Elon Musk joins Vladimir Putin’s growing list of American puppets by parroting the Russian leader’s demands for appeasement.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=Pr5aRhEIE9A&feature=share

Researchers from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) claimed in a recently published study to have developed a gene editing method that is supposed to be “more efficient and safer” than the technique used so far.

But there is a lot behind gene editing, so let’s look at what it is all about and its risks and applications.

—————————

#ChinaRevealed #ChinaNews

Tesla is considering several sites in Canada for its next Gigafactory according to reports. This comes as Francois-Philippe Champagne, Canada’s industry and innovation minister, recently confirmed talks with Tesla over a new factory. He stated the following (via Reuters):

“Yes, I’m talking to them,” Champagne said, in response to a question about reports of Tesla looking to build a factory in Canada. “I’m talking also to all the automakers around the world.”

Tesla CEO Elon Musk has hinted at a Canadian Gigafactory on numerous occasions, most recently at the automaker’s annual shareholders’ meeting last month. And now reports from Canada suggest representatives from Tesla have already visited numerous locations in Ontario and Quebec. Moreover, Tesla is currently looking for a high-volume recruiter in the Quebec area, indicating the automaker could be on the verge of hiring several thousand Canadian workers.

An artificial intelligence created by the firm DeepMind has discovered a new way to multiply numbers, the first such advance in over 50 years. The find could boost some computation speeds by up to 20 per cent, as a range of software relies on carrying out the task at great scale.

Matrix multiplication – where two grids of numbers are multiplied together – is a fundamental computing task used in virtually all software to some extent, but particularly so in graphics, AI and scientific simulations. Even a small improvement in the efficiency of these algorithms could bring large performance gains, or significant energy savings.

The biggest number in the world Agnijo Banerjee at New Scientist Live this October.

Russia had banned Facebook and Instagram in March after accusing their parent company of tolerating ‘Russophobia’.

UW Medicine researchers have found that algorithms are as good as trained human evaluators at identifying red-flag language in text messages from people with serious mental illness. This opens a promising area of study that could help with psychiatry training and scarcity of care.

The findings were published in late September in the journal Psychiatric Services.

Text messages are increasingly part of mental health care and evaluation, but these remote psychiatric interventions can lack the emotional reference points that therapists use to navigate in-person conversations with patients.

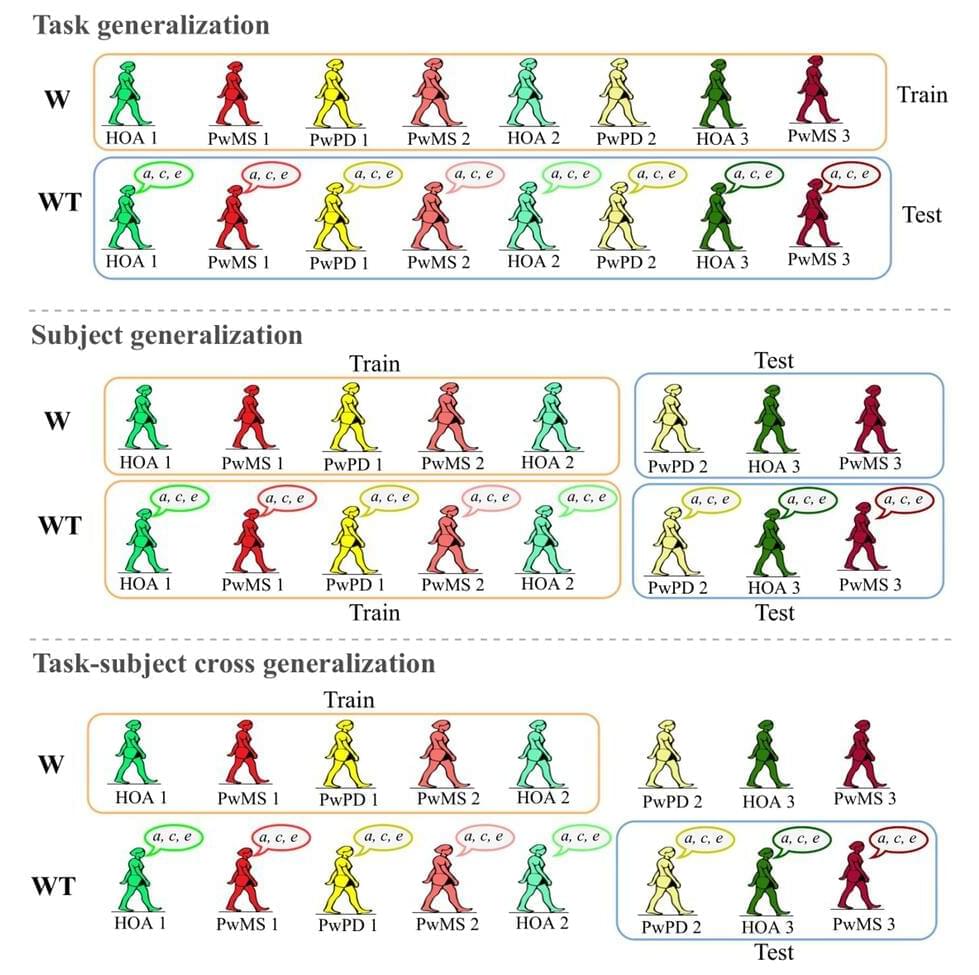

In an effort to streamline the process of diagnosing patients with multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease, researchers used digital cameras to capture changes in gait—a symptom of these diseases—and developed a machine-learning algorithm that can differentiate those with MS and PD from people without those neurological conditions.

Their findings are reported in the IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics.

The goal of the research was to make the process of diagnosing these diseases more accessible, said Manuel Hernandez, a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign professor of kinesiology and community health who led the work with graduate student Rachneet Kaur and industrial and enterprise systems engineering and mathematics professor Richard Sowers.

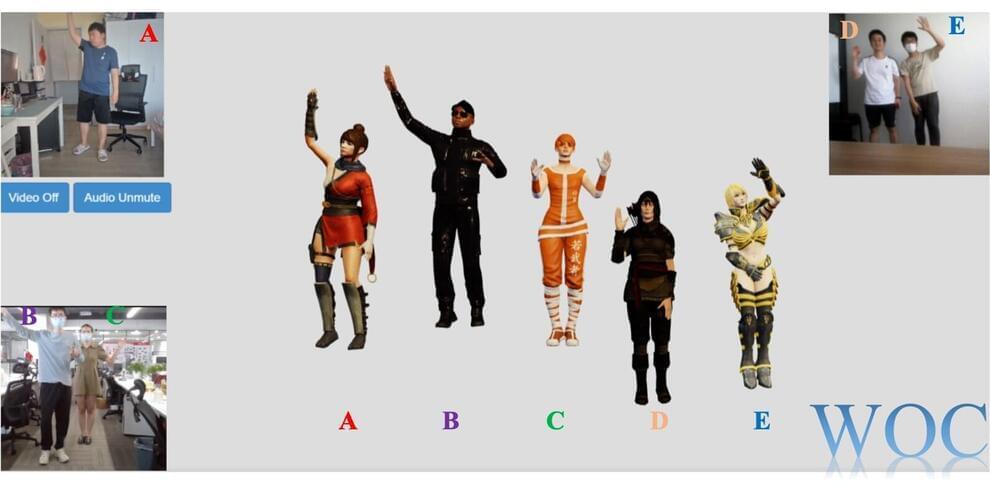

In the past few years, a growing number of computer scientists have been exploring the idea of “metaverse,” an internet-based space where people would be able to virtually perform various everyday activities. The general idea is that, using virtual reality (VR) headsets or other technologies, people might be able to attend work meetings, meet friends, shop, attend events, or visit places, all within a 3D virtual environment.

While the metaverse has recently been the topic of much debate, accessing its 3D “virtual environments” often requires the use of expensive gear and devices, which can only be purchased by a relatively small amount of people. This unavoidably limits who might be able to access this virtual space.

Researchers at Beijing Institute of Technology and JD Explore Academy have recently created WOC, a 3D online chatroom that could be accessible to a broader range of people worldwide. To gain access to this chatroom, which was introduced in a paper pre-published on arXiv, users merely need a simple computer webcam or smartphone camera.