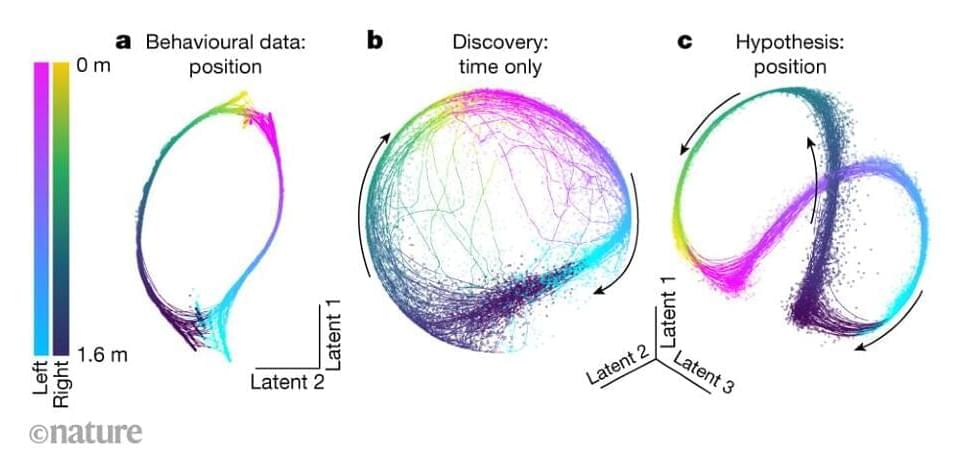

An innovative method decodes and finds hidden relationships in jointly recorded neural and behavioural data.

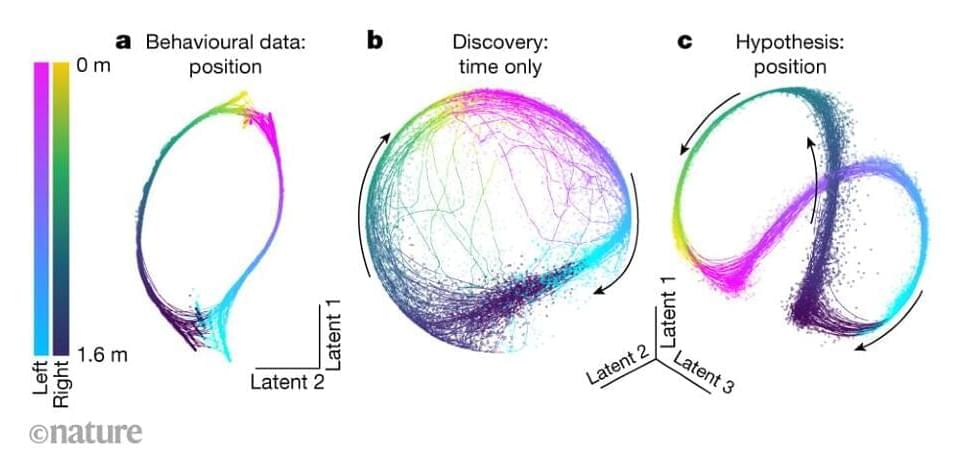

Summary: Researchers proposed the need for a legal framework to guide the conversation on whether or not human brain organoids can be considered people.

Brain organoids are grown from stem cells in a lab, mimicking the growth and structure of real brains. However, they do not fulfill the requirements to be considered natural persons, according to the researchers.

The study explores the potential juridical personhood of human brain organoids, and whether they can be considered legal entities.

Ktsimage/iStock.

So does that mean the internet will also crash by 2026? Well, it won’t if tech companies start using synthetic DNA instead of hard drives to store their data. You may not believe it, but according to Greef and his team, DNA strands can store large amounts of digital data, and in many ways, they have more advantages over modern-day data centers.

Amid all the hype and hysteria about ChatGPT, Bard, and other generative large language models (LLMs), it’s worth taking a step back to look at the gamut of AI algorithms and their uses. After all, many “traditional” machine learning algorithms have been solving important problems for decades—and they’re still going strong. Why should LLMs get all the attention?

Before we dive in, recall that machine learning is a class of methods for automatically creating predictive models from data. Machine learning algorithms are the engines of machine learning, meaning it is the algorithms that turn a data set into a model. Which kind of algorithm works best (supervised, unsupervised, classification, regression, etc.) depends on the kind of problem you’re solving, the computing resources available, and the nature of the data.

In the next section, I’ll briefly survey the different kinds of machine learning and the different kinds of machine learning models. Then I’ll discuss 14 of the most commonly used machine learning and deep learning algorithms, and explain how those algorithms relate to the creation of models for prediction, classification, image processing, language processing, game-playing and robotics, and generative AI.

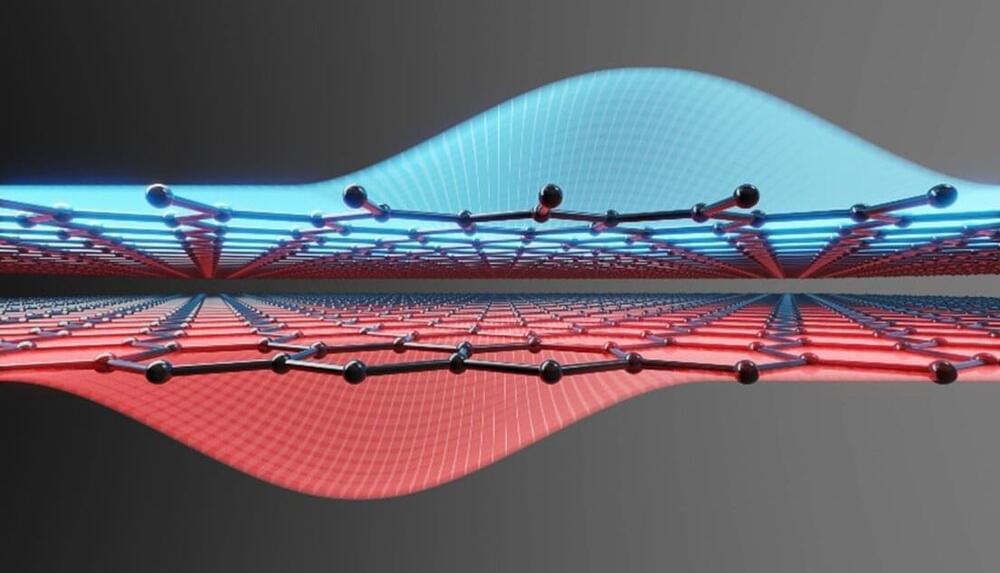

Quantum dots in semiconductors such as silicon or gallium arsenide have long been considered hot candidates for hosting quantum bits in future quantum processors. Scientists at Forschungszentrum Jülich and RWTH Aachen University have now shown that bilayer graphene has even more to offer here than other materials.

The double quantum dots they have created are characterized by a nearly perfect electron-hole-symmetry that allows a robust read-out mechanism—one of the necessary criteria for quantum computing. The results were published in Nature.

The development of robust semiconductor spin qubits could help the realization of large-scale quantum computers in the future. However, current quantum dot based qubit systems are still in their infancy. In 2022, researchers at QuTech in the Netherlands were able to create 6 silicon-based spin qubits for the first time. With graphene, there is still a long way to go. The material, which was first isolated in 2004, is highly attractive to many scientists. But the realization of the first quantum bit has yet to come.

Editor’s note: “Nuclear Power Breakthrough Makes “Limitless” Energy Possible” was previously published in December 2022. It has since been updated to include the most relevant information available.

For a moment, imagine a world of limitless energy – one where energy is so abundant that everyone can power their homes and businesses for mere pennies.

These days, it’s tough to imagine a world like that. Last winter, the average U.S. heating bill was $1,000.

TerraPower, founded by billionaire and Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates in 2008, is opening a new nuclear power plant in Kemmerer, Wyoming. The plant will be the first of its kind, with the company hoping to revolutionize the nuclear energy industry in the U.S. to help fight climate change and support American energy independence.

“Nuclear energy, if we do it right, will help us solve our climate goals,” Gates told ABC News. “That is, get rid of the greenhouse gas emissions without making the electricity system far more expensive or less reliable.”

Gates met with ABC News’ chief business, economics, and technology correspondent Rebecca Jarvis in Kemmerer to talk about the project.