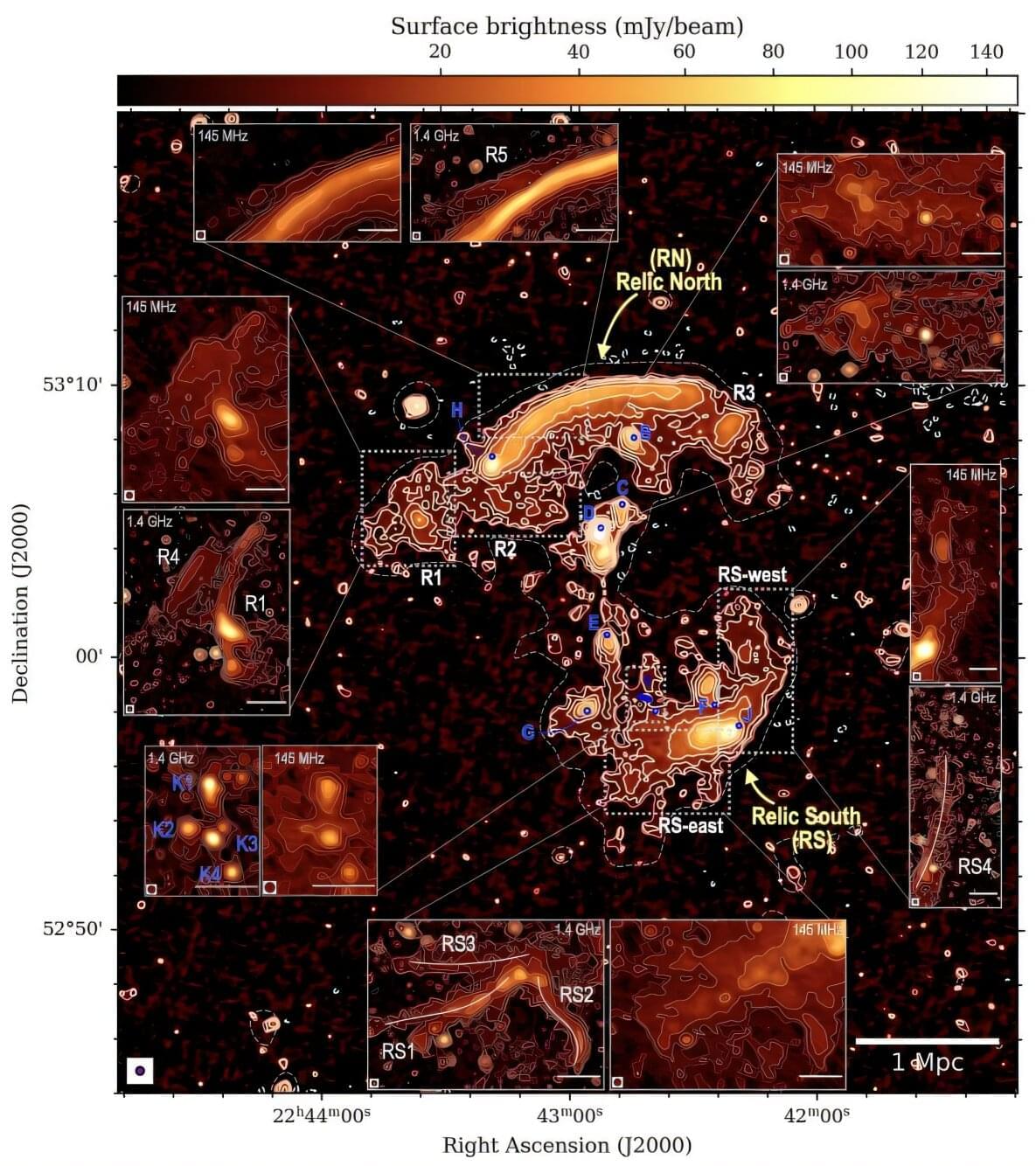

Using the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR), European astronomers have investigated a galaxy cluster designated CIZA J2242.8+5301, dubbed the Sausage cluster. The observations conducted at very low radio frequencies provide more insights into the properties of radio relics in this cluster. The new findings are presented in a research paper published May 29 on the arXiv preprint server.

Galaxy clusters consist of up to thousands of galaxies bound together by gravity. They are the largest known gravitationally-bound structures in the universe, and therefore serve as excellent laboratories for studying galaxy evolution and cosmology. Observations show that galaxy clusters generally form as a result of mergers and grow by accreting sub-clusters.

CIZA J2242.8+5301 is a well-studied merging galaxy cluster at a redshift of 0.192. It contains prominent double radio relics (diffuse, elongated radio sources of synchrotron origin) and other diffuse radio sources. CIZA J2242.8+5301 was nicknamed the Sausage cluster due to the distinctive morphology of its northern relic.