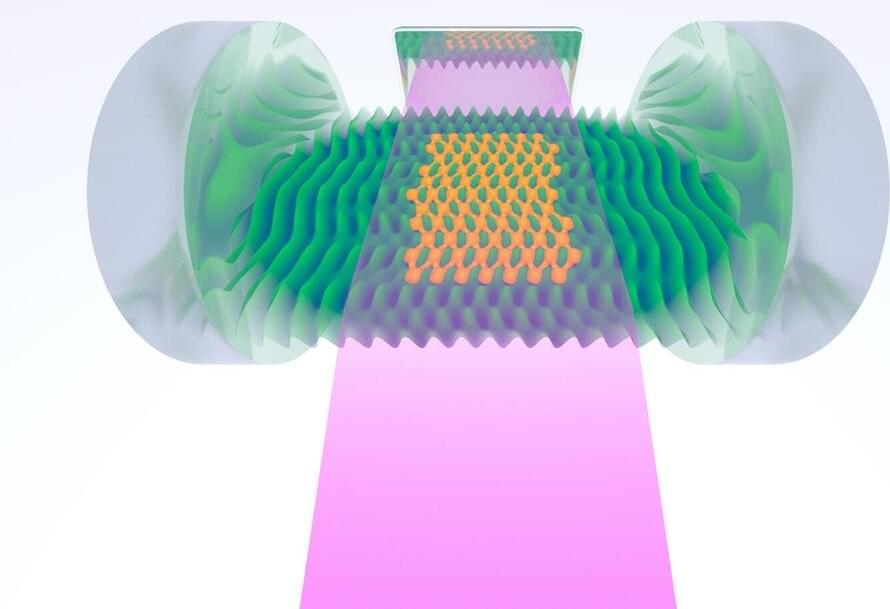

Let’s take a look at a highly abstracted neuron. It’s like a tootsie roll, with a bulbous middle section flanked by two outward-reaching wrappers. One side is the input—an intricate tree that receives signals from a previous neuron. The other is the output, blasting signals to other neurons using bubble-like ships filled with chemicals, which in turn triggers an electrical response on the receiving end.

Here’s the crux: for this entire sequence to occur, the neuron has to “spike.” If, and only if, the neuron receives a high enough level of input—a nicely built-in noise reduction mechanism—the bulbous part will generate a spike that travels down the output channels to alert the next neuron.

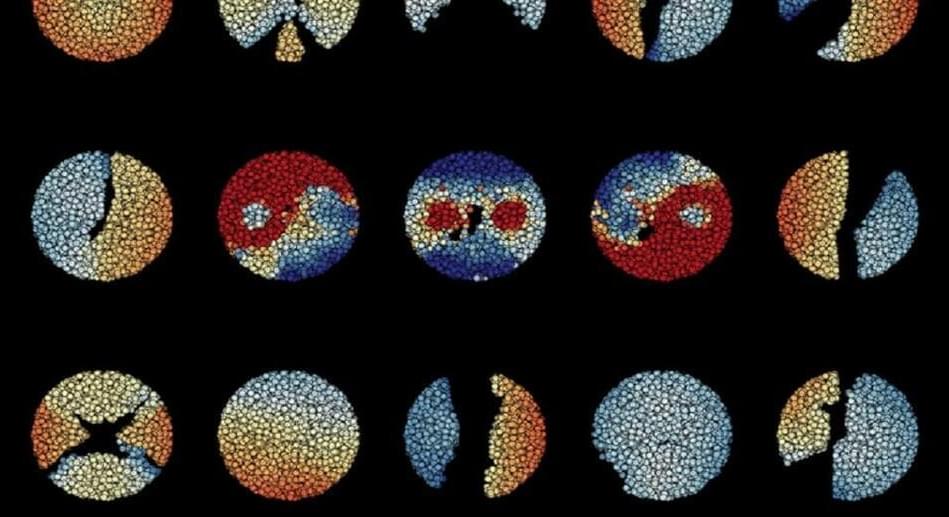

But neurons don’t just use one spike to convey information. Rather, they spike in a time sequence. Think of it like Morse Code: the timing of when an electrical burst occurs carries a wealth of data. It’s the basis for neurons wiring up into circuits and hierarchies, allowing highly energy-efficient processing.