Advancements in 3D printing have made it easier for designers and engineers to customize projects, create physical prototypes at different scales, and produce structures that can’t be made with more traditional manufacturing techniques. But the technology still faces limitations—the process is slow and requires specific materials which, for the most part, must be used one at a time.

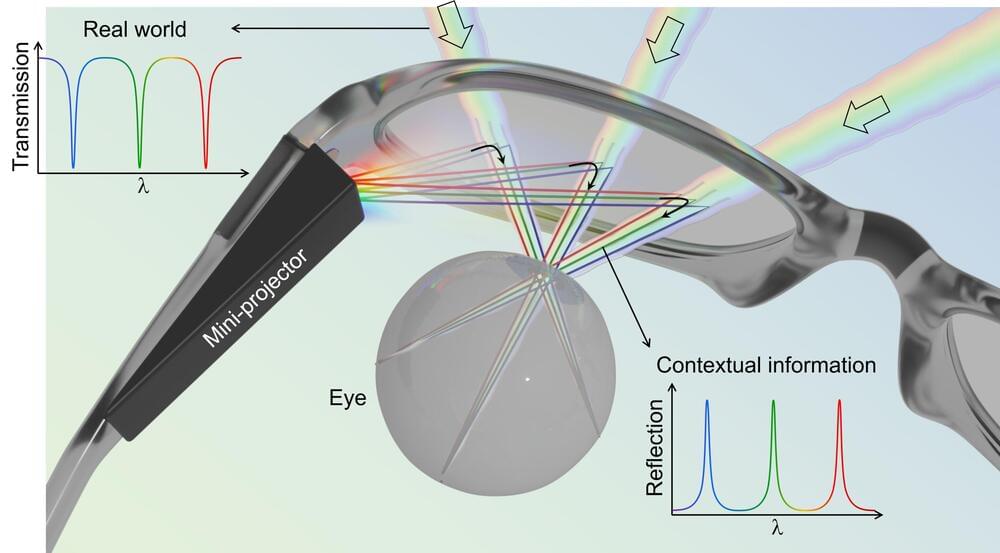

Researchers at Stanford have developed a method of 3D printing that promises to create prints faster, using multiple types of resin in a single object. Their design, published recently in Science Advances, is 5 to 10 times faster than the quickest high-resolution printing method currently available and could potentially allow researchers to use thicker resins with better mechanical and electrical properties.

“This new technology will help to fully realize the potential of 3D printing,” says Joseph DeSimone, the Sanjiv Sam Gambhir Professor in Translational Medicine and professor of radiology and of chemical engineering at Stanford and corresponding author on the paper. “It will allow us to print much faster, helping to usher in a new era of digital manufacturing, as well as to enable the fabrication of complex, multi-material objects in a single step.”