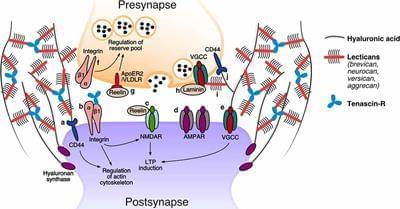

In the adult brain, synapses are tightly enwrapped by lattices of the extracellular matrix that consist of extremely long-lived molecules. These lattices are deemed to stabilize synapses, restrict the reorganization of their transmission machinery, and prevent them from undergoing structural or morphological changes. At the same time, they are expected to retain some degree of flexibility to permit occasional events of synaptic plasticity. The recent understanding that structural changes to synapses are significantly more frequent than previously assumed (occurring even on a timescale of minutes) has called for a mechanism that allows continual and energy-efficient remodeling of the extracellular matrix (ECM) at synapses. Here, we review recent evidence for such a process based on the constitutive recycling of synaptic ECM molecules. We discuss the key characteristics of this mechanism, focusing on its roles in mediating synaptic transmission and plasticity, and speculate on additional potential functions in neuronal signaling.

An increasing number of studies are showing that synaptic function is strongly influenced by their local environment, including the molecules or cellular components in their vicinity. As a result, the classical synaptic framework (consisting of the pre-and postsynaptic compartments only) has gradually been extended to include the neighboring astrocytic processes (the “tripartite synapse”; Araque et al., 1999) and, ultimately, also the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM; the “tetrapartite synapse”; Dityatev et al., 2006). Nowadays, the synaptic ECM is recognized to play an essential role in physiological synaptic transmission as well as in plasticity, and its dysregulation has been linked to synaptopathies in a wide variety of brain disorders (Bonneh-Barkay and Wiley, 2009; Pantazopoulos and Berretta, 2016; Ferrer-Ferrer and Dityatev, 2018).