New ice just dropped.

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

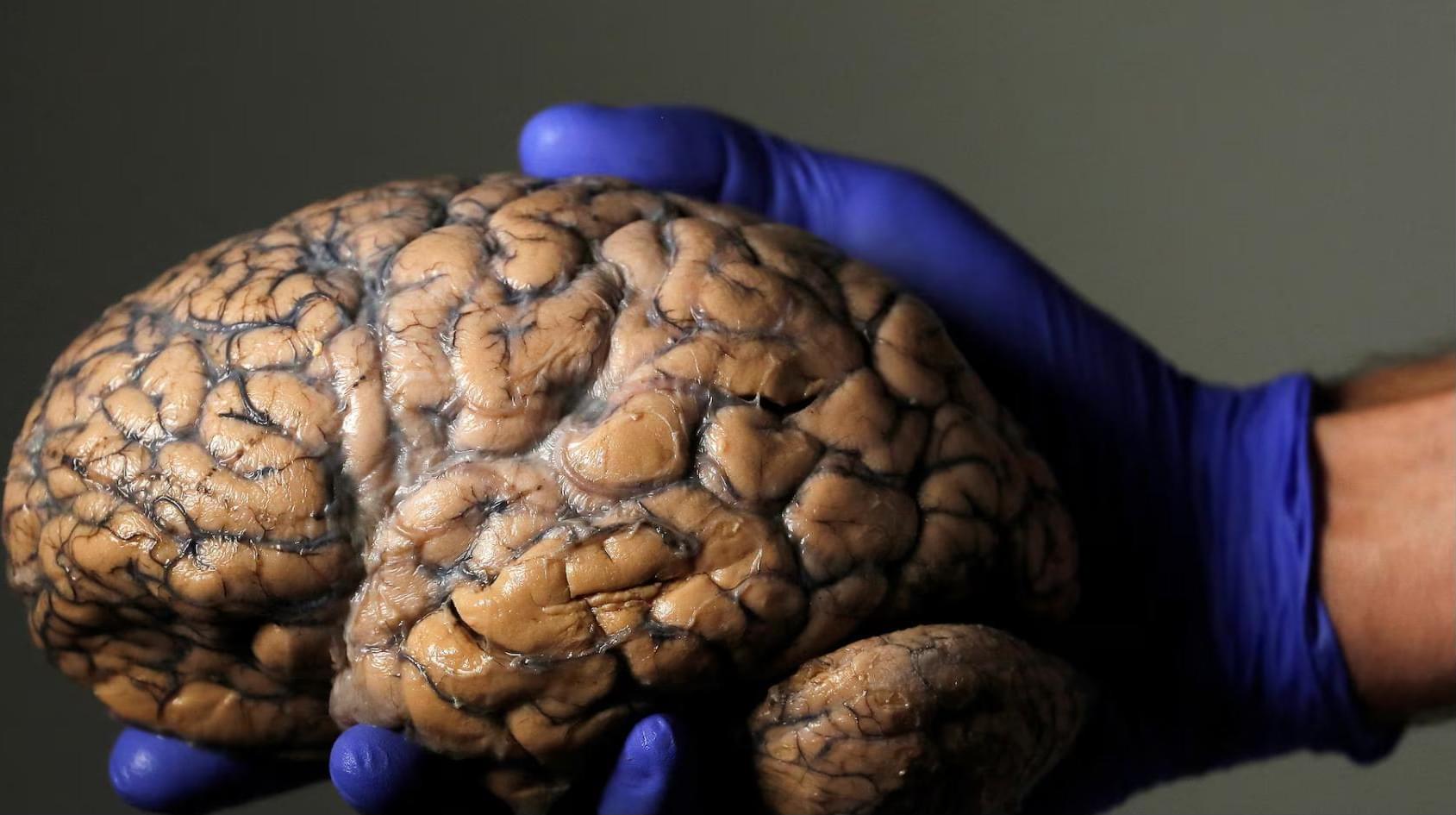

Scientists unveil first draft of atlas of the developing brain

The researchers said they have completed a first draft of atlases of the developing human brain and the developing mammalian brain.

The research focused on human and mouse brain cells, with some work in monkey brain cells too. In their initial draft, the scientists mapped the development of different types of brain cells — tracking how they are born, differentiate and mature into various types with unique functions. They also tracked how genes are turned on or off in these cells over time.

The scientists identified key genes controlling brain processes and uncovered some commonalities of brain cell development between human and animal brains, as well as some unique aspects of the human brain, including identifying previously unknown cell types.

Scientists have reached a milestone in an ambitious initiative to chart how the many types of brain cells emerge and mature from the earliest embryonic and fetal stages until adulthood, knowledge that could point to new ways of tackling certain brain-related conditions like autism and schizophrenia.

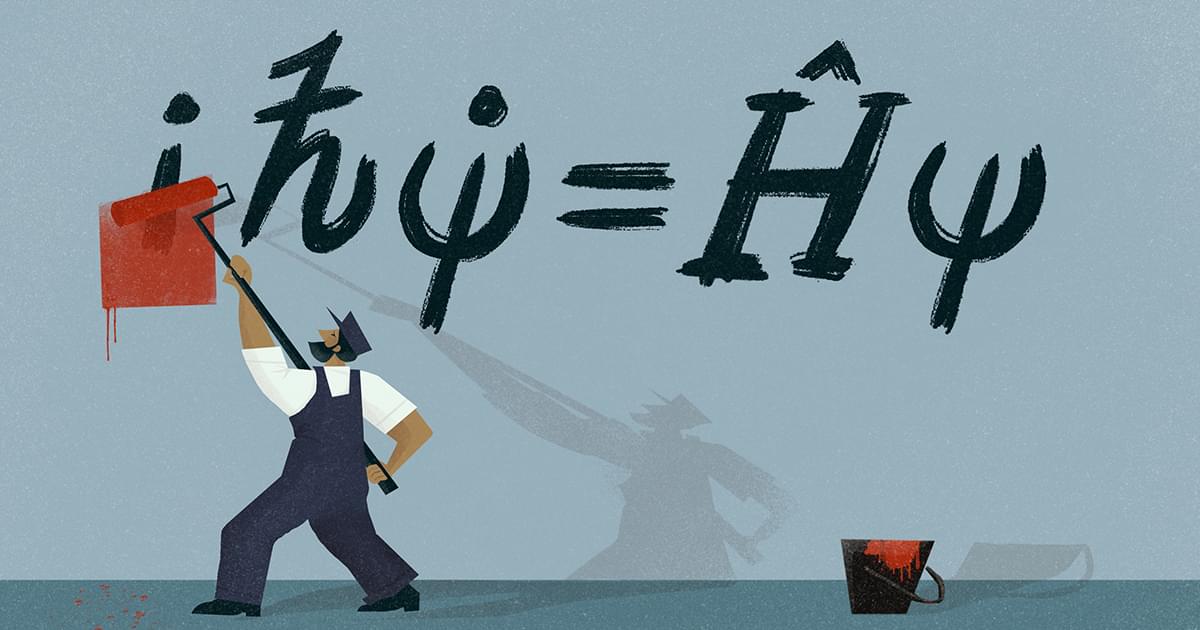

Physicists Take the Imaginary Numbers Out of Quantum Mechanics

A century ago, the strange behavior of atoms and elementary particles led physicists to formulate a new theory of nature. That theory, quantum mechanics, found immediate success, proving its worth with accurate calculations of hydrogen’s emission and absorption of light. There was, however, a snag. The central equation of quantum mechanics featured the imaginary number i, the square root of −1.

Physicists knew i was a mathematical fiction. Real physical quantities like mass and momentum never yield a negative amount when squared. Yet this unreal number that behaves as i2 = −1 seemed to sit at the heart of the quantum world.

After deriving the i-riddled equation — essentially the law of motion for quantum entities — Erwin Schrödinger expressed the hope that it would be replaced by an entirely real version. (“There is undoubtedly a certain crudeness at the moment” in the equation’s form, he wrote in 1926.) Schrödinger’s distaste notwithstanding, i stuck around, and new generations of physicists took up his equation without much concern.

SpaceX reveals simpler lander to speed up Moon return

With its metaphorical feet held over the allegorical fire by NASA, SpaceX has released a new, simplified plan to build a lander to put US astronauts back on the Moon now that the competition for the spacecraft has been reopened due to delays.

NASA’s Artemis program to establish a permanent US human presence on the Moon is ambitious beyond any doubt. However, like previous American efforts, it’s been fraught with cost overruns, delays and technical problems. One of the most aggravating of these bottlenecks has been building the lunar lander because if you don’t have a way to actually put astronauts on the actual Moon, you’re pretty much wasting your time.

SpaceX’s original plan was to build a lander based on its still-experimental Starship rocket – more than just based on it, the craft would essentially be a complete, baseline Starship complete with airfoils and heat shields. The goal was to land up to 100 tonnes of supplies on the Moon or enough to establish a complete, sustainable base.

Scientists discover creature with “all-body brain”

This is the conclusion of an international team of researchers, who found that this nervous system has a genetic organization resembling that of the brain of vertebrates, like humans.

“Our results show that animals without a conventional central nervous system can still develop a brainlike organization,” said paper author and biologist Jack Ullrich-Lüter of the Natural History Museum, Berlin, in a statement.

He added: “This fundamentally changes how we think about the evolution of complex nervous systems.”

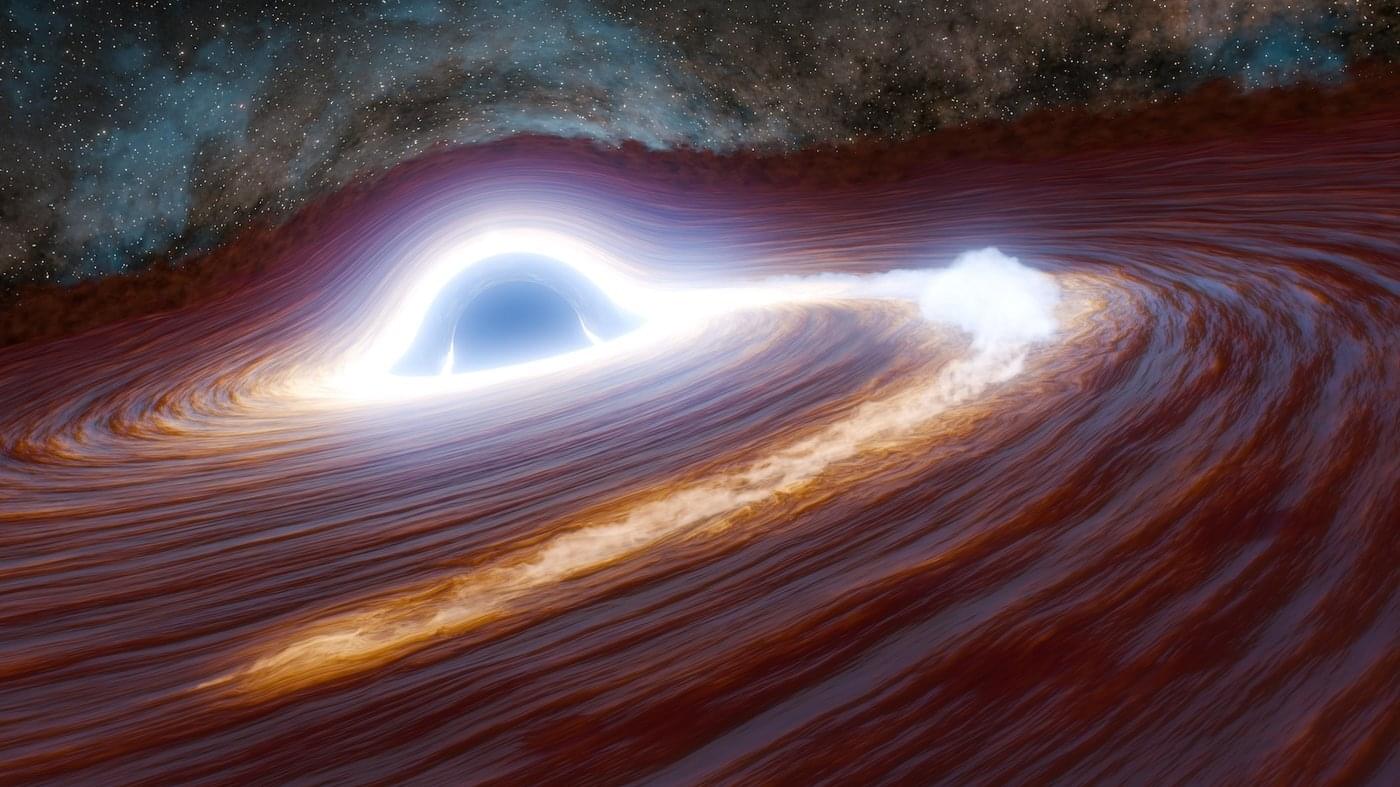

Saturday Citations: Black hole flare unprecedented; the strength of memories; bugs on the menu

This week, researchers reported finding a spider megacity in a sulfur cave on the Albania-Greece border, and experts say that you, personally, have to go live there. Economists are growing nervous about the collapse of the trillion-dollar AI bubble. And a new study links physical activity levels with the risk of digestive system cancers.

Additionally, astronomers reported the most massive and distant black hole flare ever observed; researchers determined why emotional memories are more vivid; and the scientists are once again exploring farmed insects as a food source—this time, for lengthy interplanetary missions: