An actual ethicist thinks that we might get a Terminator future soon if we keep making AI too advanced.

Interested in using Experimenter for your research? Contact us at [email protected]

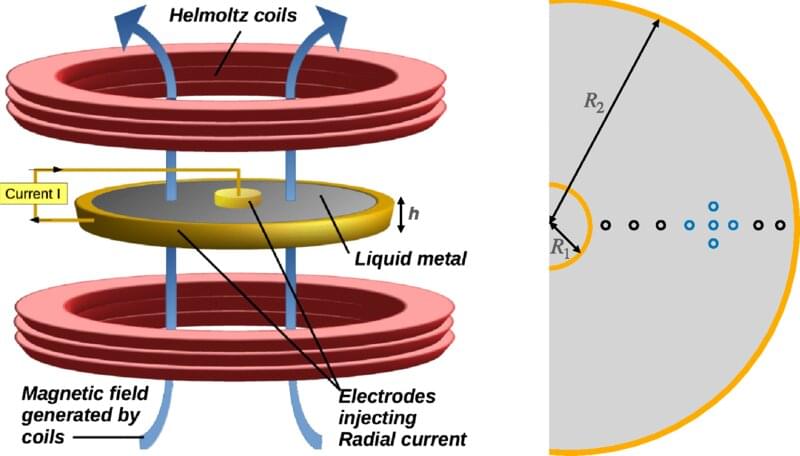

A team of researchers at the Sorbonne University of Paris reports a new way to emulate black hole and stellar accretion disks. In their paper published in the journal Physical Review Letters, the group describes using magnetic and electric fields to create a rotating disk made of liquid metal to emulate the behavior of material surrounding black holes and stars, which leads to the development of accretion disks.

Prior research has shown that massive objects have a gravitational reach that pulls in gas, dust and other material. And since such massive objects tend to spin, the material they pull in tends to swirl around the object as it moves closer. When that happens, gravity exerted by materials in the swirling mass tends to coalesce, resulting in an accretion disk. Astrophysicists have been studying the dynamics of accretion disks for many years but have not been able to figure out how angular momentum is transferred from the inner parts of a given accretion disk to its outer parts as material in the disk moves ever closer to the central object.

Methods used to study accretion disks have involved the development of math formulas, computer simulations and real-world models using liquids that swirl like eddies. None of the approaches has proven suitable, however, which has led researchers to look for new models. In this new effort, the researchers developed a method to generate an accretion disk made of liquid metal bits spinning in the air.

Although plant-based polylactic acid (PLA) bioplastic is acclaimed for its biodegradability, it can take quite a long time to degrade if the conditions aren’t quite right. Bearing this fact in mind, Washington State University scientists have devised a way of upcycling it into a 3D-printing resin.

“[PLA] is biodegradable and compostable, but once you look into it, it turns out that it can take up to 100 years for it to decompose in a landfill,” said postdoctoral researcher Yu-Chung Chang, co-corresponding author of the study. “In reality, it still creates a lot of pollution. We want to make sure that when we do start producing PLA on the million-tons scale, we will know how to deal with it.”

To that end, Chang and colleagues developed a process in which an inexpensive chemical known as aminoethanol is used to break down the long chains of molecules that make up PLA. Those chains are rendered into simple monomers, which are the basic building blocks of plastic. The process takes about two days, and can be carried out at mild temperatures.

CAMDEN, N.J., August 30, 2022 – NFI, a leading supply chain solutions provider, today announced it has signed a $10 million agreement to deploy Boston Dynamics’ newest robot, Stretch, across its U.S. warehousing operations. The mobile robot will begin unloading trucks and containers as a pilot program at NFI’s Savannah, GA facility in 2023, with plans to outfit additional warehouse locations across North America over the next few years.

Supply chain demand remains near all-time highs. To support the flow of goods and increase operational capacity, NFI continues to invest in technology that supports a people-led, technology-enabled approach. The investment also falls in line with NFI’s Applied Innovation focus, which pilots new technologies to demonstrate a real-world application within operations before scaling across its North American network.

“At a time when companies need to evolve to meet consumer expectations, NFI has stepped in as the innovative logistics partner, contributing to our customers’ competitive edge,” said Sid Brown, CEO of NFI. “Our innovation portfolio emphasizes productivity and safety in NFI’s operations. With Stretch, we will enhance the movement of freight through our facilities while providing a safer environment for our employees.”

Even had the same name.

https://tmp2.fandom.com/wiki/Modular_Unmanned_Orbital_Laboratory_-_MUOL

https://tmp2.fandom.com/wiki/Telerobotic_Outpost.

Originally

Developed as part of the Modular Unmanned Orbital Laboratory — MUOL program early in the Asgard phase, Inchworm telerobots are likely to become the most common form of workhorse utility robot throughout TMP. Deriving from the simple robotic arms employed by later generation space agency spacecraft and orbital outposts, employ a very simple architecture to the utmost in multi-purpose flexibility. An Inchworm is a simple robot consisting of a single mechanical arm equipped with at least three two-axis electric-powered joints; two at end-effector units and others at intervals in-between. Unlike simpler arm robots, the end-effector units at both ends of the Inchworm feature small stereo cameras, LED lights, and a modular quick-connect interface including bus interfaces for power and communication. The Inchworm needs no internal power supplies, relying entirely on power through its end-effector bus connectors and plug-in anchor point grid, though out would be able to carry independent power sources in mobile anchor units. These end effector units are intended to serve alternately as tool-heads and anchor points, thus allowing the robot to traverse a grid of anchor sockets by traveling end-over-end while simultaneously carrying a pallet of modular tools. In addition, sections of the Inchworm arms may optionally include telescoping linear actuators allowing them to expand or contract in length –though the use of this would often depend on load bearing capacities of such mechanisms. would also be able to link end-to-end to create composite robots of greater length, their joints optionally including a lock-pin system to rigidize them in a given position. Originally intended for simple remote control or teleoperation, would also be easily employed with fully automated control based on centralized computers, allowing them to be used in coordinated groups and task/production lines or to off-load certain amounts of their control to overcome limitations in manual communications latency. This would afford them increasing autonomous capability in proportion to this centralized and networked computer intelligence but still allow for direct manual control on demand.

Aug 31 (Reuters) — Chip designer Nvidia Corp (NVDA.O) said on Wednesday that U.S. officials told it to stop exporting two top computing chips for artificial intelligence work to China, a move that could cripple Chinese firms’ ability to carry out advanced work like image recognition and hamper Nvidia’s business in China.

Nvidia shares fell 6.6% after hours. The company said the ban, which affects its A100 and H100 chips designed to speed up machine learning tasks, could interfere with completion of developing the H100, the flagship chip Nvidia announced this year.

Shares of Nvidia rival Advanced Micro Devices Inc (AMD.O) fell 3.7% after hours. An AMD spokesman told Reuters the company had received new license requirements that will stop its MI250 artificial intelligence chips from being exported to China but it believes its MI100 chips will not be affected. AMD said it does not believe the new rules will have a material impact on its business.