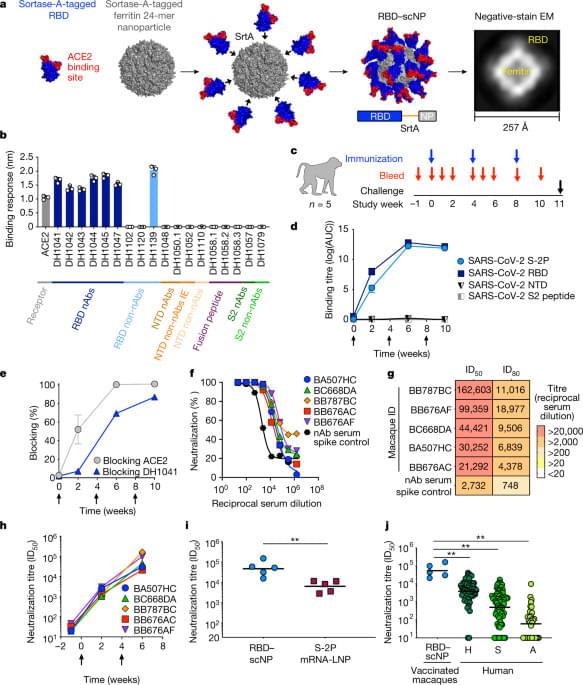

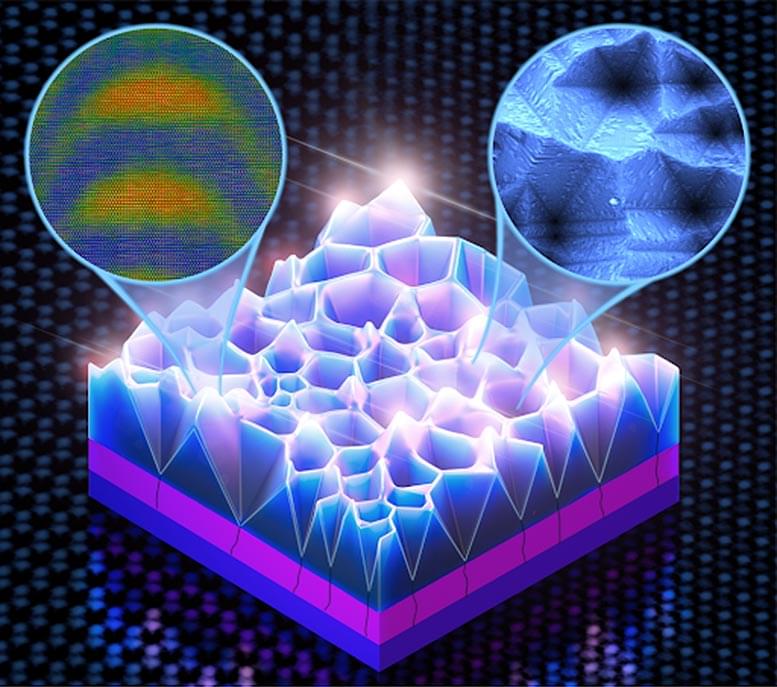

The discovery demonstrates a practical method to overcome current challenges in the manufacture of indium gallium nitride (InGaN) LEDs with considerably higher indium concentration, through the formation of quantum dots that emit long-wavelength light. The researchers have uncovered a new way t.

A type of group-III element nitride-based light-emitting diode (LED), indium gallium nitride (InGaN) LEDs were first fabricated over two decades ago in the 90s, and have since evolved to become ever smaller while growing increasingly powerful, efficient, and durable. Today, InGaN LEDs can be found across a myriad of industrial and consumer use cases, including signals & optical communication and data storage – and are critical in high-demand consumer applications such as solid state lighting, television sets, laptops, mobile devices, augmented (AR) and virtual reality (VR) solutions.

Ever-growing demand for such electronic devices has driven over two decades of research into achieving higher optical output, reliability, longevity and versatility from semiconductors – leading to the need for LEDs that can emit different colors of light. Traditionally, InGaN material has been used in modern LEDs to generate purple and blue light, with aluminum gallium indium phosphide (AlGaInP) – a different type of semiconductor – used to generate red, orange, and yellow light. This is due to InGaN’s poor performance in the red and amber spectrum caused by a reduction in efficiency as a result of higher levels of indium required.

In addition, such InGaN LEDs with considerably high indium concentrations remain difficult to manufacture using conventional semiconductor structures. As such, the realization of fully solid-state white-light-emitting devices – which require all three primary colors of light – remains an unattained goal.