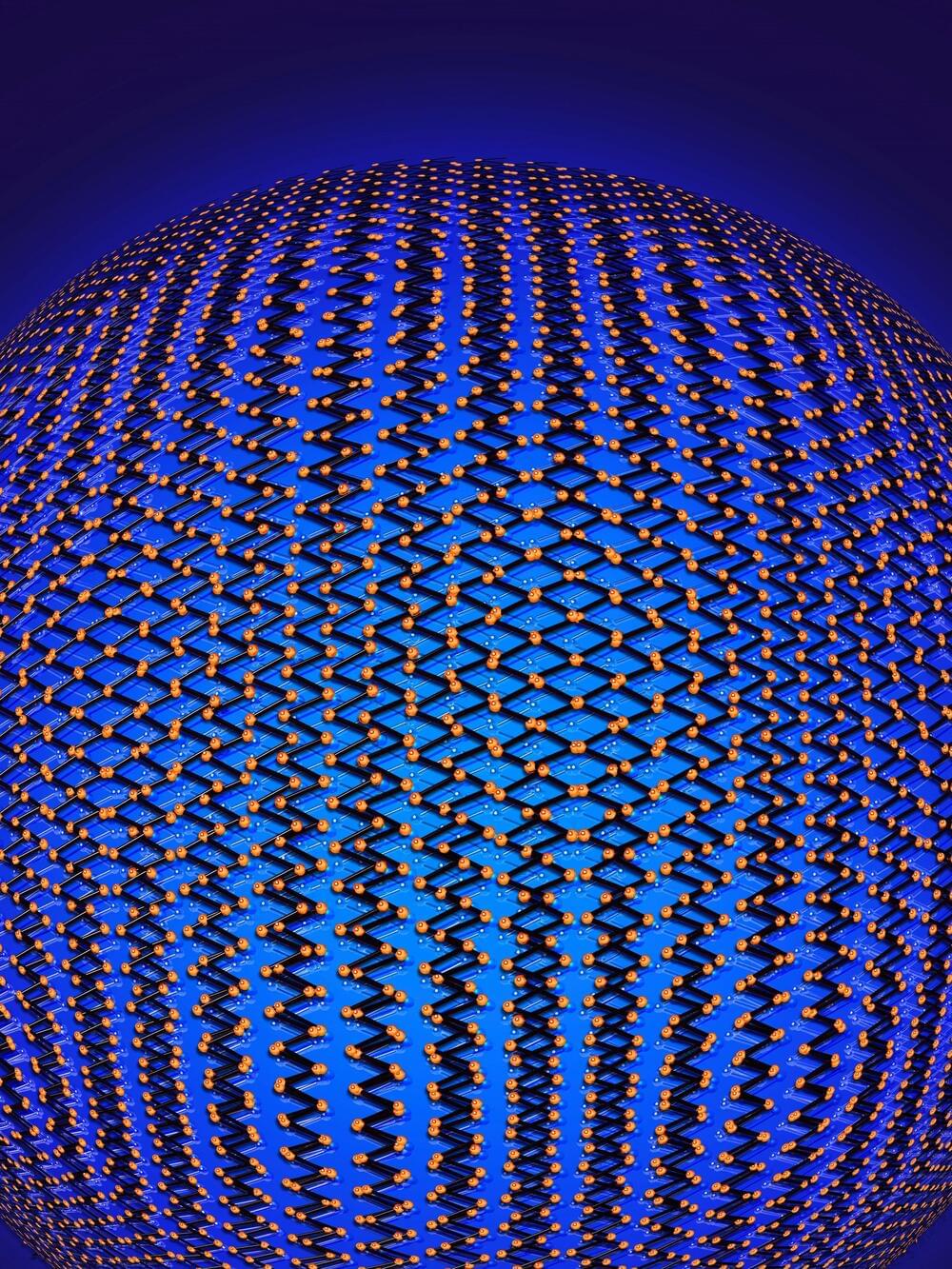

A recent experiment detailed in the journal Nature is challenging our picture of how electrons behave in quantum materials. Using stacked layers of a material called tungsten ditelluride, researchers have observed electrons in two-dimensions behaving as if they were in a single dimension—and in the process have created what the researchers assert is a new electronic state of matter.

“This is really a whole new horizon,” said Sanfeng Wu, assistant professor of physics at Princeton University and the senior author of the paper. “We were able to create a new electronic phase with this experiment—basically, a new type of metallic state.”

Our current understanding of the behavior of interacting electrons in metals can be described by a theory that works well with two-and three-dimensional systems, but breaks down when describing the interaction of electrons in a single dimension.