Predictions across the field range from a few months to a few decades, but experts agree—change is coming.

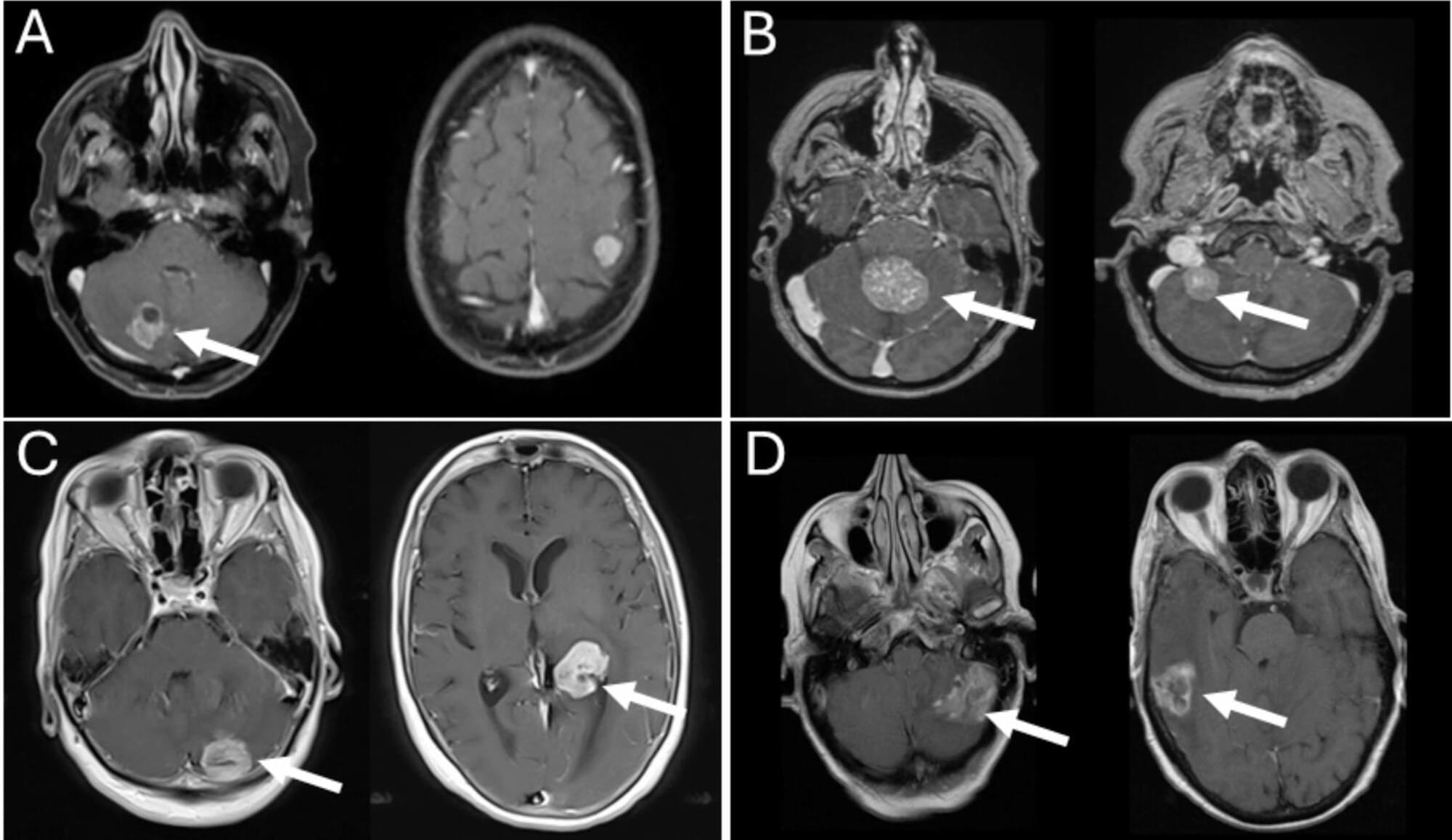

Surgical treatment of multiple breast cancer brain metastases: clinical characteristics and factors impacting postoperative survival

Posted in biotech/medical, neuroscience | Leave a Comment on Surgical treatment of multiple breast cancer brain metastases: clinical characteristics and factors impacting postoperative survival

Purpose Breast cancer (BC) is one of the most common primary tumor entities that develop brain metastases (BM) during disease progression. Multiple BM are associated with poorer prognosis, but various surgical, radiotherapeutic and systemic treatment approaches improve survival. We aimed to identify prognostic factors and evaluate the overall survival following BM surgery in patients with multiple BCBM. Methods All metachronous metastasized female patients with resected BCBM at our institution between 2008 and 2019 were included. Data on clinical, radiologic, and histopathologic parameters were recorded and analyzed using univariate and multivariate regression models. Results Among the 93 patients included in the final analysis, 30 individuals presented with multiple BM. Compared to patients with single BM, those with multiple BM were more likely to have infratentorial BM (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 3.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03–10.83, p = 0.044), HER2(human epidermal growth factor receptor 2)-positive BC (aOR 3.93, 95% CI 1.23–12.53, p = 0.021) and hepatic metastases (aOR 5.86, 95% CI 1.34–25.61, p = 0.019). There was no significant difference in postoperative survival between individuals with multiple (median: 12.5 months) and single BM (17.0 months, p = 0.186). In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, adjuvant radiotherapy (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 5.93, 95% CI 1.06–33.26, p = 0.043) and trastuzumab treatment (aHR 4.95, 95% CI 1.72–14.25, p = 0.003) were associated with longer postoperative survival multiple BCBM patients. Conclusion BC patients with multiple BM show remarkable postoperative survival, particularly if combined with adjuvant radiotherapy. Our data justify the surgery of multiple BCBM in patients with appropriate clinical condition and feasible location of BM.

A University of Nebraska–Lincoln engineering team is another step closer to developing soft robotics and wearable systems that mimic the ability of human and plant skin to detect and self-heal injuries.

Engineer Eric Markvicka, along with graduate students Ethan Krings and Patrick McManigal, recently presented a paper at the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation in Atlanta, Georgia, that sets forth a systems-level approach for a soft robotics technology that can identify damage from a puncture or extreme pressure, pinpoint its location and autonomously initiate self-repair.

The paper was among the 39 of 1,606 submissions selected as an ICRA 2025 Best Paper Award finalist. It was also a finalist for the Best Student Paper Award and in the mechanism and design category.

The refillable eye implants continuously deliver a customised formulation of a drug over a period of several months.

The GHZ paradox was introduced in 1989. It highlights the mismatch between classical viewpoints and the quantum description of reality.

Sodium–air fuel cells could unlock electric flight and clean transit, capturing CO₂ and outperforming lithium batteries.

Learn how to increase testosterone naturally with 8 proven biohacks. Backed by science, optimized for energy, strength, and mood. No meds. No fluff.

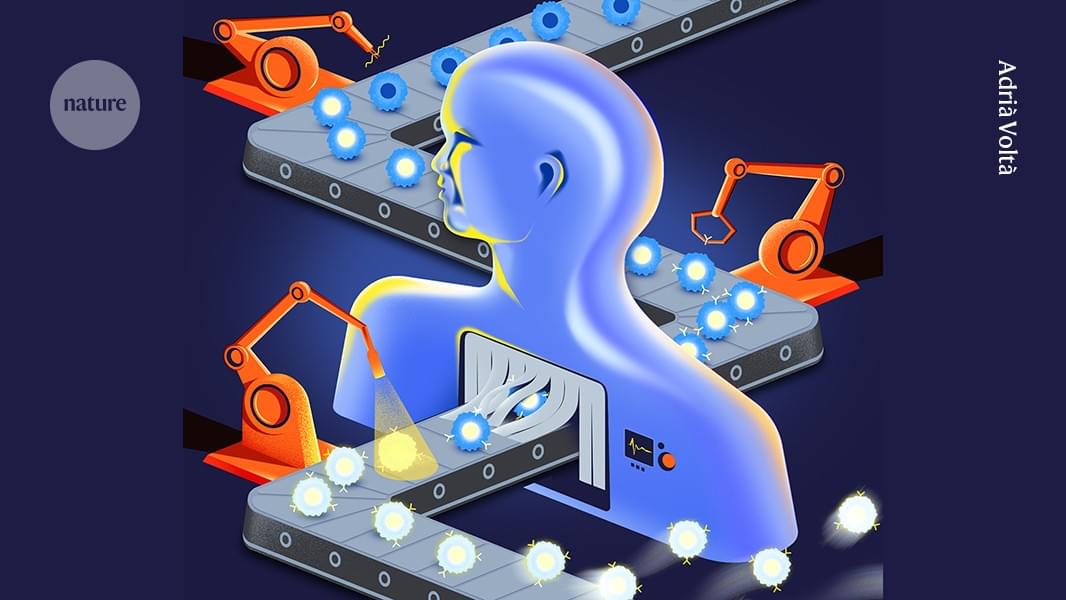

Manufacturing CAR T cells in the laboratory is expensive and time-consuming. An in vivo approach could get the powerful therapy to more people.

Join Territory: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC8SGU9hQEaJpsLuggAhS90Q/join.

Research paper: https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/538/1/76/8019798?login=false.

The James Webb Space Telescope has revealed ancient galaxies that appear far too massive and mature for their age, challenging our current understanding of cosmic evolution. These galaxies, observed just 330 million years after the Big Bang, should be small and irregular. Instead, they are well-formed and massive, suggesting that something fundamental about our models of the early universe may be incomplete.

One radical theory proposes that our universe could be the interior of a black hole in a larger parent universe. In this model, the Big Bang was not an explosion in empty space but the moment matter collapsed into a black hole, creating a new cosmos inside. The event horizon of this black hole would act as a boundary, beyond which everything—including time—behaves differently from an outside perspective.

Recent observations also suggest that the universe might have a preferred axis, contradicting the assumption that the cosmos is isotropic. The surprising alignment of galaxies on a large scale hints at unknown forces or structures shaping the universe. If true, this could support the idea that our universe is not an isolated system but is influenced by a larger framework, possibly the structure of a black hole’s interior.

Some theories also suggest that black holes could generate new universes through a process called a “big bounce,” where extreme torsion at high densities prevents a singularity from forming. Instead of collapsing to an infinitely small point, matter could rebound, triggering expansion. If our universe formed in such a way, it could explain why physical constants seem fine-tuned for life—because only stable, self-sustaining black hole universes would persist.

This docu-series covers all three of Earth’s next landing options – Asteroids, the Moon and Mars. The programmes explore the scientific reasons for and against each celestial body’s case to be the next that humans might colonise. They explore the technical and logistical problems and benefits of each – EG temperature at night and day, ability or inability to harness solar power and more.

Join the Spark Channel Membership to get access to perks:

/ @sparkdocs.

Watch the best history documentaries, with 50% off your first 3 months, on History Hit: https://historyhit.com/subscribe Using the code SPARK

Find us on:

Facebook: / sparkdocs.

Instagram: / spark_channel.

Any queries, please contact us at: [email protected].