Pharmaceutical synthesis is often quite complex; simplifications are needed to speed up the initial phase of drug development and lower the cost of generic production. Now, in a study recently published in Science, researchers from Osaka University have discovered a chemical reaction that could transform drug production because of its simplicity and utility.

Pharmaceuticals generally contain a few tens of atoms and a similar number of chemical bonds between the atoms. Thus, designing complex drug architectures from simple precursors using the techniques of organic chemistry usually requires careful planning and tedious, incremental steps.

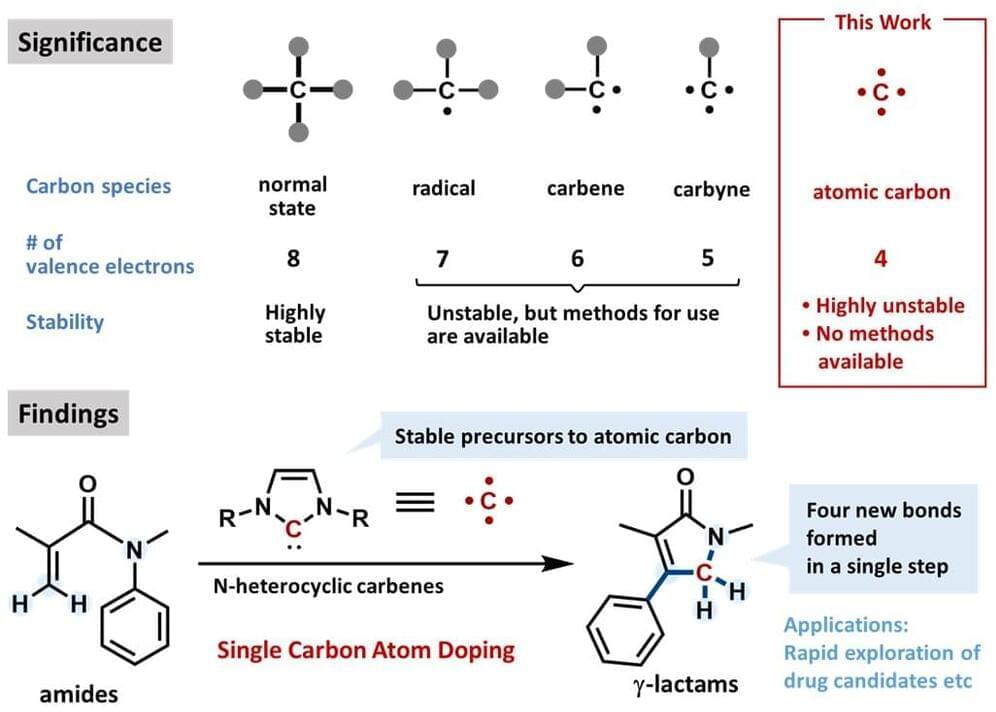

The gold standard in drug synthesis is to create, in one step, as many chemical bonds as possible. In principle, adding one carbon atom—by forming four bonds in one step—to a drug precursor can be a means of doing so. Unfortunately, atomic carbon is generally too unstable for use in common chemical reaction conditions. This is the problem that the researchers sought to address.