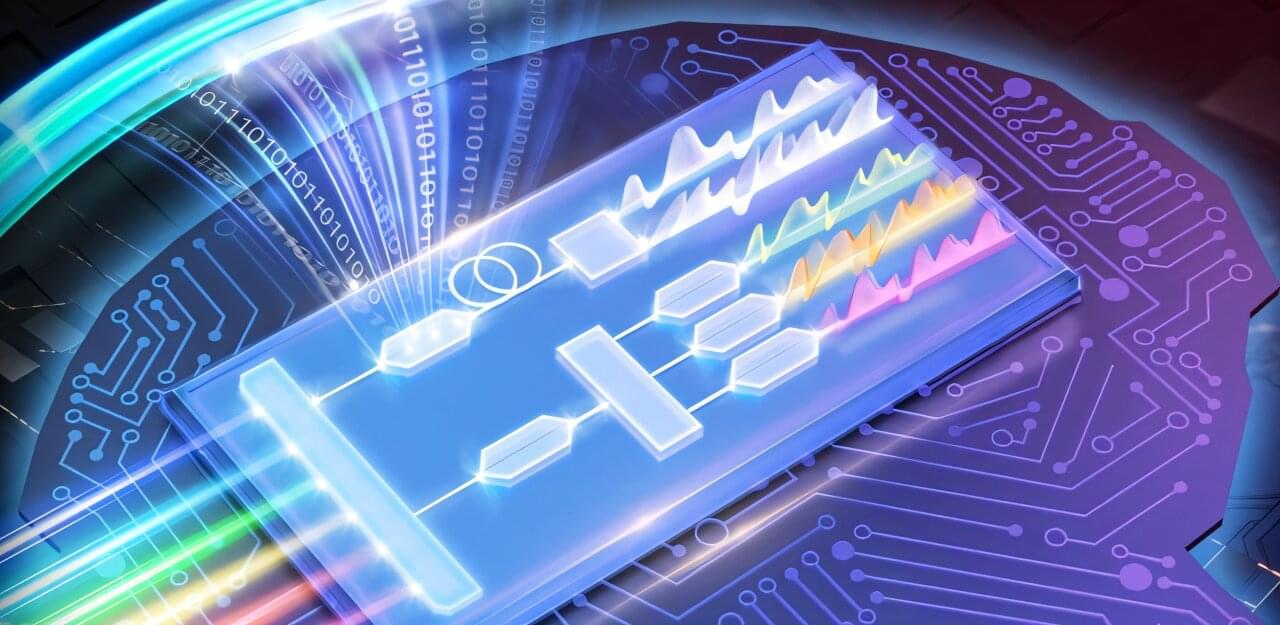

Distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) systems represent cutting-edge technology in infrastructure monitoring, capable of detecting minute vibrations along fiber optic cables spanning tens of kilometers. These systems have proven invaluable for applications ranging from earthquake detection and oil exploration to railway monitoring and submarine cable surveillance.

However, the massive amounts of data generated by these systems create a significant bottleneck in processing speed, limiting their effectiveness for real-time applications where immediate responses are crucial.

Machine learning techniques, particularly neural networks, have emerged as a promising solution for processing DAS data more efficiently. While the processing capabilities of traditional electronic computing using CPUs and GPUs have massively improved over the past decades, they still face fundamental limitations in speed and energy efficiency. In contrast, photonic neural networks, which use light instead of electricity for computations, offer a revolutionary alternative, potentially achieving much higher processing speeds at a fraction of the power.