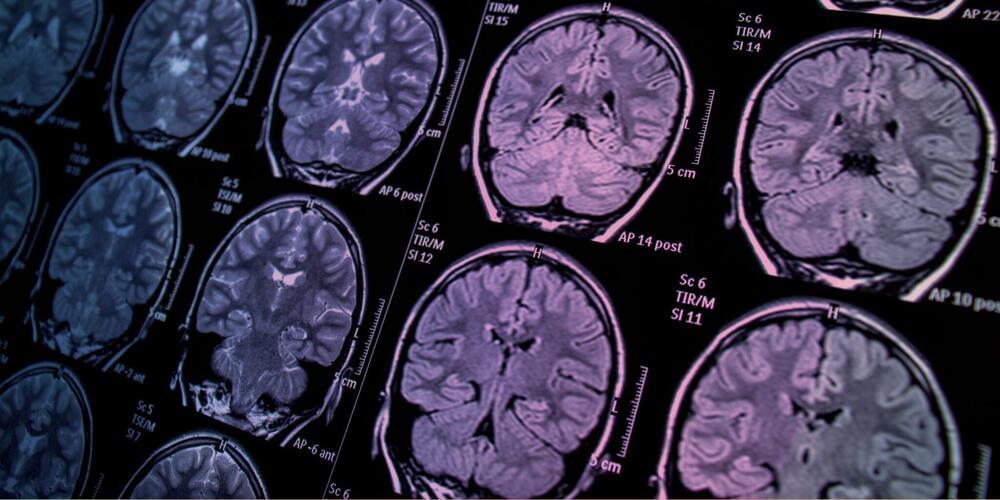

Ground-breaking research at Tel Aviv University successfully eradicated glioblastoma, a deadly form of brain cancer. The researchers achieved the result by developing a strategy based on their finding of two crucial mechanisms in the brain that promote tumor growth and survival: one shields cancer cells from the immune system, while the other provides the energy needed for rapid tumor growth. The research discovered that astrocytes, which are brain cells, regulate both methods, and that when they aren’t there, tumor cells die and are eliminated.

Rita Perelroizen, a Ph.D. student, served as the study’s lead researcher. She collaborated with Professor Eytan Ruppin of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States and was supervised by Dr. Lior Mayo of the Shmunis School of Biomedicine and Cancer Research and the Sagol School of Neuroscience at Tel Aviv. The study was recently published in the journal Brain and was highlighted with scientific commentary.