The project was the result of a collaboration between NASA and Ohio State University and the new alloy is called GRX-810.

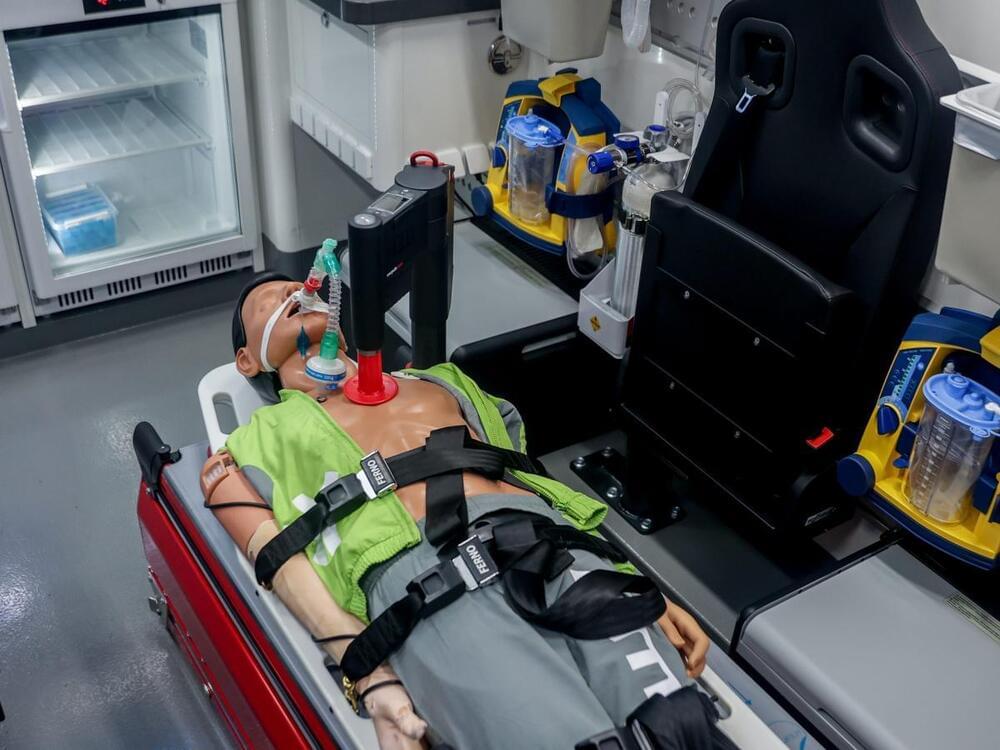

University of Pittsburgh researchers have identified a type of immune cell that drives chronic organ transplant failure in a mouse model of kidney transplantation and uncovered pathways that could be therapeutically targeted to improve patient outcomes. The findings are published in a new Science Immunology paper.

“In solid organ transplantation, such as kidney transplants, one-year outcomes are excellent because we have immunosuppressant drugs that manage the problem of acute rejection,” said co-senior author Fadi Lakkis, M.D., distinguished professor of surgery, professor of immunology and medicine, and scientific director of the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute at Pitt and UPMC.

“But over time, these organs often start to fail because of a slower form of rejection called chronic rejection, and current medications don’t seem to help. Understanding this problem was the motivation behind our study.”

If you’re a fan of life on the high seas, this new project will let you travel them year-round in luxe accommodations.

On Tuesday, private residential ship maker Storylines and Croatian shipyard Brodosplit announced they have signed a ship building contract to create what they’re calling the world’s first environmentally conscious residential ship. The 753-foot vessel, dubbed MV Narrative, has begun its engineering phase. The development’s retail value is estimated at $1.5 billion.

Flying across the world from Europe to Australia currently takes around 20 hours in a regular passenger jet.

But Swiss startup Destinus is looking to slash that time to just four hours — by taking jet travel to hypersonic speeds.

Founded by Russian-born physicist and serial entrepreneur Mikhail Kokorich, Destinus is developing a prototype hydrogen-powered aircraft capable of travelling at Mach 5 and above. That’s five times the speed of sound: over 6,000 kph.

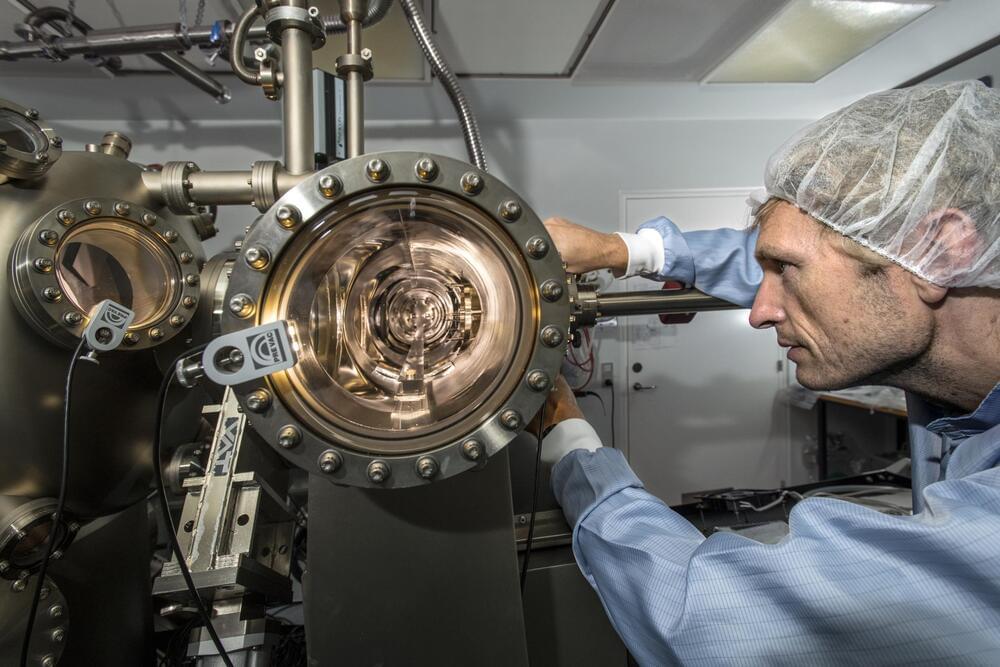

Providing increased resistance to outside interference, topological qubits create a more stable foundation than conventional qubits. This increased stability allows the quantum computer to perform computations that can uncover solutions to some of the world’s toughest problems.

While qubits can be developed in a variety of ways, the topological qubit will be the first of its kind, requiring innovative approaches from design through development. Materials containing the properties needed for this new technology cannot be found in nature—they must be created. Microsoft brought together experts from condensed matter physics, mathematics, and materials science to develop a unique approach producing specialized crystals with the properties needed to make the topological qubit a reality.

Google’s conversation AI tool Bard can now help software developers with programming, including generating code, debugging and code explanation — a new set of skills that were added in response to user demand.

Coding has been one of the top requests Google has received from users, according to a Friday blog post by Google Research product lead Paige Bailey.

Google said Friday it is launching these software development capabilities in more than 20 programming languages including C++, Go, Java, JavaScript, Python and TypeScript. Users can export Python code to Google Colab. Bard can also help with writing functions for Google Sheets.