Talk kindly contributed by Michael Levin in SEMF’s 2022 Spacious Spatiality.

https://semf.org.es/spatiality.

TALK ABSTRACT

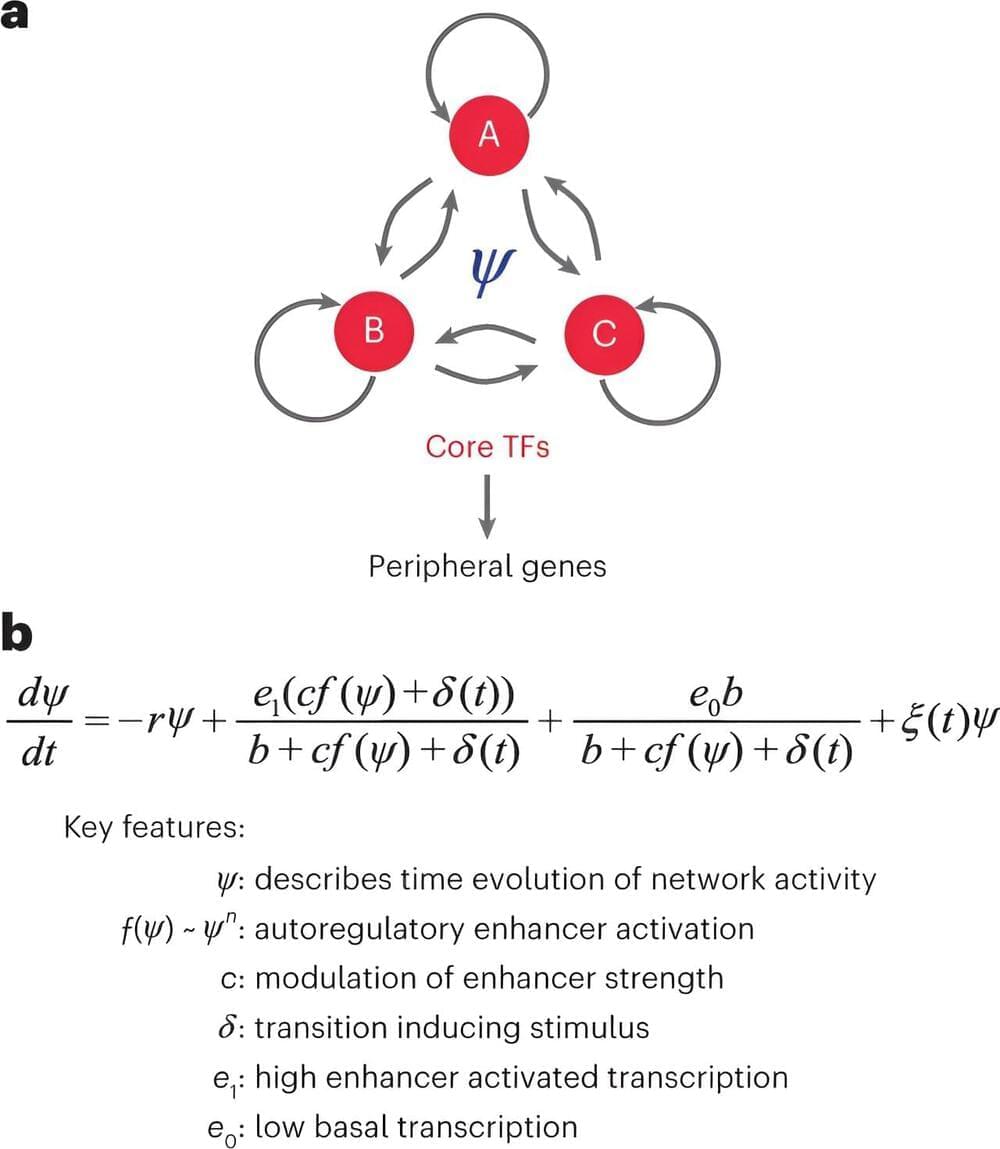

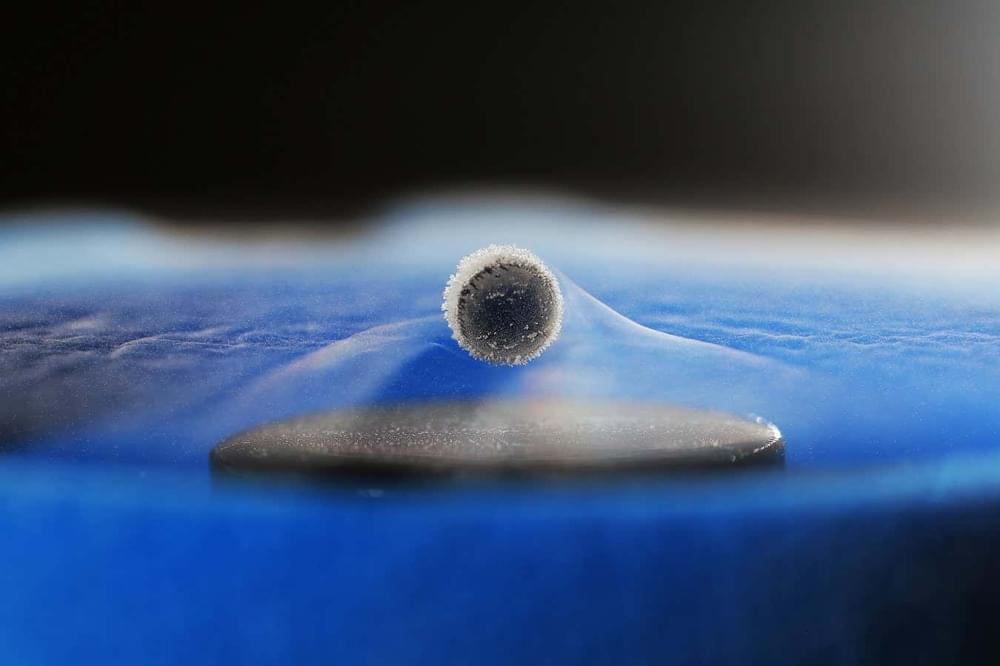

Life was solving problems in metabolic, genetic, physiological, and anatomical spaces long before brains and nervous systems appeared. In this talk, I will describe remarkable capabilities of cell groups as they create, repair, and remodel complex anatomies. Anatomical homeostasis reveals that groups of cells are collective intelligences; their cognitive medium is the same as that of the human mind: electrical signals propagating in cell networks. I will explain non-neural bioelectricity and the tools we use to track the basal cognition of cells and tissues and control their function for applications in regenerative medicine. I will conclude with a discussion of our framework based on evolutionary scaling of intelligence by pivoting conserved mechanisms that allow agents, whether designed or evolved, to navigate complex problem spaces.

TALK MATERIALS

· The Electrical Blueprints that Orchestrate Life (TED Talk): https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_levin_the_electrical_bluep…trate_life.

· Michael Levin’s interviews and presentations: https://ase.tufts.edu/biology/labs/levin/presentations/

· Michael Levin’s publications: https://ase.tufts.edu/biology/labs/levin/publications/

· The Institute for Computationally Designed Organisms (ICDO): https://icdorgs.org/

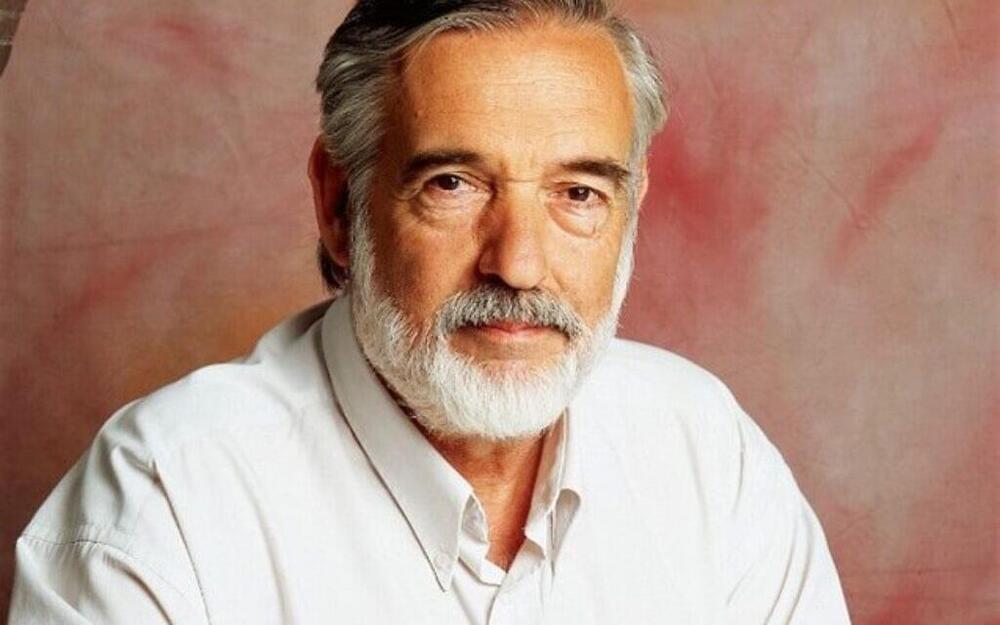

MICHAEL LEVIN

Department of Biology, Tufts University: https://as.tufts.edu/biology.

Tufts University profile: https://ase.tufts.edu/biology/labs/levin/

Wyss Institute profile: https://wyss.harvard.edu/team/associate-faculty/michael-levin-ph-d/

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Levin_(biologist)

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=luouyakAAAAJ

Twitter: https://twitter.com/drmichaellevin.

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/michael-levin-b0983a6/

SEMF NETWORKS