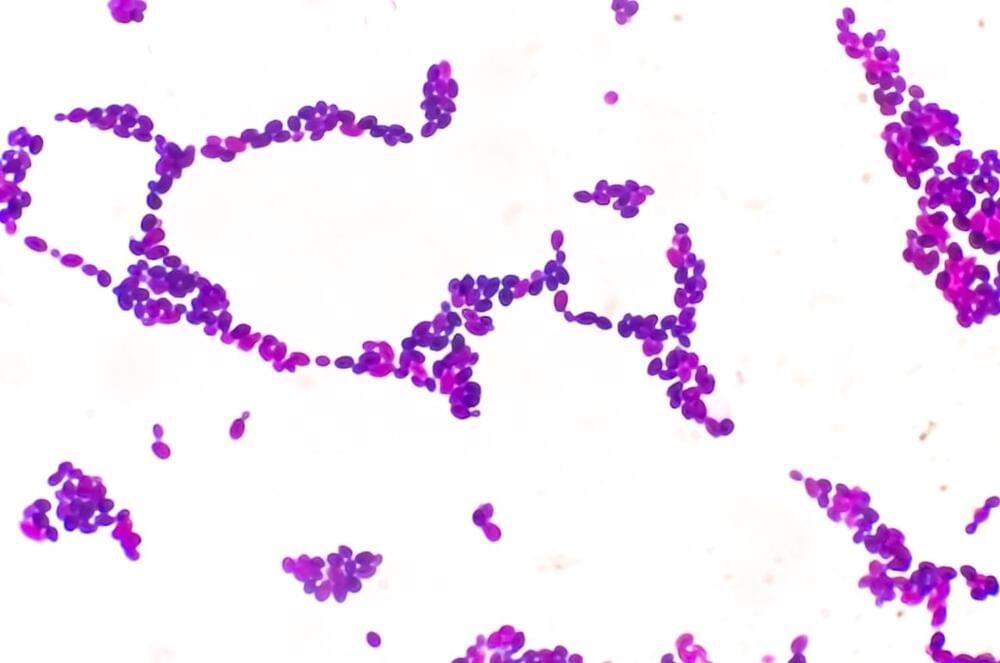

A new study published in Ecology and Evolution by Henrik Svensmark of DTU Space has shown that the explosion of stars, also known as supernovae, has greatly impacted the diversity of marine life over the past 500 million years.

The fossil record has been extensively studied, revealing significant variations in the diversity of life forms throughout geological history. A fundamental question in evolutionary biology is identifying the processes responsible for these fluctuations.

The new research uncovers a surprising finding: the fluctuation in the number of nearby supernovae closely corresponds to changes in biodiversity of marine genera over the last 500 million years. This correlation becomes apparent when the marine diversity curve is adjusted to account for changes in shallow coastal marine regions, which are significant as they provide habitat for most marine life and offer new opportunities for evolution as they expand or shrink. Thus, alterations in available shallow marine regions play a role in shaping biodiversity.