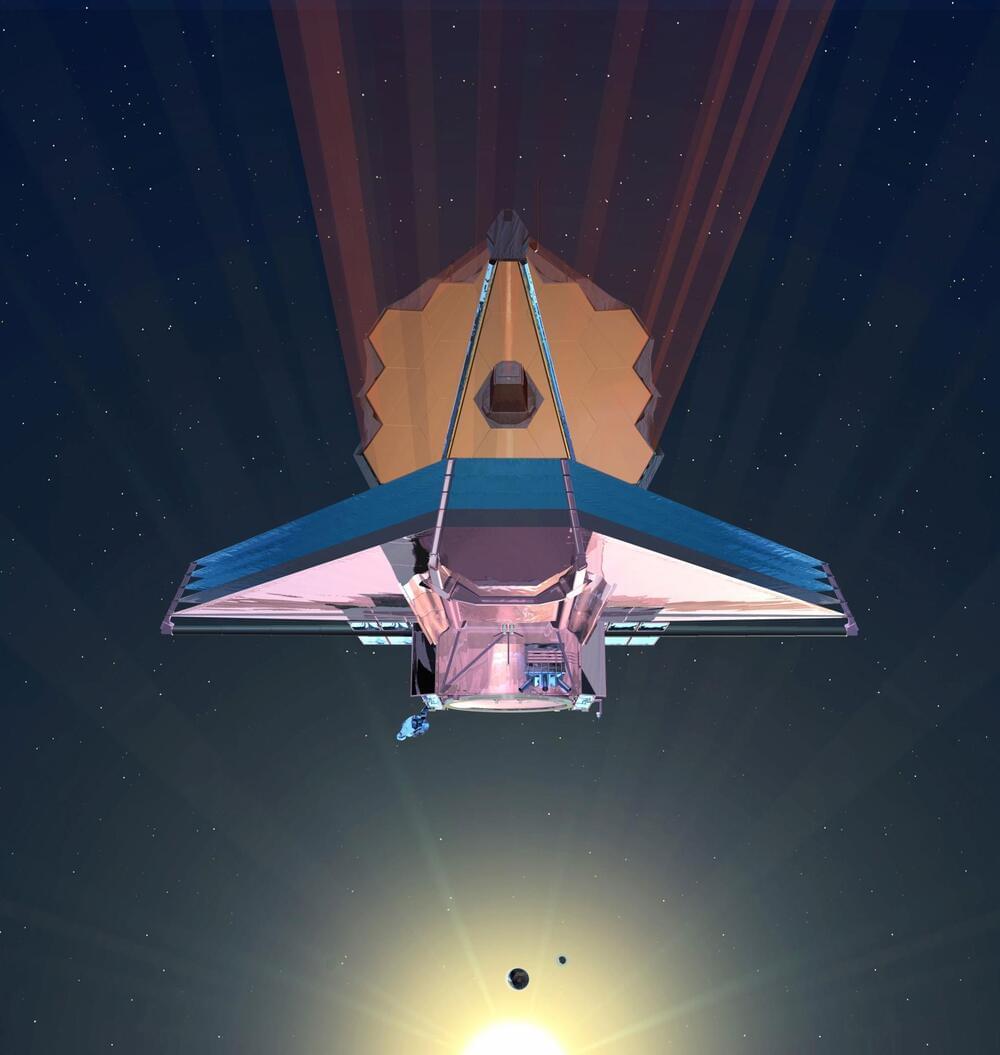

The deal will involve SpaceX installing ground stations inside google’s data centers to link with Starlink satellites. This synergy will provide ultra-fast internet services to enterprise clients. We could start seeing the outcome of the partnership as early as this year, especially since Musk has promised Starlink would exit beta mode despite the size of googling this deal is enormous because it is giving an edge in its competition the software behemoth Microsoft and online retail king Amazon in the cloud computing market.

Google needs to diversify as quickly as possible because its advert business is no longer growing at the usual rate. The cloud is a way for Google to shore up its revenue to sustain its growth, so landing a client like SpaceX is a big deal for Google because its cloud computing service will be delivered to clients at high speed the first at Google data center to host a starling the base station is in New Albany Ohio followed by other data centers in the US. Still, ultimately most of google’s data centers worldwide would be connected.

Google and SpaceX had a bit of history back in 2015; the search giant invested 900 million dollars into SpaceX, which was meant to cover various technologies, including making the satellites themselves. Hence, it is natural that the two companies would do business together. The deal benefits all the parties involved, and Google brings its cloud services to more customers through a secure and fast internet network.