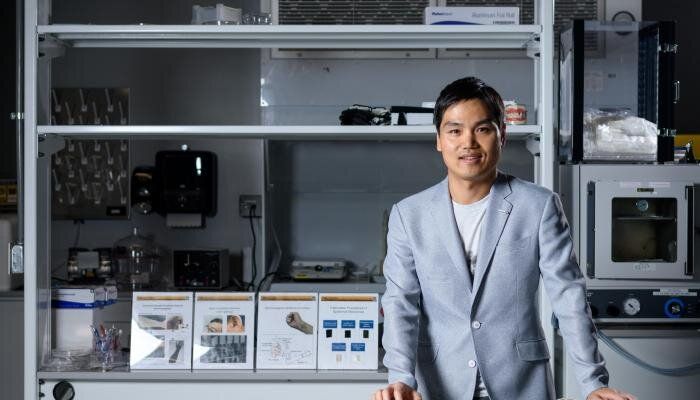

A multi-institutional, international team of researchers led by the lab of Woon-Hong Yeo at the Georgia Institute of Technology combined wireless soft scalp electronics and virtual reality in a BMI system that allows the user to imagine an action and wirelessly control a wheelchair or robotic arm.

The team, which included researchers from the University of Kent (United Kingdom) and Yonsei University (Republic of Korea), describes the new motor imagery-based BMI system this month in the journal Advanced Science.