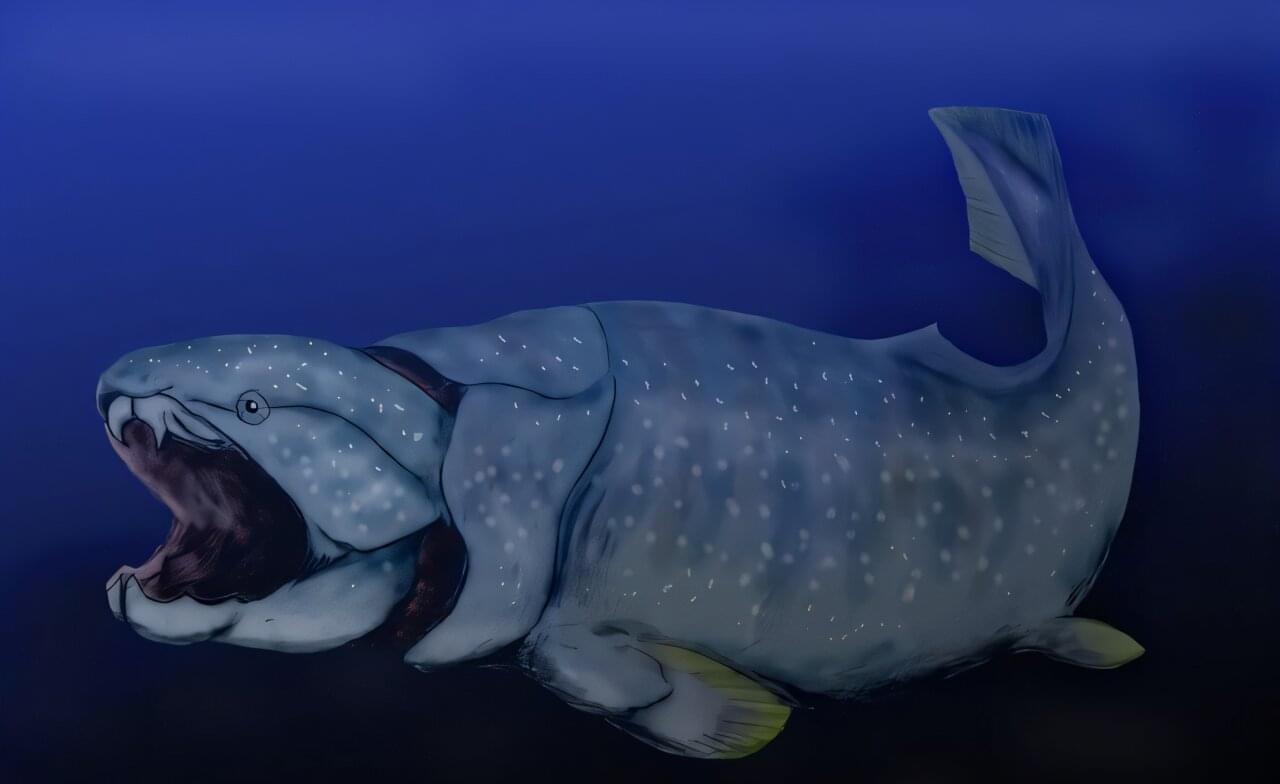

Some 390 million years ago in the ancient ocean, marine animals began colonizing depths previously uninhabited. New research indicates this underwater migration occurred in response to a permanent increase in deep-ocean oxygen, driven by the above-ground spread of woody plants—precursors to Earth’s first forests.

That rise in oxygen coincided with a period of remarkable diversification among fish with jaws—the ancestors of most vertebrates alive today. The finding suggests that oxygenation might have shaped evolutionary patterns among prehistoric species.

The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.