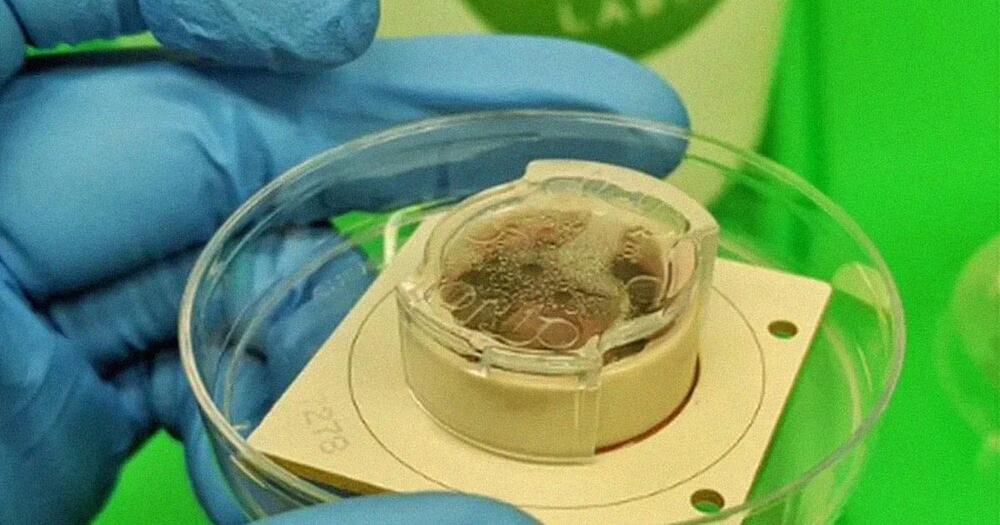

MR1805/iStock.

The study was published in Nature Astronomy, and it details how simple microbes that fed on hydrogen and excreted methane were likely abundant on Mars roughly 3.7 billion years ago. This was at approximately the same time that the earliest life was forming in Earth’s oceans.