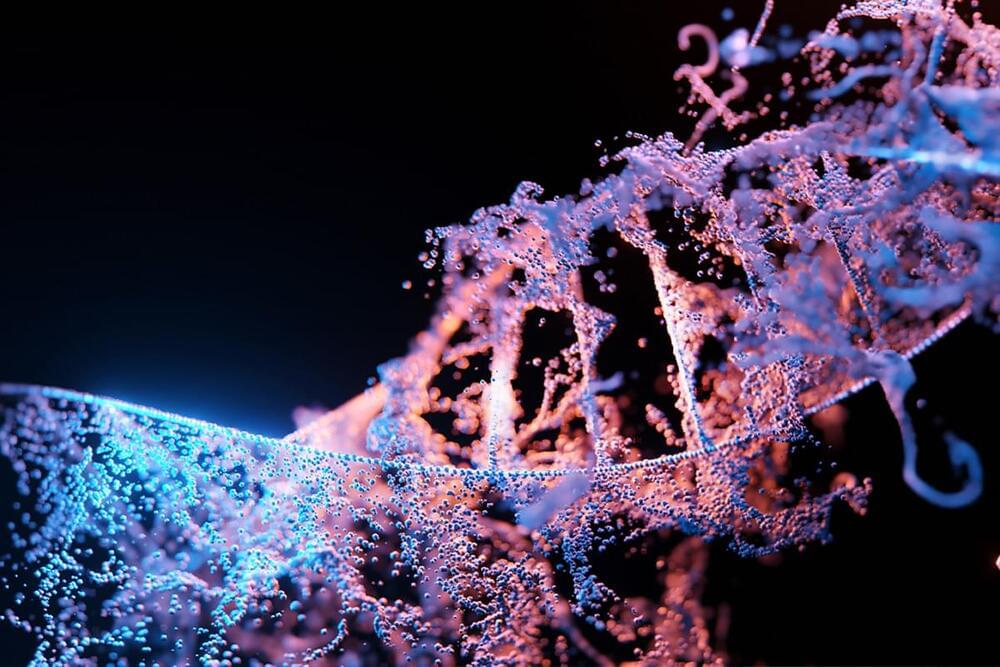

PRESS RELEASE — There has been a lot of buzz about quantum computers and for good reason. The futuristic computers are designed to mimic what happens in nature at microscopic scales, which means they have the power to better understand the quantum realm and speed up the discovery of new materials, including pharmaceuticals, environmentally friendly chemicals, and more. However, experts say viable quantum computers are still a decade away or more. What are researchers to do in the meantime?

A new Caltech-led study in the journal Science describes how machine learning tools, run on classical computers, can be used to make predictions about quantum systems and thus help researchers solve some of the trickiest physics and chemistry problems. While this notion has been shown experimentally before, the new report is the first to mathematically prove that the method works.

“Quantum computers are ideal for many types of physics and materials science problems,” says lead author Hsin-Yuan (Robert) Huang, a graduate student working with John Preskill, the Richard P. Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics and the Allen V. C. Davis and Lenabelle Davis Leadership Chair of the Institute for Quantum Science and Technology (IQIM). “But we aren’t quite there yet and have been surprised to learn that classical machine learning methods can be used in the meantime. Ultimately, this paper is about showing what humans can learn about the physical world.”